The ruffle gained its popularity in the sixteenth century and was influenced by the Renaissance. Men first wore the ruffles under their doublets and women followed the trend. Soon everyone was wearing ruffles around their collar as a sign of social status and wealth. At first, ruffles were made of linen however, the ruff did not last very long. During this period only, the wealthy could afford to purchase the ruffles which were considered a luxury garments. In fact, it was so expensive that even when the ruffle was purchased it could only be worn a few times due to body heat affecting its shape. The purpose of wearing the ruffled collar besides luxury was to protect the fragile outer fabric of the dress. It was also used to prevent any friction between the skin, neckline, and wrists. The ruffles were also seen as a moral censure.

Later, the ruff was made of starched linen due to the popularity of the use of starch in the mid-1500s. The starch was helpful because the ruff could be worn multiple times and was affordable for everyone. Yellow starch ruffles were also used before women began to dye it various colors such as white, red, blue, and purple. It was known that prostitutes usually only wore a purple ruff. Perhaps, it is why women stopped wearing colored ruffles to prevent from having any confusions. However, the yellow ruff regained its popularity once again in 1615 when a well-known woman wore a banded starched ruffle that was very stiff during her execution.

Queen Elizabeth I influenced the extremely large ruffle during her reign in England in the sixteenth century. The ruffs were incredibly large and were usually made of eighteen or nineteen yards of linen. “He carries his face in’s ruff, as I have seen a serving man carry glasses in a cypress hatband, monstrous steady for fear of breaking” (Stephenson, 371). The ruff collar was so large that some had to be held with wires. Carrying the big ruffs was incredibly difficult and made the simplest task such as eating and drinking difficult to do. Queen Elizabeth however, wore the ruffs closed in the front. Women who had a nice shaped neck preferred to have the ruff opened in the front. The ruff was made of linen but starched stiff with white starch. The ruff could also be made entirely of lace however, it was very expensive. Therefore, lace ruffs were mostly seen only on the Queen and her court. During the Elizabethans period, the ruff continued to be popular, however, later in the Queen’s reign, it was no longer an enormous ruff. The falling band gained popularity and was still made of linen but it was unstarched. The lack of starch made the ruff fall close to the neck. If a falling band was made to reach the edge of the shoulder it would result in being really large. These types of ruffs were decorated with lace usually on the edges. In women, the falling band ruff was made to point downward and opened in the front to show the women’s breast. In men, it was made with a doublet that would be cut I the front and the sides. The falling bands were considered high fashion.

Catherine de Medicis was Italian but married Henry II, the king of France. She was known for introducing the ruff in France. Soon, all women in France followed her trend. Some may say that the queen of France was inspired by Queen Elizabeth’s I ruff collar. However, Catherine de Medicis’ wore a high collar made of small starched ruff. She was also known for wearing a fan-shaped collar made of lace. It was wired at the back to be able to stand upright and feathered out to the sides. This collar was usually worn with a gown that had a décolleté neckline to reveal cleavage. The style of her ruff became popular in France because it was similar to England’s fashion trend. Medicis’ ruff, however, was a bit smaller but still large enough to show sophistication.

Later in the eighteenth century, the ruffles were also worn along with a cravat with matching lace by men. The ruffles were decorated with gold or silver thread and women decorated it with jewels. In 1705, women wore lace ruffles that were made of two or three layers. They were worn under the scalloped sleeves. Even though the ruff was mostly seen on the wealthy, there was a time when working-class people were allowed to wear it too. However, due to its price, not many wore ruffles made of starch linen. Instead, they would create a version of the high-end ruffle by folding small triangles of white muslin. During Louis XVI reign, he made the ruff made of gauze very popular as well. Marie Antoinette was also seen with ruffles on her dress but was not as extravagant as the Elizabethan ruffle. By the end of the nineteenth century, the use of the ruff began to fade and by the twentieth century, the ruff was no longer popular.

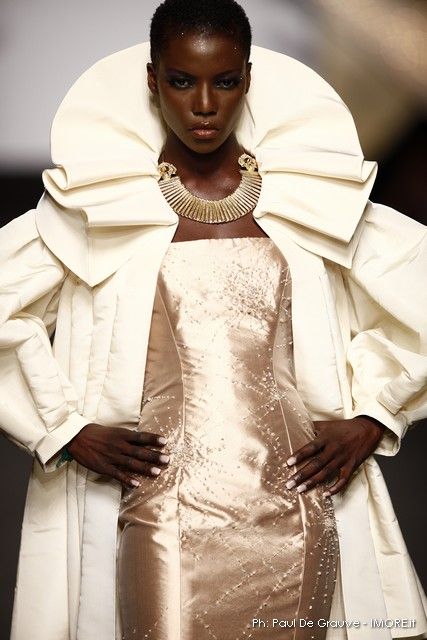

Today, models are walking down the runway with a ruff collar inspired by the sixteenth century. Many fashion designers such as Lulu et Gigi, Junya Watanabe, and Gattinoni are still inspired by Queen Elizabeth’s look. The runway is not the only place where we see the ruff, we also see ruffles in modern dresses, blouses, and skirts. They may not be as extravagant as Queen Elizabeth’s ruff or Queen Medicis’ but it still holds popularity. The meaning of the ruff is no longer the same. It is not worn by the members of the court or symbolizes wealth, however, it still symbolizes classiness and sophistication. Whether the ruff was worn in the sixteenth century or the twenty-first century, the ruff collar is very elegant and makes the whole style look complete.

Bibliography

Delpierre, Madeleine. Dress in France in the eighteenth century. Yale University Press, 1998.

Koda, Harold, and Harold Koda. Extreme beauty: the body transformed. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2012.

Stephenson, Henry Thew. Elizabethan people. Nabu Press, 2010.

Xxxxx. “Ruffs.” The Fashion Historian, http://www.thefashionhistorian.com/2011/11/ruffs.html.