Click HERE for a PDF of this essay, to be reproduced and freely distributed at will.

“It is the responsibility of the student to exceed his teacher. In this way we strive not just to know what our teachers have known but to pursue what they have pursued.” – Bruce Sims

Preface

It is well known in the martial arts community that the history of contemporary Korean martial practice is convoluted and fraught with inaccuracies and misinformation. Discussion on the topic, unfortunately, often breaks down to little more than bickering among followers of the different dogmas. This environment has arisen due to a number of factors, not the least of which are inflated senses of ethnocentrism, political prejudice, and commercial competition. This article is being approached from my personal standpoint as an active practitioner of contemporary Korean martial arts. Every effort has been made to treat all varying historical accounts with scholarly objectivity. Discerning readers and researchers are encouraged to approach this information with a fair degree of scrutiny, and to engage in their own independent research.

At the present time, there are a myriad of perspectives as to the exact origins of Kuk Sool Won™, many of which are pseudo-historical at best. This article represents my personal attempt to consolidate these perspectives into a coherent account of the stylistic roots of the art. The intention of this article is not a defense of any martial style, nor is it meant as propagandistic prose. The text that follows is meant to aide other practitioners in their own martial journey, and to propagate the continued inter-disciplinary exchange of martial ideas.

Introduction

Korea’s historical and on-going role in the cultural exchange of the East is well documented. Many aspects of Korean culture are derived from its neighbors, Japan and China, just as many elements of Korean culture have been assimilated by the Chinese and Japanese. This sort of exchange can be seen in the martial arts, particularly in the many styles of Korean Hapkido and Kuk Sool currently being taught worldwide. As one might expect, then, Korean martial arts are comprised of martial techniques from a wide and varying range of historical sources. This article will discuss the historical arts of which contemporary Hapkido is comprised, and will trace the progression of these arts to the point of their culmination.

Portions of the following text have been abridged for the sake of length, and the sections below are in no way a comprehensive discussion of the various styles. Readers are encouraged to research each style individually for a clearer and more complete picture of each.

For clarity, styles will be discussed in chronological order.

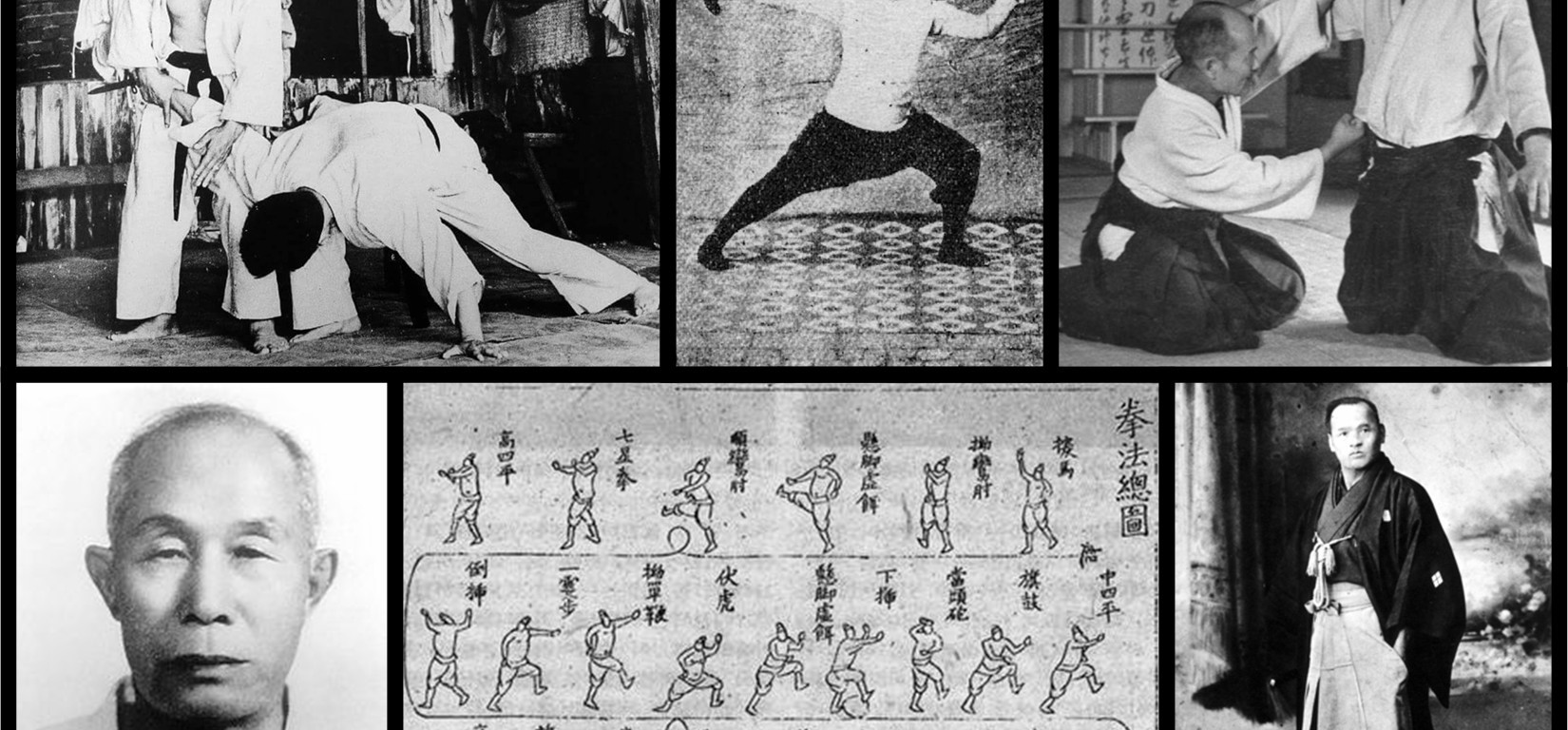

Taekkyon (c. 7th Century)

Though accounts vary as to the exact date and location for Taekkyon’s appearance in Korea, it is most likely that the art developed sometime during Korea’s politically turbulent Three Kingdom Period (57 BC – 668 AD). A number of sources concur that Taekkyon was utilized in battle by the Hwarang warriors of the kingdom of Silla as a response to military threats from the rival kingdoms of Goguryeo and Baekje. During periods of relative peace, Taekkyon was adapted by the non-military population as a sort of competitive event; it is for this reason that it is often referred to as one Korea’s “folk” martial arts, along with Ssireum (a wrestling art similar to Japanese sumo).

Although practice of this authentic Korean style was prohibited during the Japanese occupation, several prominent Korean martial arts historians have made significant progress in the past 50 years in reviving the art. Taekkyon is known for its complex footwork, powerful kicks, and low, fluid stances; it is often attributed as being the parent style of all Korean empty hand forms, in particular dynamic kicking techniques of Tae Kwon Do.

Kung Jung Mu Sool (c. 7th Century)

Sometime during Korea’s Silla period (57 B.C – A.D. 935), young members of the Korean royal family developed a fraternal order of aristocratic youths dedicated to the study and practice of various elements of warfare and politics; the name adopted by the group was Hwarang, or “Flowering Men”. Over the course of several centuries, the Hwarang grew to include civilian members, giving rise to Hwarang-do. As the martial emphasis of the group developed, techniques similar to those of the Japanese samurai became the primary area of study. Eventually, sections of the Hwarang-do developed into an organized group of body guards and personal armies in service of the royal families and members of the royal court. Kung Jung Mu Sool is a blanket term used to denote the martial techniques utilized by the Korean royal court, in particular those techniques of the Hwarang-doi. The skills utilized by these groups included a variety of empty-hand techniques similar to those of Jujutsu and the samurai, as well at the use of various weapons such as the sword, spear, dagger, and collapsing fan. These techniques are thought to have been the foundation for the Muye Dobo Tongji, a martial arts manual produced between the 16th and 18th Century.

Jujutsu (c. 13th – 14th Century)

As the various kingdoms of Feudal Japan began to coalesce at the end of the 12th Century, the need for effective battlefield tactics became more and more paramount. Included in these tactics were techniques of hand to hand combat, both from armed and unarmed positions. The incorporation of battlefield armor negated the ability to use striking or kicking an opponent to defeat or incapacitate them; this necessitated the need for grappling and throwing techniques that would be effective against an armored opponent. Appearing as early as the 1300’s, the unarmed “soft arts”ii of Jujutsu were developed as part of the tactical training of Japan’s samurai and were designed to meet this need. These systems became highly developed during the Tokugawa Period (1600-1868) as a response to the neo-Confucianist principles forbidding warfare, specifically those that forbade taking the life of another. During this time, the term did not denote a specific martial system; rather, it was used as a blanket description for multiple styles of combat.

Mantis Kung Fu (c. 14th – 15th Century)

Though there exist a number of legends as to its origins, Mantis Kung Fu is believed to have been developed during the Northern Song dynasty (960-1127) by the monk, Wang Lang. In the Confucianist tradition, Wang Lang was well educated in a variety of areas, including the martial sciences. Most legends state that Wang, after suffering a number of defeats by a particular monk, went in search of the techniques he would need to overcome his opponent. His search lead to the observation of a duel between a mantis and a cicada in which Wang witnessed the mantis easily overcome a cicada, an insect over twice its own size. Afterward, he spent a period of time studying the movements of the praying mantis, teasing and fighting the mantis with straw and sticks. Wang then developed methods of attack and defense based on the quick and powerful movements of the mantis.

He further developed his style by assimilating the techniques he developed with what he felt were the most effective boxing, kicking, and footwork techniques of the various schools of kung fu. The style that Wang Lang taught incorporated a combination of “hard” striking techniques and “soft” entangling and wrapping techniques. This style relies heavily on deflection and redirection of an attack using circular motions; typically, these deflections are followed immediately by a strike an opponent’s vital areas. Today the style is easily recognized by the signature “mantis fist” hand technique that is prevalent in many of the style’s motions.

Sip Pal Giiii (c. 1700’s)

At the time of this writing, there is significant debate about the meaning of the term Sip Pal Gi. Regardless of which definition of the term is adhered to, nearly all sources agree that the term is used, broadly, to denote martial styles being practiced in Korea that exhibit a strong Chinese influence.

As it will be discussed here, Sip Pal Gi refers to a set of 18 fighting techniques found in the Muye Dobo Tongji. This document, whose title translates to mean “Complete Illustrated Manual of Martial Arts”, outlines techniques for combat using a variety of weaponry including the long staff, spear, various types of swords, flail, and shield. Additionally, the text includes methods of unarmed fighting known as Kwonbeop (or Gwonbeop), as well as techniques for using weaponry from mounted horseback. The work was compiled under the guidance of the Korean Crown Prince Sado (1735-1762) and was intended as a field manual for the Korean army.

Daito-Ryu Akijujutsu (c. 1900)

Originally founded by Takeda Sokaku (1859- 1943), this art represents the grappling, throwing, and joint locking techniques practiced by the pre-Tokugawa samurai. Takeda began training with his father at a young age, and was well versed in several weapon-based styles including kenjutsu (art of the sword) and bojutsu (art of the long staff). After the death of his brother and a failed attempt at priesthood, Takeda traveled to various dojos in Japan and began accumulating a variety of techniques and approaches for both armed and unarmed combat. Beginning in the early part of the 20th Century, Takeda began hosting martial arts seminars in various locations throughout Japan. The techniques of the contemporary Daito-ryu syllabus reflect a direct linage to Takeda’s original teachings.

Yawara/Hapkido (1945)

In the early part of the Japanese occupation of Korea (1910-1945), the young Korean Choi Yong-sul (1904 – 1986) immigrated to Japan. The circumstances of his departure from Korea are somewhat unclear, and accounts vary widely regarding his specific activities in Japan. According to Choi, he served as a house servant and private student of Takeda Sokaku; at the time of this writing, there is little documented evidence to corroborate this claim. Some have postulated that Choi was actually taught by one of Takeda’s students, but this speculative at best. What can be stated with certainty is that when Choi returned to a recently liberated Korea in 1945, he was an adept martial artist with skills taken directly from Takeda’s Akijujutsu.

Choi began teaching his style privately upon his return to Korea, and opened his first public school sometime in the early 1950’s. Choi’s style relied heavily on the techniques of Aikijujutsu, but also incorporated techniques of various other styles such as karate (Kr. kong soo do) and judo (Kr. yudo). Initially, Choi made no attempt to mask the fact that he trained in the Japanese style Daito-Ryu Aikijujutsu (often pronounced Dae Dong Ryu Yu Sool or Dae Dong Ryu Yawara in Korean), referring to his style simply as Yawara. The name Hapkido appeared around 1958, when Ji Han Jae, along with some of Choi’s other students, incorporated the kicking techniques of Korean Taekkyon and created a unified syllabus of training material and techniques.

The syllabus defined by Choi and his successors has served as the basis for a host of contemporary styles of Korean combat which refer to themselves using the designation “hapki” (synonymous with the Japanese term Aiki). These include Hapkido, Hapki-yusul, Sin Moo Hapkido, Kuk Sool Won, Kuk Sool Do, and a variety of others. In the modern context, the term hapkido refers not to a specific martial style, but to a set of principles on which many styles are formed.

Conclusion

Korea’s rich cultural history, including the history of its martial systems, has always exerted a reciprocal influence on the cultures of its neighbors. Kuk Sool Won™ occupies a prominent position within the scope of this exchange. The various styles which have influenced the development of Kuk Sool Won™ afford practitioners of the art a unique perspective into the history and development of martial arts. In seeking an understanding of our current practice, it is always pertinent to develop an understanding of the arts from which we derive our roots. As martial artists, and as citizens of humanity, it is important to remember that an understanding of who we are begins with an understanding of who we were.

©2016 Joshua G. Floyd

i. Both “Kung Jung Mu Sool” and “Hwarang-do” are used contemporarily to denote specific martial styles as founded by Soon Tae Yang and Dr. Joo Bang Lee, respectively. This article, however, deals with the terms as they appear in the historical context of Korean martial arts.

ii. It is important to note that the idea of a “soft art” today is far different than it would have been for the samurai. Typically, contemporary “soft” arts focus on incapacitation of an opponent through pain induced submission rather than by killing. The “soft” techniques of the samurai, however, were far more brutal than those of contemporary arts such as Judo and Aikido, and were typically used to disarm and immobilize an opponent before killing them.

iii. In contemporary martial arts, the designation Sip Pal Gi (or Ship pal gi, ship pal ki, etc.) is often seen as referring to “Korean kung fu.” While it is almost certain that monks and martial artists from China spent time in Korea at various points throughout history and undoubtedly taught their skills, kung fu is an inherently Chinese art. It is the opinion of the author that the designation of “Korean kung fu” is historically misleading, especially when labeled under the banner of Sip Pal Gi.

References & Further Reading:

Note: Not all of the sites listed below should be considered as scholarly sources. Readers

are advised to treat these links with scrutiny.

Allmartialarts.com. “Lineage of the Korean Martial Arts.” http://www.allmartialarts.com/KIXCO/History/history/map.htm.

Black Belt Magazine Online. “Korean Martial Arts History.” http://www.blackbeltmag.com/category/korean-martial-arts-history/.

Bloody Elbow. “Jiu-Jitsu History: Birth on the Battlefield.” http://www.bloodyelbow.com/2011/10/13/2481689/jiu-jitsu-history-birth-on-the-battlefield.

Encyclopedia Britannica Online. “Tokugawa period.” http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/598326/Tokugawa-period

Fighting Arts. “Ask the Teacher – Topic: Ship Pal Gi.” http://www.fightingarts.com/reading/article.php?id=268.

Kuk Sool Mu Ye. “Ancient History.” http://www.ksmymartialarts.com/html/html_ver/text_section.php?curr_page=1&sec_id=8&multi_id=3.

Level 10 Kung Fu “Korean Kung Fu (Sip Pal Gi).” http://www.ltkfa.com/index.cfm?page=15.

International Sever-Star Mantis Style, Lee Kam Wing Martial Art Association. “History of the Seven Star Praying Mantis Style.” http://www.brianwinterdesign.com/LKW/history.html.

“History of Taekkyon.” Korea Taekkyon Federation. http://www.taekkyon.or.kr/en/

Martialartsblogaroundtheworld. “Subak and Taekkyeon: Before It Was Called Taekwondo.” http://martialartsblogaroundtheworld.wordpress.com/2012/04/23/subak-and-taekkyeon/.

Martialartsblogaroundtheworld. “Taekkyeon: The art that still lives.” http://martialartsblogaroundtheworld.wordpress.com/2012/04/24/taekkyeon/.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Silla: Korea’s Golden Kingdom.” http://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2013/koreas-golden-kingdom/

North Austin Tae Kwon Do. “History of the Hwarang, Korea’s Warrior Knights.” http://www.natkd.com/legend_of_the_hwarung.htm.

Praying Mantis Kung Fu Academy. “History of Praying Mantis Kung.” http://martialartsblogaroundtheworld.wordpress.com/2012/04/24/taekkyeon/.

Ushistory.org. “10c. Feudal Japan: The Age of the Warrior.” http://www.ushistory.org/civ/10c.asp.

World Hwa Rang Do Association. “Hwa Rang Do History.”http://hwarangdo.com/hrd-history/hwa-rang-do-history/.

Wikipedia. “Jujutsu – Origins.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jujutsu#Origins.

Wikipedia. “Northern Praying Mantis (martial art).” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Northern_Praying_Mantis_(martial_art)

World Heritage Encyclopedia Online. “Sibpalgi.” http://worldheritage.org/articles/Sibpalgi

Cyrus, Ian. “History of Hapkido.” International Korean Martial Arts Federation. http://www.ikmaf.com/index.php/styles/yu-shin-hapkido/history-of-hapkido.

Eisenhar, Darwin J. “Kung Jung Mu Sool.” taekwondo-training.com. http://www.taekwondo-training.com/education/kung-jung-mu-sul.

Funk, Jon. “Praying Mantis Kung Fu: Forms History.” 7 Star Praying Mantis Kung Fu. http://www.mantiskungfu.com/praying_mantis_kung_fu_forms_history.php.

Jung, Hyung Min. “Hwa Rang Do Founder Joo Bang Lee on the History of Korean Martial Arts.” Black Belt Magazine Online, 2011. http://www.blackbeltmag.com/daily/traditional-martial-arts-training/hapkido/hwa-rang-do-founder-joo-bang-lee-on-the-history-of-korean-martial-arts/.

Pranin, Stanley. “Chronology of Sokaku Takeda.” Aikido Journal (blog). http://blog.aikidojournal.com/2011/08/19/chronology-of-sokaku-takeda-by-stanley-pranin/.

Pranin, Stanley. “Jujutsu and Taijutsu.” Aikido Journal #103 (1995). http://www.aikidojournal.com/article.php?articleID=17.

Pranin, Stanley. “Choi, Yong Sul.” Encyclopedia of Aikido. https://www.aikidojournal.com/encyclopedia?entryID=119

Sattler, Michael “Hapkido: What Is Hapkido?” Accessed June, 2014. http://www.sattlers.org/mickey/hapkido/foreigners/whatIsHapkido.html.

Sims, Bruce. “Sip Pal Gi.” Forum post. Martial Arts Planet. http://www.martialartsplanet.com/forums/showthread.php?t=78150&page=2