Portuguese dictator António de Oliveira Salazar is a bloated sac, a sort of human bagpipe, vomiting and shitting through a long tube coming out of his arse. Unless it is a mouth, down there in the bottom left-hand corner of Paula Rego’s painting from 1960. There’s another figure in the middle, like a rotten mango with pubes and what looks like a giant, hairy testicle. I think it is supposed to be a woman. Salazar Vomiting the Homeland, the earliest painting in Rego’s show at the new Milton Keynes Gallery, is but the first in a room filled with angry, dirty, nasty paintings made as a response to the repression and mediocrity of living under Salazar’s regime.

Sometimes the titles are as telling as the works. “When we had a house in the country we’d throw marvellous parties and then we’d go out and shoot negroes” refers to the excesses of the colonial rule and wars in Angola. Maybe the phrase was one Rego had heard, or one she invented. Throughout her career, she has drawn on her own life, becoming a storyteller and chronicler in paint and pastel, in the etching needle and in words. There is an intimate 2017 documentary by Rego’s film-maker son, Nick Willing, available on BBC iPlayer, to coincide with the opening of this exhibition. Using interviews, home movies and archive footage, it shows the intimate connections between Rego’s art and life. She has invented them both.

Ferocious and tender, her pictures – as she often calls them – are filled with coded messages, some more easily read than others. Like children’s stories with adult themes, there are jealousies and affairs, adulteries and betrayals, longings and losses, ambivalences. Born into a middle-class Portuguese family in 1935, Rego was sent to a finishing school in England and then attended the Slade in London, run by the patrician William Coldstream. Much emphasis was placed on the plumb lines and measurements, the subdued palette and continual visual reassessments and supposed objectivity of the Euston Road school of drawing. Visiting tutors such as Lucian Freud and LS Lowry provided light relief. Rego escaped into a kind of narrative, loose pictorial style bordering on caricature.

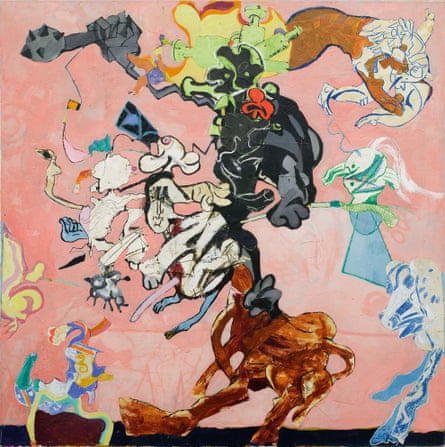

There was also, she has said, a lot of shagging. Becoming pregnant by her tutor Victor Willing, she returned to Portugal to have the first of three children with him before returning to London to complete her studies. Rego’s paintings in the 1960s became like collapsed storyboards, whose elements and characters were drawn and painted as cut-out forms, a bestiary of figures, mangled beings, personages that looked as though they had escaped from medieval manuscripts, that were moved around the canvas and glued on. There are flashes of Picasso, cartoonish creatures, biomorphic blunders, riffs on Joan Miró, silhouettes of her left-leaning, anticlerical father and exiled grandfather, and, in one painting, a reference to an Italian woman with whom Willing was having an affair. Somehow she kept all these elements airborne, in a kind of weightless jumble.

Politics were in there, too – from the assassination of the Portuguese king and his son in their carriage in 1908 (conflated with the shooting of John F Kennedy in an open car in 1963), as well as more recent events in Portugal and under Francisco Franco’s regime in Spain. Surprisingly, many of these works were shown without censure in Portugal. Perhaps it was considered politic to ignore them.

As Rego progressed, Willing’s own art faltered and stalled. He was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 1967, and she became his carer, with all the contradictions, love, frustration and anger that entailed. She painted it all.

Curated by Catherine Lampert, the Milton Keynes show jumps decades and, while missing some key works, picks out the major themes and modes in Rego’s art. It is an exhilarating, at times alarming ride, one that is thought-provoking, funny and sometimes desperately painful. In a group of works in which animals act out scenes from a fraught marriage, a monkey offers a bear a poisoned dove; in another, a wife (who unaccountably has a third, withered green leg) cuts off the tail of her monkey husband with a giant pair of shears. He vomits on the floor as the bear looms, cropped by the edge of the image. With their blank grounds and simplified touch, they might be taken as macabre feminist variations on the sort of freewheeling return to figuration current in the early 1980s. What I didn’t see at the time was the way in which Rego was playing out her relationship with Willing (the monkey), and her long-time lover, Rudolf Nassauer (the bear).

A further significant shift in her art took place around 1986. She simplified her work at the end of the 70s, and then complicated it again with jumbles of figures, stories, out-of-scale elements and collisions of styles and degrees of figuration. Through the 80s, the volumes and shadowing and light in her paintings became more modelled, the figures more rounded, the spaces they inhabited more continuous. Stage-like landscapes, fusty domestic rooms (often remembered from childhood), the dressing tables and antimacassars and other accoutrements of an outmoded everyday furnish her painted dramas. Portuguese maids plot to murder their employer (a reference to Jean Genet’splay The Maids); a small, malevolent boar wanders among the shadows. There is an atmosphere of malaise, sexual tension, repression and threatened violence. Props abound – a fearsome garden rake, a claw-hammer and a jug, flowers. The light is also a protagonist. It sees what it sees, and begs us to pay attention. Even when taking us outdoors, the atmosphere is claustrophobic and stuffy. Two girls dress a dog. Another cajoles a pelican. Another pair sleep beside a tree.

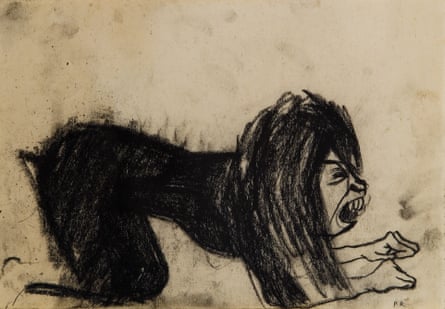

This is where Rego starts to get really interesting, as if she were moving her characters into place, giving them a voice in the stultifying silence. She begins to care about evoking particular dresses, remembered places, things as well as people. She discovered how the most minimal of gestures, a look, a way of sitting or a turn of a head can imply an interior world. To give her characters a sense of having thoughts and inner lives, self-awareness and introspection, she has to re-adopt something like realism, or at least to paint a believable world that can exist in continuum with our own. You could step into it and belong –though the chances are you wouldn’t want to. She starts to use pastel instead of acrylic, drawing herself as a dog, or rather as a woman behaving like a dog, waiting, sitting (alert in her armchair, pregnant), pining, sleeping on her master’s coat, a dog bowl on the floor behind. She begins to use models – including herself and her family. The women always look like Paula anyway. She is in all her characters, male as well as female, masked and unmasked.

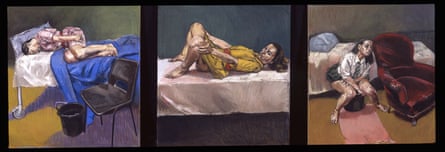

Pastel fuses painting and drawing and also slows down her racing thoughts. Her works now have to be built, layer on layer, colour on colour, contours fusing together. Something of her Slade training returns. She starts using furniture, dolls, masks and other studio props. She paints two girls being stoned, and in 1998, a series of paintings about abortion. A public referendum on the subject failed to attract sufficient votes in Portugal, provoking her to paint a series of young women. They sit on towels, open legged, or squat on an ordinary plastic bucket. There are basins and bowls, traumatised and frightened young women, one with her legs up on camping chairs, as make-dos for a gynaecologist’s stirrups. Showing these paintings in Portugal, as well as a series of etchings on the same subject, undoubtedly influenced a 2007 referendum, which led to the legalisation of abortion, when her images were republished in Portuguese newspapers. A further group of etchings depict scenes of female genital mutilation. These are even more ghastly and awful, not least because of their treatment almost as folkloric images.

The show as much as Rego’s art builds its momentum. Here’s Rego dancing, not once but many times. Here are tragic men and knowing women. The women in her art always know more. Here is repression, here’s freedom, the stupid and the unafraid. Her work is all an exorcism. Life – ours as well as hers – courses through it.

Paula Rego: Obedience and Defiance is at Milton Keynes Gallery, 15 June-22 September.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion