China and the US should be wary of the historical parallels with 1914

- A catalyst setting a rising power and its allies against an entrenched power in a bloody conflict where no one wins? It happened last century in Europe, and could again if Beijing cracks down hard on Hong Kong

The year 2019 is meaningful for China and the world in so many ways. It marks the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China and the 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen uprising.

It is momentous for another, less celebrated, reason: the centennial of the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, formally ending World War I. At the Paris Peace Conference, China demanded the return of Shandong peninsula, which had been surrendered by Germany to Japan. Rejection of China’s demand brought forth the May Fourth Movement, allowing Marxist ideas to take hold.

Japan saw its proposal for a racial equality clause in the treaty stymied, leading to its disillusionment with the international system of the day and rapid militarisation, ultimately causing millions to perish. Germany, of course, regarded the treaty and its prohibitive terms as abject national humiliation.

World War I started as a result of Bosnian Serb nationalist Gavrilo Princip’s assassination of archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian empire, in Sarajevo in 1914, interlocking alliances among European powers, and inept governments who thought any war would be brief and decisive.

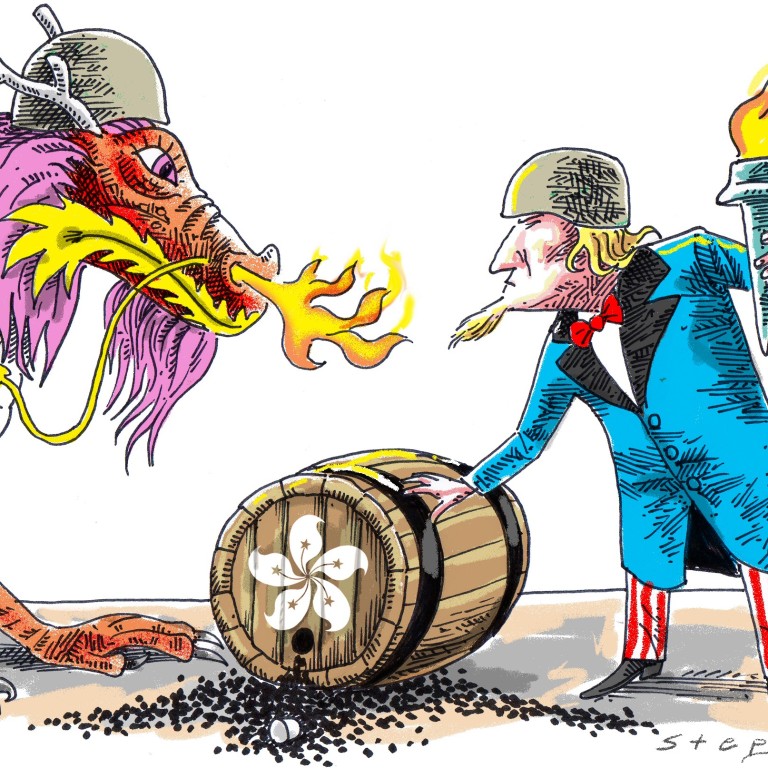

Eerie comparisons can be drawn between events leading to World War I and those surrounding Hong Kong. A murder in another place (Sarajevo; Taiwan) that a rising state (Germany; China) seeks to exploit to augment its power, which other states (Britain, France and Russia; the US) seek to contain.

The issue is then magnified through military alliances. Threats and ultimatums from both sides rapidly escalate.

Ghosts of Occupy return to haunt Hong Kong

The successful subduing of the “umbrella movement” in 2014 led to hubris in Lam, the Hong Kong government and Beijing, emboldening them to believe all their policies, thanks to pro-establishment functional constituencies, would go unhindered.

Having learned from their mistakes since 2014, protesters this time have garnered greater general support in Hong Kong and refuse to relent on their five demands, lest the government do what it did five years ago. Lam’s calls for dialogue, which she rejected when the furore over the extradition bill was in its infancy and salvageable, now fall on deaf ears.

As October 1, China’s National Day, rapidly approaches, resolution of the Hong Kong crisis becomes increasingly critical. Protesters, and the Hong Kong and central governments, know time is running out, yet neither side is conceding.

How the 2019 Hong Kong protests compare with the 1967 riots

Beijing’s grand national objective of reuniting China with Taiwan, for which Deng Xiaoping intended Hong Kong’s “one country, two systems” formula to be a blueprint, has already been scuppered. Its support for the extradition bill and responses to the Hong Kong protests have exposed the fragility of the formula.

It is not beyond the realm of plausibility that Xi might decide that a display of sheer force to suppress the protests in Hong Kong is the only way to deter Taiwan from declaring independence. In addition to seeking to discredit protesters in Hong Kong, Beijing’s disinformation campaign on social media is arguably paving the way for intervention by force.

A Tiananmen-style crackdown would be catastrophic for China

A “Tiananmen 2.0” will irretrievably alienate Hongkongers from China, bringing about the unnatural death of the “one country, two systems” formula and of the Hong Kong the world knows. It will set China, Hong Kong, Taiwan and the United States on a dangerous trajectory.

A military conflict between the two superpowers will spare neither their allies, nor neutral states.

And no one in 1914 had the foresight to realise that a murder in Sarajevo would result in a general war within a month, and the collapse of the German, Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman and Russian empires within four years.

As “those who do not learn history are doomed to repeat it”, Beijing and Washington must be rational in their actions regarding the powder keg that is Hong Kong.

Born and raised in Hong Kong, Phil C.W. Chan is senior fellow at the Institute for Security and Development Policy. He is author of the book China, State Sovereignty and International Legal Order. Niklas Swanström is executive director of the Institute for Security and Development Policy. His expertise lies in conflict prevention, conflict management and regional cooperation