Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

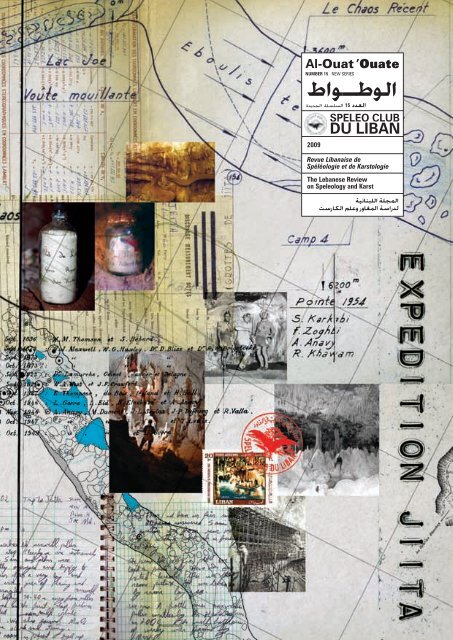

<strong>Al</strong>-Ouat ’Ouate<br />

NUMBER 15 NEW SERIES<br />

طاوـطولا<br />

ةديدجلا ةلسلسلا 15 ددعلا<br />

2009<br />

SPELEO CLUB<br />

DU LIBAN<br />

Revue <strong>Liban</strong>aise de<br />

<strong>Spéléo</strong>logie et de Karstologie<br />

The Lebanese Review<br />

on Speleology and Karst<br />

ةينانبللا ةلجملا<br />

تسراكلا ملعو رواغملا ةساردل<br />

<strong>Al</strong>-Ouat ’Ouate 15<br />

| 1

2 | <strong>Al</strong>-Ouat ’Ouate 15<br />

| 3

17/1/57 خيرات 90 مقر ربخو ملع 1951 ماع سسأت<br />

28/11/63 خيرات 14262 مقر موسرملا ةماع ةعفنم تاذ ةيعمج<br />

28/11/69 خيرات 512 مقر )طباض( ينطولا زرلاا ماسو لماح<br />

10/10/05 خيرات 154000 مقر )سراف( ينطولا زرلاا ماسو لماح<br />

رواغملا يف بيقنتلل ينانبللا يدانلا<br />

نانبل, سايلطنا 70 923 :ب.ص<br />

<strong>Spéléo</strong> <strong>Club</strong> <strong>du</strong> <strong>Liban</strong><br />

P.O.Box 70 923, Antelias, Lebanon<br />

For more information:<br />

info@speleoliban.org<br />

www.speleoliban.org<br />

ISSN 1999-8287<br />

FONDE EN 1951 AU.MIN.NO. 90 DU 17/1/57<br />

RECONNU D’UTILITE PUBLIQUE DU NO. 14262 DU 28/11/63<br />

CITE A L’ORDRE NATIONAL DU CEDRE (Officier) NO. 512 DU 24/2/69<br />

CITE A L’ORDRE NATIONAL DU CEDRE (Chevalier) NO.15400 DU 10/10/05<br />

يدان مدقأ وه و يبكرك يماسو ماوخ نومير ،يفانأ ريبلا ،ه ّ رغ لانويل دي ىلع رواغملا يف بيقنتلل ينانبللا يدانلا سسأت 1951 يف<br />

ةقلعتملا نوؤشلا يف يدانلا متهي .ملاعلا ءاحنا عيمج يف نيعزوم وضع 200 نم رثكا مضي .طسولاا قرشلا يف نيروغتسملل<br />

يف و )1963/11/28 خيرات 14262 مقر موسرملا( ةماع ةعفنم تاذ ةيعمج بقل قحتسا 1963 يف .ةسراكلا ملع و رواغملاب<br />

زرلاا ماسو لان هنأ امك اتيعج ةراغم يف هلامعا ىلع )1969/2/24 خيرات 512 مقر( طباض ةبترب ينطولا زرلاا ماسو لان 1969<br />

.)2005/1./1. خيرات 154000 مقر( سراف ةبترب ينطولا<br />

The <strong>Spéléo</strong> <strong>Club</strong> <strong>du</strong> <strong>Liban</strong> was founded in 1951 by Lionel Gorra, <strong>Al</strong>bert Anavy, Raymond Khawam and Sami<br />

Karkabi. It is the oldest caving club in the Middle East. It has over 200 members all over the world. The club<br />

specializes in speleology and karst. The club was awarded the 'A <strong>Club</strong> that is a Benefit to the Public' Order by the<br />

Lebanese government in 1963. 'The National Order of the Cedars', from the Lebanese government was awarded<br />

for their work in Jiita Cave, rank Officer, in 1969. In 2005 a second Order of the Cedars was awarded to the<br />

club, rank Knight.<br />

Le <strong>Spéléo</strong> <strong>Club</strong> <strong>du</strong> <strong>Liban</strong> fut fondé en 1951 par Lionel Gorra, <strong>Al</strong>bert Anavy, Raymon Khawam et Sami Karkabi. Il s’agit<br />

<strong>du</strong> plus ancien club de spéléologie au Moyen-Orient et comprend plus de 200 membres au monde entier. Le club est<br />

spécialisé en spéléologie et karstologie. En 1963, il fut décrété d’utilité publique (décret N˚14262 <strong>du</strong> 28/11/1963). En<br />

1969, il reçu l’Ordre National <strong>du</strong> Cèdre <strong>du</strong> grade Officier (N˚512 <strong>du</strong> 24/02/1969) pour les travaux effectués dans la grotte<br />

de Jiita et reçu en 2005, un second Ordre National <strong>du</strong> Cèdre <strong>du</strong> grade Chevalier (N˚154000 <strong>du</strong> 10/10/2005).<br />

<strong>Al</strong>l Rights Reserved<br />

© 2009 SPELEO CLUB DU LIBAN<br />

No part of this publication may be repro<strong>du</strong>ced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy,<br />

recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the copyright owner.<br />

<strong>Al</strong>-Ouat ’Ouate<br />

NUMBER 15 NEW SERIES<br />

طاوـطولا<br />

ةديدجلا ةلسلسلا 15 ددعلا<br />

Revue <strong>Liban</strong>aise de<br />

<strong>Spéléo</strong>logie et de Karstologie<br />

In collaboration with<br />

The Lebanese National Council for Scientific Research<br />

4 | <strong>Al</strong>-Ouat ’Ouate 15 | 5<br />

2009<br />

SPELEO CLUB<br />

DU LIBAN<br />

The Lebanese Review<br />

on Speleology and Karst<br />

ةينانبللا ةلجملا<br />

تسراكلا ملعو رواغملا ةساردل<br />

Editors<br />

Issam Bou Jaoude<br />

Johnny Tawk<br />

Layout and collages<br />

Rena Karanouh

“Learn to see” as physician William Osler said in the 19th century.<br />

What helped scientists like Charles Darwin, <strong>Al</strong>fred Russel, Franklen Evans, Edouard Dupont and<br />

others to understand is that they not only possessed the ability to look but also to see. This is the major<br />

foundation for their amazing discoveries.<br />

Learning to ‘look and see’ is what SCL is trying to do.<br />

Lebanon, the land of karst in the Middle East, has a special ecosystem being a melting point<br />

between Africa, Asia and Europe. It has striking caves and karst elements that not only need to be looked at,<br />

but also to be seen.<br />

In Lebanon we are starting to uncover the amazing karst environment that we live in, including our<br />

remarkable caves, speleothems and fauna present in them. <strong>Al</strong>l this and much more are to be looked at and<br />

seen in such a fragile environment. Caves are truly the last frontiers on earth and in Lebanon and they still hold<br />

places that have never been seen before.<br />

Let us keep our eyes open and watch out for the amazing environment that we live in.<br />

We should also thank and pay tribute to our fathers, who got us were we are now, and in their<br />

honour let us teach and help the new generation to follow the path that we have learnt.<br />

Issam Bou Jaoude<br />

Editor<br />

We would like to thank Shk. Khalid Bin Thani A. <strong>Al</strong> Thani from First International Investment Group,<br />

Mr. Ab<strong>du</strong>lla Bin Nasser <strong>Al</strong> Misnad from Gulf Cement Company and Mr. Marwan Zgheib from MZ & Partners for<br />

their moral and financial support to ensure a consistent release of our publication.<br />

We would also like to thank Dr. Dia Karanouh and Mrs. Nidal Nseir and Ms. Hala Bou Jaoude for<br />

their valuable revision of the English articles, Stephanie Mailhac for her French translation and Maya Sarrouf<br />

for her help.<br />

اهيفلؤم ةيلؤسم يه طاوطولا ةلجم يف تروشنلما اهونيماضمو تلااقلمأ.<br />

The articles and their content published in the <strong>Al</strong> Ouat’Ouate magazine are the responsibility of their authors.<br />

La responsabilité des articles publiés dans <strong>Al</strong> Ouat’Ouate n’engagent que leurs auteurs.<br />

10 LES PREMIERS<br />

20 ROUGE SUR BLANC 24 FINAL NOTES<br />

28<br />

TRAÇAGES À<br />

Maïa Sarrouf<br />

ON SALLE<br />

L’URANINE<br />

BEAYNO<br />

AU LIBAN<br />

Elias Labaki<br />

Sami Karkabi<br />

Samer Harb<br />

34 FIRST GEOCHEMICAL 42 JIITA WITH SAMI<br />

50 STALAGMITES AND 54<br />

STUDY OF<br />

Rena Karanouh<br />

COLUMNS OF JIITA<br />

STALAGMITES<br />

Georges Haddad<br />

FROM JIITA CAVE<br />

Fadi Nader<br />

Issam Bou Jaoude<br />

68 PRELIMINARY<br />

70 BAT CENSUS IN<br />

74 EVALUATION OF<br />

80<br />

ANALYSIS OF THE<br />

LEBANESE CAVES<br />

HUMAN IMPACTS<br />

ARCHAEOLOGICAL<br />

2008 & 2009<br />

ON KANAAN CAVE<br />

MATERIAL<br />

Assad Saif<br />

Ivan Horáček et al<br />

Maïa Sarrouf<br />

85 مادتسلما طئارلخا مسر<br />

Philipp Häuselmann<br />

88 WHAT’S IN A LOGO<br />

Nadine Sinno<br />

94 OUR THURSDAY<br />

MEETING<br />

HEADQUARTERS<br />

Bashir Khoury<br />

96<br />

98 ADVENTURES IN<br />

CAVE CLIMBING<br />

Issam Bou Jaoude<br />

104<br />

IRAN<br />

Johnny Tawk<br />

Habib el Helou<br />

Fadi Nader<br />

108 DISCOVERING ES-<br />

SUWAYDA<br />

LAVA CAVES IN<br />

SOUTHERN SYRIA<br />

Johnny Tawk et al<br />

112<br />

contents<br />

THE SALLE<br />

BLANCHE<br />

EXPEDITION<br />

Issam Bou Jaoude<br />

Wassim Hamdan<br />

LA PHOTOGRAPHIE<br />

SPÉLÉOLOGIQUE<br />

AU LIBAN<br />

Sami Karkabi<br />

Johnny Tawk<br />

RAYMOND KHAWAM<br />

Sami Karkabi<br />

Johnny Tawk<br />

PROTECTING OUR<br />

CAVING HERITAGE<br />

Karen Moarkech<br />

BARLANGS IN<br />

BUDAPEST<br />

& UNDER AGGTELEK<br />

Emma Porter<br />

116 A RENDEZVOUS WITH 118 A YEAR INSIDE<br />

126 ROUEISS GEOLOGY 132 NEW DISCOVERIES<br />

MAMMOTH CAVE<br />

ROUEISS CAVE<br />

Rena Karanouh<br />

Rena Karanouh<br />

Hadi Kasammani,<br />

Wassim Hamdan,<br />

Nabil Shehab<br />

Issam Bou Jaoude<br />

6 | <strong>Al</strong>-Ouat ’Ouate 15 | 7

A canyon passage in Rahoue cave<br />

(Photo by Johnny Tawk)<br />

> Mgharet el Rahoue<br />

> The detailed survey of Chaos, Jiita.<br />

> The Pearls of Jiita.<br />

Thanks to our generous sponsors<br />

Shk. Khalid Bin Thani A. <strong>Al</strong> Thani,<br />

Mr. Ab<strong>du</strong>lla Bin Nasser <strong>Al</strong> Misnad<br />

and Mr. Marwan Zgheib, the<br />

coming issue of <strong>Al</strong>-Ouat’Ouate<br />

Magazine, issue 16, is already in<br />

the works. Several articles are<br />

already being researched. Here<br />

are some of the new discoveries,<br />

scientific reasearch and many<br />

varied cave related issues that<br />

will appear in our next issue:<br />

> Underground Activities<br />

> The Pearls of Kanaan.<br />

> Bats survey of Lebanon, 2010<br />

> Roueiss cave Archeology > Mgharet el Hadid<br />

<strong>Al</strong>-Ouat ’Ouate 16<br />

> Karst plateau > Colouration. > The karst of Lebanon<br />

8 | <strong>Al</strong>-Ouat ’Ouate 15 | 9

.بيرغ عباط ةراغلما هذهل<br />

مجح« مجلحا ثيح نم نانبل يف رواغلما ةعيلط يف نوكت نا ديرت يه<br />

.تلاكشتلا لامجو عافترلااو لوطلاو »تلاكشتلاو تارملما<br />

هذه مهاو .ةراغلما هذه لخاد رطسم نانبل يف راوغتسلأا خيرات<br />

نانبل يف راوغتسلاا ةدمعا دحأ ةدايقب ينينانبللا دي ىلع ةئاج تافاشتكلاا<br />

.يبكرك يماس ديسلا رواغلما يف بيقنتلل ينانبلا يدانلا يسسؤم دحاو<br />

عقوم نلاا وهو يولعلا قباطلا فاشتكا ىلع ةنس ينسمخ دعب<br />

رارساب ظفتتح لازت ام ةراغلما هذه .يبرعلا انلماع يف مارتحلااب ريدج يحايس<br />

.لمم سيلو قيطب لكشب نكلو ًايرود اهنع حاصفلاا ىلع دمتعتو<br />

ةراغلما هذه لمج ىلع طاوطولا ةلجم نم ددعلا اذه يف ءوضلا يقلن<br />

تارماغمو ناولأا ةددعتم تلاكشت نم اهلماعم نع حاصفلاا للاخ نم<br />

.اهلخاد تافاشتكلأا ةقفار ةقوشم<br />

هيلع ةظفالمحاو اتيعج ةراغلم بيرغلا عباطلا اذه عم ملقأتن نا بجي<br />

.ةمداقلا لايجلاا كلم هنلا<br />

Have you ever met Jiita?<br />

It can never bore you.<br />

You can never but enjoy every moment you spend in her realms. It<br />

amazes you when you go in but will beat you every time on your way out.<br />

But it is surely a cave with an attitude.<br />

Jiita cave wants to be the Giant of all caves in Lebanon. It desires to be<br />

the longest, the largest, the most beautiful and the one that holds the most<br />

cave secrets.<br />

It is the mother of our founding fathers. It witnessed the birth of our<br />

club in 1951. It triggered a swirl of caving adventures in Lebanon. Caving<br />

history was written in it.<br />

Fifty years since the discovery of its Upper Gallery, Jiita is now<br />

the most visited tourist attraction in Lebanon, its beauty rivaling many<br />

international show caves.<br />

This cave still holds on to many of its secrets. But it is slowly showing<br />

them to us bit by bit. The process is so slow it hurts, but still, anything<br />

worthwhile is worth waiting for, right?<br />

We pay tribute in this issue of the <strong>Al</strong>-Ouat’Ouate magazine to this<br />

amazing cave by showing you some of its new secrets: big columns;<br />

amazing stalagmites; stories from one of its great discoverers Mr. Sami<br />

Karkabi; its white and red galleries; and its climatic imprints...all this and<br />

more.<br />

We keep on watching for what she decides to unveil next.<br />

Connaissez-vous Jiita?<br />

Vous ne pourriez que prendre plaisir de chaque moment passé dans<br />

ses bras. Jiita vous surprendra et vous marquera de manière inoubliable<br />

au cours de votre visite et bien après. Cette grotte a sûrement un caractère,<br />

un charme, la plus longue des grottes libanaises, la plus jolie et surtout,<br />

la plus secrète. Elle est la mère de nos pères fondateurs et témoin de la<br />

naissance de notre club en 1951 où le berceau et l’histoire des aventures<br />

spéléologiques libanaises furent écrits.<br />

50 ans après la découverte des Galeries Supérieures, Jiita est la plus<br />

grande attraction touristique <strong>du</strong> pays et sa beauté rivalise celle des grottes<br />

internationales aménagées.<br />

Conservant minutieusement ses secrets, Jiita les dévoile peu à peu.<br />

Le progrès est lent et douloureux, mais les résultats prouvent le mérite des<br />

efforts.<br />

Dans cette édition <strong>du</strong> magazine <strong>Al</strong> Ouat’Ouate, nous rendons hommage<br />

à cette grotte en vous dévoilant, autant que possible, sa splendeur, ses<br />

colonnes, ses stalagmites, les histoires de son plus grand explorateur M.<br />

Sami Karkabi, ses galeries rouges et blanches, ses empreintes climatiques…<br />

tout cela et encore plus.<br />

Prenez plaisir dans l’attente de ses prochains dévoilements.<br />

10 | <strong>Al</strong>-Ouat ’Ouate 15 | 11

DYE-TRACING hISToRY<br />

Sami Karkabi | kraks@cyberia.net.lb<br />

LES<br />

PREMIERS<br />

TRAÇAGES<br />

ÀL’URANINE<br />

AU LIBAN<br />

Résumé<br />

Le désaccord qui opposait la Compagnie des Eaux<br />

de Beyrouth à la Société des Eaux <strong>du</strong> Kesrouan remonte à<br />

1911. Il concernait le captage des eaux de Nabaa el Laban<br />

à des fins d’irrigation. La Compagnie assurait qu’elle<br />

était lésée par ce captage, soupçonnant que les eaux qui<br />

s’écoulaient librement auparavant dans le lit <strong>du</strong> Nahr<br />

es Salib alimentaient aux travers de fissures la rivière<br />

souterraine de Jiita, ce cours d’eau souterrain ravitaillant<br />

à son tour la rivière souterraine. Trois traçages à la<br />

fluorescéine destinés à vérifier les faits furent entrepris en<br />

1913 dans des conditions précaires, rendant les résultats<br />

peu fiables.<br />

Afin de mettre fin à ce litige, le Général Weygand,<br />

Haut Commissaire de la République Française en Syrie<br />

et au <strong>Liban</strong>, institue par décision N°1998, le 26 juillet<br />

1923, une ‘’Commission’’ destinée à chercher l’origine de<br />

l’alimentation en eaux de la source principale <strong>du</strong> Nahr el<br />

Kelb.<br />

C’est à la suite de recherches effectuées dans les<br />

archives diplomatiques de Nantes (Mandat Syrie-<strong>Liban</strong>) et<br />

dans la revue <strong>Al</strong> Kulliyah de l’Université Américaine de<br />

Beyrouth qu’un certain nombre d’éléments relatifs à cette<br />

affaire ont été reconstitués.<br />

Il nous est apparu indispensable, vu la complexité de<br />

cette histoire, de retracer brièvement les différentes phases<br />

de son évolution.<br />

يذلا لدجلاب ةطيحملا فورظلاو لحارملا ىلا لاقملا اذه قرطتي<br />

هايم ةيعمجو توريب هايم ةكرش نيب نبللا عبن مرح ىلع لصح<br />

عبن نم ةقفدتملا هايملا نا لوقت ةكرشلا .1911 ماع يف ناورسك<br />

يفوجلا ىرجملا يذغتل بيلصلا ةقطنم يف قوقشلا يف روغت نبللا<br />

نم دكأتلل 1914 ةنس تلصح يتلا نيولتلا تايلمع .اتيعج عبنل<br />

نانبلل يماسلا ضوفملا ماق كلاذل .ًاعفن يدجت مل ةيرظنلا هذه<br />

1923 زومت يف 1998 مقر رارق رادصأب دراغنيو لارنجلا كاذنا ايروسو<br />

فيشراب ثحابلأ نيعتسي .لاكشلأا اذه يف رظنلل ةنجل نيعتب<br />

.تنان يف يسامولبدلا فيشرلااو ةيكرملأا ةعماجلا<br />

The disagreement on the catchment area of Nabaa el Laban between the<br />

Beirut Water Company and the Society of Waters of Kesrouan goes back to<br />

1911. The Company argued that the water passing freely in the bed of Nahr<br />

el Salib fed the underground river of Jiita through fissures and fractures.<br />

Three tracing tests using fluorescéine were undertaken in 1913 to prove<br />

this theory, proved inconclusive. To put an end to this debate, the General<br />

Weygand, high commissioner of the French République in Syria and in<br />

Lebanon, formulates a decision N°1998, on July 26th, 1923. The decision<br />

stipulates a «Commission» intended to search for the main source of Nahr<br />

el Kelb. This paper shortly illustrates the history and the stages regarding<br />

the issue at hand with the aid of information gathered from the archives of<br />

’Archives Diplomatiques de Nantes’ (Mandate Syria – Lebanon) and the <strong>Al</strong><br />

Kulliyah bulletin from the American University of Beirut.<br />

Il nous est apparu<br />

indispensable,<br />

vu la complexité<br />

de cette histoire,<br />

de retracer<br />

brièvement<br />

les différentes<br />

phases de son<br />

évolution.<br />

L’alimentation en eau de Beyrouth en 1870<br />

La capitale libanaise est ravitaillée dès 1870 par<br />

les eaux issues de la résurgence des grottes de Jiita,<br />

source principale <strong>du</strong> Nahr el Kelb. La concession de cette<br />

opération appelée ‘’Entreprise des Eaux de Beyrouth’’<br />

(devenue Compagnie des Eaux de Beyrouth) est accordée<br />

le 22 juillet 1870 par firman <strong>du</strong> Gouvernement Impérial<br />

Ottoman à M. Thevenin, ingénieur français, aux conditions<br />

suivantes : les eaux nécessaires seront empruntées au Nahr<br />

el Kelb en un point voisin de son embouchure dans la<br />

Méditerranée et seront con<strong>du</strong>ites par un canal d’amenée à<br />

l’usine de Dbayeh. Une partie de ces eaux servira de force<br />

motrice aux turbines qui la refouleront à Beyrouth, l’autre<br />

sera préalablement filtrée puis élevée au moyen d’une<br />

usine hydraulique qui s’établira et fonctionnera de façon<br />

à ne gêner ni les irrigations ni les moulins desservis par le<br />

cours d’eau. La quantité d’eau amenée à Beyrouth est fixée<br />

au minimum à 4000 m 3 par 24 heures. L’eau utilisée pour<br />

refouler à la vapeur 1 m 3 , exigerait l’emploi de dix autres<br />

mètres cubes environ par les installations hydrauliques.<br />

Le 6 novembre 1897 cette concession, à courir de la<br />

date <strong>du</strong> firman impérial, a été prolongée de 40 ans par une<br />

convention additionnelle.<br />

L’alimentation en eau <strong>du</strong> Kesrouan<br />

Le 3 avril 1893, un permis d’exploitation à but<br />

d’irrigation, <strong>du</strong> Nahr es Salib est accordé par la cour<br />

administrative <strong>du</strong> <strong>Liban</strong> au Cheikh Sejaan Maroun el<br />

Khazen. La Compagnie ne s’en inquiéta pas estimant que<br />

le Cheikh n’avait apparemment pas les moyens financiers<br />

d’aboutir mais soupçonnant toutefois, quoique n’en ayant<br />

aucune preuve, que les eaux issues de la résurgence de Jiita<br />

étaient directement alimentées par les eaux d’infiltration<br />

provenant <strong>du</strong> Nahr es Salib.<br />

En 1905, les droits <strong>du</strong> Cheikh Sejaan, étaient<br />

transférés au Cheikh Mansour el Bittar.<br />

Au mois de Juin 1907, Sélim Bey Chaker, sujet<br />

ottoman, natif <strong>du</strong> village libanais de Deir el Harf,<br />

représentant un syndicat de financiers d’Egypte, demande<br />

à la cour administrative de transférer encore une fois ces<br />

droits à son propre nom. Craignant que cette fois ne soit<br />

réalisé le projet, la Compagnie s’en alarme et proteste<br />

de façon formelle auprès de Youssef Pacha, Gouverneur<br />

<strong>du</strong> <strong>Liban</strong>. Cette crainte découle <strong>du</strong> fait, que si la quantité<br />

d’eau fournie pendant les mois d’hiver suffisait à tous les<br />

besoins, il n’en serait pas de même à l’étiage (de juin à<br />

novembre) pour refouler 640.000 m 3 d’eau à la vapeur. A<br />

ceci, s’ajouterait l’obligation de modifier les installations<br />

hydrauliques afin de les adapter à un débit plus ré<strong>du</strong>it que<br />

celui pour lequel elles avaient été calculées, d’où préjudice<br />

et énorme dommage.<br />

Ne tenant aucun compte de cette protestation ainsi<br />

que celle de la demande de Sélim Bey Chaker,<br />

12 | <strong>Al</strong>-Ouat ’Ouate 15 | 13

Youssef Pacha, accorde une nouvelle autorisation à Michel<br />

Bey Tueni. La Compagnie protesta alors auprès de la<br />

Sublime Porte, par l’intermédiaire <strong>du</strong> Wali de Beyrouth. Le<br />

Gouverneur <strong>du</strong> <strong>Liban</strong> fut invité à fournir des explications<br />

et le Gouvernement Impérial envoya de Constantinople<br />

un haut fonctionnaire des Travaux Publics mandaté pour<br />

effectuer une étude scientifique et géologique de concert<br />

avec les ingénieurs <strong>du</strong> Wilayet et <strong>du</strong> <strong>Liban</strong>. Toutefois,<br />

la Compagnie n’ayant qu’une confiance limitée dans<br />

les connaissances scientifiques de ces fonctionnaires,<br />

demanda au Wali de Beyrouth de leur adjoindre M. Elie<br />

Day, professeur de géologie au Collège Américain. La<br />

Compagnie profita d’une absence <strong>du</strong> dit professeur, pour<br />

se rendre dans le Kesrouan et faire seule son enquête. Le<br />

rapport fut présenté le 21 octobre 1908. Il contenait de<br />

nombreuses erreurs et lacunes. Le professeur Day se rend<br />

alors dans les vallées <strong>du</strong> Nahr es Salib et <strong>du</strong> Nahr el Kelb.<br />

Son étude conclut à la probabilité d’une communication<br />

souterraine entre le haut Nahr es Salib et les grottes de<br />

Jiita. Une série d’observations confirmèrent cette opinion.<br />

Dès lors, Michel Bey Tueni, renonça à continuer ses<br />

démarches.<br />

Extrait de l’étude <strong>du</strong> Pr. A. E. Day publié en 1912:<br />

… The river bed at Meiruba and the Jaita<br />

cave are both in the lower (Jurassic)<br />

limestone of Lebanon, and it is probable<br />

that the whole of the subterranean channel<br />

is excavated in this formation. Caves are<br />

common in limestone countries, being formed<br />

by the solvent action of the water of the<br />

rains and the snows as it percolates through<br />

the rock. While it has been stated as<br />

probable that the water which flows out of<br />

the Dog River cave, it must be remembered<br />

that this not been proved. If a large amount<br />

of solution of some harmless coloring matter<br />

were turning into stream near Meiruba at<br />

the time of low water in the latter part of<br />

the summer, while competent persons made<br />

careful observations at the Dog River cave,<br />

it might thereby be ascertained whether or<br />

not the water of Meiruba forms a part of<br />

the subterranean river. This would entail<br />

considerable expense and careful attention<br />

from skilled observers. A demonstration of<br />

another character seems likely to be made in<br />

the near future. A company has been formed<br />

to divert the water of Neb’-ul-Asal by an<br />

aque<strong>du</strong>ct, which shall take it to the region<br />

of Reifun, Ajaltun, and Ashkut. Preliminary<br />

surveys were made recently and it may be<br />

that the plan will be carried out. It is to<br />

be hoped that if is results in a diminution<br />

of the output of water from the Dog River<br />

cave, the amount remaining may prove to be<br />

sufficient for the wants of Beirut. The<br />

Beirut Water Company contested the right of<br />

the new Company to divert the head waters of<br />

the Dog River systems, but the litigation<br />

resulted unfavorably to the Beirut Company.<br />

(réf. <strong>Al</strong>-Kulliyah,<strong>Al</strong>fred Ely Day, Professor<br />

of geology - A.U.B. - Vol. III N°3, p.72 –<br />

January 1912).<br />

Sélim Bey Chaker revint à la charge en 1911. Malgré<br />

les protestations de la Compagnie, la concession lui<br />

fut finalement accordée par «mazbata» sanctionné le<br />

7 juillet 1911 par Youssef Pacha, Gouverneur <strong>du</strong> <strong>Liban</strong>.<br />

Ce dernier accorde à M. Sélim Bey Chaker le droit de la<br />

fourniture, d’alimentation et d’irrigation à divers villages<br />

<strong>du</strong> Kesrouan. Le transfert de cette concession prend<br />

nom de ‘’Société des Eaux <strong>du</strong> <strong>Liban</strong>’’. Elle sera reportée<br />

quatre mois plus tard par son bénéficiaire à une société<br />

constituée par un groupement anglais. Le gouvernement de<br />

Constantinople ne parait pas être intervenu dans l’affaire.<br />

Sur quoi la Compagnie adressa le 1er novembre 1911<br />

au Ministère des Travaux Publics une dépêche le rendant<br />

responsable des dommages que l’octroi de cette concession<br />

entraînerait. Suite à cette dépêche, le Ministre des Travaux<br />

Publics nomma une commission d’experts et adressa au<br />

Wali de Beyrouth, en date <strong>du</strong> 17 novembre 1911, l’ordre<br />

de faire rechercher par cette commission, soit par matières<br />

colorantes, soit par examen microscopique, si oui ou<br />

non, il y avait communication entre les eaux <strong>du</strong> Nahr es<br />

Salib et les grottes de Jiita et, en attendant les résultats, de<br />

suspendre les travaux. Puis le temps passa et rien ne fut<br />

exécuté.<br />

La Compagnie protesta à nouveau, mais cette fois<br />

par acte notarié <strong>du</strong> 31 janvier 1912. Cette démarche<br />

n’ayant pas plus de succès que les autres et la Commission<br />

Officielle n’ayant aucune velléité de remplir sa mission, le<br />

Consul Général de France intervint en raison des intérêts<br />

français considérables représentés dans la Compagnie, et,<br />

sur son désir, celle-ci lui adressa le 14 février 1913 un<br />

rapport complet réclamant de surcroît son intervention<br />

personnelle.<br />

Cette fois, après un nouvel ordre <strong>du</strong> Ministère des<br />

Travaux Publics en date <strong>du</strong> 2 avril 1913, le Gouvernement<br />

<strong>du</strong> <strong>Liban</strong> s’exécuta et ainsi que le Wilayet le faisait de<br />

son côté, désigna en Août une Commission d’experts,<br />

composée de membres <strong>du</strong> Conseil Administratif <strong>du</strong> <strong>Liban</strong><br />

et <strong>du</strong> Wilayet afin de réexaminer la situation.<br />

Les premières colorations<br />

Les colorations de la Société des Eaux <strong>du</strong> Kesrouan<br />

et de la Compagnie des Eaux de Beyrouth (septembre et<br />

novembre 1913).<br />

1 - la Compagnie fit faire par son personnel un<br />

essai privé de coloration qui, exécuté le plus discrètement<br />

possible (sans témoins accrédités) et sans attirer<br />

l’attention, donnait des résultats prouvant l’existence<br />

d’une communication souterraine entre le Nahr es Salib<br />

et le Nahr el Kelb. Ces résultats sont consignés dans un<br />

procès-verbal d’analyse établi le 6 septembre 1913 par<br />

le Docteur GUIGES, professeur à la Faculté Française<br />

de Médecine. Ce document n’a pas été trouvé dans les<br />

archives diplomatiques de Nantes.<br />

2 – la seconde coloration (20kg d’uranine versés à<br />

Nahr es Salib) réalisée le 30 septembre 1913 en privé par<br />

la ‘’Concession’’ n’a donné aucun résultat positif. Il reste<br />

que ces deux expériences restent entachées <strong>du</strong> même vice,<br />

celui d’une trop courte attente à la sortie des eaux de la<br />

résurgence de Jiita et ne peuvent servir de témoignage.<br />

3 - La troisième expérience (30kg d’uranine),<br />

officielle cette fois-ci, a été exécutée le 6 novembre 1913<br />

par une commission déléguée par la Compagnie. Elle fut<br />

entourée d’une publicité inévitable. Malheureusement la<br />

Commission eut le tort d’attendre trop peu de temps à la<br />

grotte de Jiita, et de faire ses prélèvements d’eau avant<br />

l’arrivée de la grande masse de colorant, qui ne survint,<br />

prétend-elle, qu’après son départ et dont les habitants<br />

de Beyrouth ont gardé le souvenir car ils le burent deux<br />

jours <strong>du</strong>rant. Mais cette présence de colorant n’avait<br />

pas été constatée officiellement à la grotte même, et les<br />

échantillons prélevés prématurément par la Commission<br />

n’ayant donné de traces qu’au fluoroscope, sans coloration<br />

visible à l’œil, la majorité de la Commission déclara<br />

l’expérience insuffisante.<br />

DOCUMENT N° 9 – Rapport <strong>du</strong> chimiste James A. Patch, chargé par la Compagnie des Eaux de Beyrouth de prélever et<br />

d’analyser les échantillons d’eau à la grotte de Jiita. Ce rapport est daté <strong>du</strong> 8 novembre 1913, c’est-à-dire au surlendemain<br />

de la coloration effectuée avec 30kg de fluorescéine au niveau de Nabaa el Mghara dans la région de Meiruba. Comme<br />

signalé plus haut, l’attente fut trop courte et seul le témoignage tardif de M J. Patch (voir plus loin, “The Dog river dyed<br />

green” confirme par la suite la réussite de l’expérience.<br />

Dear Sir,<br />

At your request on Nov 6, I took in collecting and examining samples of water from the<br />

Nahr el Kelb as issues from the cave of Jiita. The object of the test was to determine if<br />

the water contained any trace of the special dye called ‘’uranine’’ which had been added to<br />

the extent of 30 kilos in the Nahr Salib before it disappears in the ground.<br />

I took the first sample at 10.50 A.M. Thursday, Nov.6th. It consisted of an ‘elfeeyah’<br />

(approximately 3 liters) and being perfectly clear, was reserved for comparison. At 11.15<br />

A.M. we began to take regular samples of 250 cc. each every 15 minutes, and continued<br />

the sampling without a break until 8 A.M. Friday morning, the samples sent to Beirut for<br />

further analysis. Here each was treated and traces which might not be evident in the tube<br />

comparisons. Colorimetric comparisons of the samples which in 1-10,000,000 solution of<br />

uranine showed them free from color. As a result of the examination of original samples and<br />

later the collective samples, I am able to state that between the hours of 11,15 A.M. on<br />

Thursday and 8 A.M. on Friday, Nov. 6-7, no trace of uranine could be found in water.<br />

Trusting that report will serve you need, I remain,<br />

Yours very sincerely,<br />

(Sgd) James A. Patch<br />

THE DOG RIVER DYED GREEN<br />

<strong>Al</strong>-Kullyah, Vol. N°3 - January 1914<br />

LES PREMIERS TRAÇAGES<br />

À L’URANINE AU LIBAN<br />

In <strong>Al</strong>-Kulliyah for January 1912 appeared an interesting article giving a description of the<br />

Dog River Cave and of the experiences of various exploring parties who have made excursions<br />

into the cave. Towards, Professor Day, discusses the possibility of the water flowing<br />

from the cave being the same as that which sinks into the river bed of Nahr us-Salib near<br />

Meiruba. Professor Day suggests, as a method of proving this connection, that there be<br />

emptied into the Nahr-us-Salib near Meiruba a large quantity of some harmless dye which, if<br />

there is a connection between the streams, would appear later in the water at the Dog River<br />

Cave.<br />

Considerable importance has recently become attached to the proving or disproving of<br />

this connection between the two rivers. The water supply of the City of Beirut is mainly<br />

drawn from the stream issuing from the Dog River Cave. Another water company is now engaged<br />

in reconstructing tunnels and aque<strong>du</strong>cts preparatory to diverting the water of Nar-ul-Assal,<br />

which at present flows into the Nahr-us-Salib, and so, perhaps eventually, into the Dog<br />

River, to supply the needs of the towns of Reifun, Ajaltun and Ashkut. If, as many believe,<br />

the Neb-ul-Assal water furnishes one-fifth of the Dog River supply, then the leading away of<br />

this amount would appreciably decrease the Beirut supply, especially at the end of the dry<br />

season.<br />

The writer was recently called to assist in making such a color test as Professor Day<br />

has suggested. By previous arrangement with both the Beirut and the Reifun water companies a<br />

large quantity of a special dye, called ‘’uranine’’, was dissolved in water and turned into<br />

the Nahr-us-Salib near Meiruba at seven o’clock on the morning of Nov. 6th, last. Uranine<br />

when in dilute solutions, imparts to water a beautiful green fluorescence, greater dilution<br />

can still observed by looking through a considerable length of solution in a colorimetric<br />

tube. On the occasion here described sufficient uranine (30 kilograms) was poured into Nahrus-Salib<br />

to give a strong color to all the water that then flowing from the Dog River Cave<br />

in twenty-for hours (about 130.000 cubic meters). The color was dissolved and mixed with<br />

the stream by representatives of the Beirut Water Company. Soon after the experiment was<br />

made, tests were begun on the water flowing from the Dog River Cave. Samples were collected<br />

and tested every fifteen minutes until eight o’clock the following morning, that is, until<br />

twenty-five hours elapsed after the color was added to the Nahr-us-Salib at<br />

14 | <strong>Al</strong>-Ouat ’Ouate 15 | 15

Meiruba. From the length of time it took the color to travel a given distance in the stream<br />

above, it had been calculated that the color ought to appear at the cave in about nine<br />

hours. Sixteen additional hours were considered a very safe margin to wait for appearance<br />

of the uranine. However, <strong>du</strong>ring all this time not the slightest indication of coloration<br />

appeared.<br />

It was a great disappointment to many of the watchers of this interesting experiment to<br />

realize that their belief in a close connection between the two streams must be altered.<br />

<strong>Al</strong>l the small samples of water collected <strong>du</strong>ring the test were mixed in two-hour samples<br />

in large bottles and brought to the College for further testing, but with the same negative<br />

results. The most careful examination failed to show any signs of coloration and a report<br />

was made out to that effect.<br />

On the morning of November 12th, six days later, a messenger from the water company<br />

at Dubeiyeh appeared at the College to say that at six o’clock that morning the water of<br />

the Dog River began to run green. Mr McCann, representing the writer, went out on the next<br />

train and hastened to the cave to make note of the facts. He reported on his return the<br />

green appearance of the water and brought with him a sample of the colored water to be<br />

tested. Uranine was present but in a very minute quantity. The following morning the writer<br />

tested the city supply in the laboratory and in his house and found it also green but much<br />

less colored than the cave water. For more than a day the city of Beirut drank green water<br />

without knowing it. Those who looked at the sample in the writer’s laboratory can testify<br />

to the fact that it was really green.<br />

The experience of the previous week had altered our belief in regard to the origin<br />

of the Dog River water. Now this new incident again upset out conclusions. Surely the<br />

green in the water must have come from Meiruba, but where had it been all this time? How<br />

could it have been concealed for six days within a distance of thirteen kilometers? At a<br />

previous test one month before a similar tardy appearance of the color was reported to have<br />

occurred.<br />

After all, then, Professor Day’s conjecture is perhaps correct. Until some new data<br />

is presented it is natural to assume that the water, which is sinking into the stony river<br />

bed of the Nahr-us-Salib, appears again at the Dog River Cave. Not many months hence a more<br />

certain proof of the truth or falsity of the assumption will be furnished by the actual<br />

diverting of the Neb-ul-Assal waters.<br />

James A. Patch<br />

Malgré l’apparition <strong>du</strong> colorant à Dbaiyeh et dans<br />

les robinets de Beyrouth, la Commission n’osa conclure<br />

l’exactitude des résultats obtenus. La Commission de 1913<br />

se proposait de renouveler ses expériences à la fin de l’été<br />

de 1914, mais survient la guerre, et la question des Eaux <strong>du</strong><br />

Nabeh el Assal tombe dans un sommeil de sept ans. Quand<br />

la Société des Eaux <strong>du</strong> Kesrouan manifeste l’intention de<br />

les reprendre, la Compagnie des Eaux de Beyrouth proteste<br />

de nouveau et obtient le 5 octobre 1922 <strong>du</strong> gouverneur <strong>du</strong><br />

Grand <strong>Liban</strong> la nomination d’une commission nouvelle<br />

chargée de réaliser le programme interrompu par les<br />

hostilités.<br />

Mais cette commission présidée par le Directeur<br />

des Travaux Publics <strong>du</strong> Haut-Commissariat, posa dans<br />

les deux séances qu’elle tint, les 12 et 14 <strong>du</strong> même<br />

mois, la question préjudiciable suivante : nommée par<br />

le Gouvernement <strong>du</strong> Grand <strong>Liban</strong>, héritier de l’ancienne<br />

Administration <strong>du</strong> <strong>Liban</strong>, avait-elle le droit, le cas<br />

échéant, de conclure à la responsabilité pécuniaire de ce<br />

Gouvernement ? A la majorité, elle estima que non, et<br />

conclut à son incompétence.<br />

Devant cette fin de non-recevoir, la Compagnie des<br />

Eaux de Beyrouth se retourna vers le Haut-Commissariat.<br />

Elle lui demanda de constituer une commission définitive<br />

indépendante <strong>du</strong> Grand <strong>Liban</strong> et susceptible de mener à<br />

bien les expériences ajournées depuis neuf ans. La saison<br />

était trop tardive pour y procéder en 1922.<br />

Afin de mettre fin à ce litige, le Général Weygand,<br />

Haut-Commissaire de la République Française en Syrie<br />

et au <strong>Liban</strong>, institue par décision N°1998, le 26 juillet<br />

1923, une ‘Commission’ destinée à chercher l’origine de<br />

l’alimentation en eaux de la source principale <strong>du</strong> Nahr el<br />

Kelb.<br />

Cette «Commission» comprenait deux représentants<br />

<strong>du</strong> Haut-Commissariat, deux représentants de<br />

l’Administration <strong>du</strong> Grand <strong>Liban</strong>, un représentant de la<br />

Compagnie des Eaux de Beyrouth, le concessionnaire des<br />

Eaux <strong>du</strong> Nabeh el Assal, plus un représentant de la Société<br />

rétrocessionnaire, ainsi que deux experts indépendants<br />

de l’Administration et des parties en cause. Le point<br />

essentiel qui nous intéresse ici est la procé<strong>du</strong>re à suivre<br />

pour des expériences de coloration des eaux <strong>du</strong> Nahr es<br />

Salib au moyen d’uranine fournie par la Compagnie des<br />

Eaux de Beyrouth. Pour réaliser ce projet, une commission<br />

parallèle est créée, composée d’un ingénieur chimiste,<br />

d’un géologue, d’observateurs en amont lors de l’injection<br />

<strong>du</strong> colorant et d’observateurs en aval à la résurgence pour<br />

certifier l’arrivée <strong>du</strong> colorant. En outre, et afin d’assurer le<br />

bon déroulement de l’opération et éviter toute équivoque,<br />

une dizaine de gendarmes sont affectés à l’entrée de la<br />

grotte de Jiita.<br />

Les opérations préparatoires comprenaient une<br />

reconnaissance des lieux permettant une étude géologique,<br />

la localisation des pertes supposées, une mission de<br />

jaugeage et bien enten<strong>du</strong> le programme concernant<br />

l’opération de coloration elle-même.<br />

A – Considérations géologiques<br />

(Larges extraits <strong>du</strong> rapport géologique (Septembre<br />

1923) de M. Odinot professeur de Géologie à l’école<br />

Française d’Ingénieurs de Beyrouth (Fig. 1). Note : lire en<br />

place de Ouadi bou Roqaa, Nahr es Salib tel qu’indiqué sur<br />

les cartes en 1923.<br />

Nous avons remonté le Nahr es Salib un kilomètre environ en amont de Nabaa el Mghâra sur les premières pentes <strong>du</strong><br />

Sannine. L’endroit où est établi notre campement est assez caractéristique ; en aval les couches sont calcaires, plongent<br />

25 degrés environ O.E. en direction N.S. et se rétablissent horizontalement à hauteur de Maïroûba où les parois de la<br />

rivière, deviennent très abruptes jusqu’au moment où nous avons suivi le lit de la rivière, c’est-à-dire jusqu’au droit de<br />

Reyfoun. En amont les couches calcaires plongent sous une puissante venue de basalte qui les a métamorphosés. L’arête<br />

rocheuse aussi bien côté Maïroûba que côté Mazraat Kfar Debian, est recouverte dans ses parties horizontales par les<br />

grés rouges. On peut donc se situer logiquement dans la partie où ont eu lieu les essais, l’on se trouve dans les calcaires<br />

les plus anciens de la montagne <strong>du</strong> <strong>Liban</strong>, c’est-à-dire vraisemblablement dans le Jurassique supérieur et sous le dernier<br />

étage le plus ancien <strong>du</strong> crétacé, le grès <strong>du</strong> néocomien qu’on retrouve dans la vallée <strong>du</strong> Nahr el Kelb, en aval de la grotte<br />

de Jiita, mais ici les couches sont presque verticales.<br />

Ces considérations permettant ainsi de présumer que le fond de la vallée n’est pas imperméable mais que les apports<br />

de la rivière ont constitué une sorte de colmatage jusqu’à présent perméable de la partie inférieure de la vallée en la<br />

nivelant à peu près. Ceci laisse supposer et permet de considérer qu’il y a un lit souterrain inférieur au niveau actuel <strong>du</strong><br />

lit aérien avec lequel il y aura communication tant que le colmatage ne sera pas complet. Mais nous devons dire aussi<br />

que par suite <strong>du</strong> cours naturel des choses, l’effet de colmatage sera certainement d’amener un jour le lit souterrain à<br />

être aérien sur tout son parcours. L’inclinaison des couches dans la partie amont <strong>du</strong> Platane semblerait indiquer que les<br />

eaux qui se perdent dans cette partie de la rivière peuvent être captées et dirigées vers et sous la circonscription <strong>du</strong><br />

Sannine, puisque ces couches plongent à<br />

l’Est. Les eaux qui s’infiltrent dans les lits de<br />

stratification sont vraisemblablement dirigées de<br />

ce côté. Un réseau souterrain de fissures doit<br />

certainement exister dans toute la région<br />

commandée par le Sannine pouvant modifier assez<br />

considérablement le système d’écoulement des<br />

eaux superficielles et il est très probable qu’il doit<br />

y avoir d’assez grandes différences entre les<br />

lignes de séparation des eaux à la surface (eaux<br />

pluviales) ou bassin topographique et la ligne de<br />

séparation des eaux souterraines (eaux<br />

d’infiltration) ou bassin d’alimentation<br />

proprement dit.<br />

Pour parler en complète connaissance de cause il faudrait faire l’étude <strong>du</strong> bassin hydrographique complet <strong>du</strong> Nahr el<br />

Kelb. Mais ceci demande <strong>du</strong> temps. Ce qu’il y a de certain, c’et que la nature <strong>du</strong> terrain qui est fissuré en grand dans un<br />

seul étage géologique rend probable au plus haut degré la communication entre le bas et le haut, entre le Nahr el Kelb et<br />

le Nahr es Salib.<br />

Il sera beaucoup plus délicat de déterminer dans quelles proportions, si même cela est possible, car dans des<br />

expériences sincères et exemptes de toute critique au point de vue qui nous occupe, il faudrait faire surveiller tous les<br />

points d’où peut sortir l’eau. L’évaluation de la relation quantitative entre les grottes de Jiita et le Nahr es Salib peut<br />

se faire en serrant de très près la vérité, à l’aide d’un colorant sensible dans le genre de l’uranine. Les conditions<br />

géologiques sont donc au plus haut degré favorables à ce que les eaux qui sortent aux grottes de Jiita constituent une<br />

résurgence partielle des eaux per<strong>du</strong>es aux environ de Maïroûba. Concernant ce dernier point, des jaugeages dans les<br />

bassins supérieurs et inférieurs renseigneront utilement sur la perméabilité des lits et les quantités disponibles utilisées<br />

et per<strong>du</strong>es de l’eau en question.<br />

Beyrouth, le 28 septembre 1923.<br />

Odinot<br />

B – Localisation des pertes<br />

Six pertes ont été repérées avant de<br />

subir les injections d’uranine (Fig. 2). Deux<br />

sur la rive gauche : gouffres <strong>du</strong> Platane et<br />

de AÏn Ouarka, deux sur la rive droite :<br />

gouffres de Zeiat et <strong>du</strong> moulin, ainsi que<br />

deux pertes dans le lit filtrant à l’amont et<br />

l’aval <strong>du</strong> barrage initial dit aussi barrage de<br />

la Cie des Eaux <strong>du</strong> <strong>Liban</strong>.<br />

LES PREMIERS TRAÇAGES<br />

À L’URANINE AU LIBAN<br />

16 | <strong>Al</strong>-Ouat ’Ouate 15 | 17<br />

Fig. 1<br />

Fig. 2

BASSIN SUPÉRIEUR<br />

lit/sec m3 /24 h lit/sec m3 /24h.<br />

Nabaa el Assal canal supérieur de Mazraat 50 4320 Nabaa el Assal 200mètres aval confluent 449 38800<br />

À la source lit torrentiel 585 50544<br />

Total à la source 635 54864<br />

Fig. 3<br />

Nabaa el Laban canal de Mazraat 40 3456 Nahr el Salib<br />

lit torrentiel 14 1200 sous Harajel barrage maçonné 504 43545<br />

total de la source 54 4656 sous Maïroûba aval Chébli 250 21600<br />

Nabaa el Mghara à la perte 59 510 Nabaa el Qana 37 320 0<br />

a la résurgence 281 24260<br />

BASSIN INFÉRIEUR<br />

Nahr el Kelb résurgence Jiita 17 1000<br />

Soit un total de 191.435 m3/jour <strong>du</strong> bassin supérieur pour 171.000 m3/jour à la résurgence <strong>du</strong> Nahr el Kelb.<br />

C – Les sources principales se déversant dans le<br />

Nahr es Salib (Fig. 3)<br />

Par ordre d’importance: Nabaa el Laban, Nabaa el<br />

Assal, Nabaa el Mghara, Nabaa el Qana, Nabaa el Hadid.<br />

D – Les Jaugeages<br />

Vingt trois jaugeages ont été effectués dans les<br />

bassins supérieurs et inférieurs des pertes présumées <strong>du</strong><br />

Nahr es Salib. Nous n’en retiendrons que sept, résumant<br />

l’ensemble de ces mesures empruntées aux résultats de la<br />

mission Odinot/Troccaz (Fig. 4).<br />

Il nous semble intéressant par ailleurs de relever<br />

une observation concernant les eaux de Nabaa el Laban<br />

faite lors de la reconnaissance des lieux. (Extrait <strong>du</strong><br />

compte-ren<strong>du</strong> de monsieur Patras, gardien <strong>du</strong> barrage de la<br />

Cie des Eaux de Beyrouth).<br />

Nabaa el Laban offre la particularité d’être<br />

la source la plus importante de cette région pendant la<br />

saison des pluies à partir de Janvier et jusque vers le<br />

15 août. A cette dernière date, la quantité d’eau diminue<br />

brusquement. Il paraît que cette baisse (observée à la<br />

source en 1923) de 1.5m au moins en une nuit) serait très<br />

régulièrement observée dans une période de 3 jours autour<br />

<strong>du</strong> 15 août et même, tomberait invariablement le 15, 16<br />

et 17 de ce mois; Le fait est assez curieux et mérite d’être<br />

étudié. Il peut s’expliquer facilement par l’existence d’un<br />

siphon ou d’un système de plusieurs siphons dont l’un se<br />

désamorcerait à cette époque de l’année. Ceci implique<br />

soit une très grande régularité annuelle dans le régime de<br />

précipitations atmosphériques soit l’existence d’une masse<br />

d’eau dont le niveau descendrait mathématiquement à la<br />

même cote au même moment de l’année.<br />

Hypothèse<br />

La seconde supposition se rapporte aux résultats<br />

d’une plongée et d’une topographie exécutée par C.<br />

Locatelli et J-J Bolanz (voir aussi <strong>Al</strong> Ouat’Ouate N°7-<br />

8/1992-1993, pp.18-20).<br />

Deux plongées ont eu lieu dans la source de Nabaa<br />

el Laban. La première le 11/08/1992 et la seconde le<br />

lendemain 12. La visibilité était meilleure que la veille. Au<br />

regard <strong>du</strong> plan et de la coupe présentée en trois dimensions<br />

la présence de galeries latérales décrites par J-J Bolanz<br />

(pré-rapport d’expédition - Fédération Française de<br />

<strong>Spéléo</strong>logie – Mission <strong>Liban</strong> 92) nous incite à croire à la<br />

présence de siphons latéraux désamorcés pour l’instant à<br />

savoir (Fig. 5) :<br />

… je tire 42 mètres dans la galerie ovale aperçue hier.<br />

Au début elle est ovale, 2m par 1, mais rapidement elle<br />

diminue de taille pour atteindre 1m par 0,80. Le passage<br />

est loin d’être aisé, car le rocher est hérissé d’aspérités<br />

qui vous accrochent partout. De plus, le faible courant<br />

n’est pas suffisant pour évacuer la touille provoquée par<br />

les bulles …(Intéressante observation de ce réseau à faible<br />

courant alors que J-J Bolanz indiquait plus haut …). C’est<br />

bien 18h00 quand nous arrivons à la source. La visibilité<br />

n’est que de trois mètres et le courant aussi fort que la<br />

veille …<br />

E – La coloration<br />

Il serait fastidieux de décrire les différentes étapes<br />

qui ont marqué la coloration. Le rapport manuscrit de 13<br />

pages en écriture serrée de Mr. Claris, professeur de chimie<br />

à l’Ecole Française d’Ingénieurs de Beyrouth et chargé<br />

de l’opération ‘’coloration’’ en décrit minutieusement<br />

les infimes détails, y compris celle de l’analyse de 221<br />

échantillons d’eau prélevés à la grotte de Jiita. Sachons<br />

toutefois que de nombreux observateurs témoins de la<br />

démarche étaient présents sur les lieux. Ils étaient partagés<br />

en deux équipes comprenant une commission d’amont et<br />

une d’aval. La commission d’amont supervisait l’injection<br />

d’uranine, celle d’aval étant chargée de vérifier l’arrivée <strong>du</strong><br />

colorant et <strong>du</strong> prélèvement des échantillons.<br />

Le tableau ci-joint résume les horaires des<br />

opérations d’injection faites entre le barrage de la<br />

Compagnie et le gouffre de Aïn Ourka, distant d’environ<br />

300 mètres (Fig.4).<br />

Réapparition de la coloration à la résurgence de la<br />

grotte de Jiita<br />

Les eaux de Jiita sont apparues colorées à l’œil nu,<br />

à partir <strong>du</strong> lundi 10 septembre à 2 heures <strong>du</strong> matin. La<br />

coloration a été très caractéristique, les lundi 10 septembre,<br />

mardi 11 septembre, mercredi 12 septembre pour diminuer<br />

progressivement et ne plus être visible le mercredi 19<br />

septembre (Fig. 6).<br />

L’existence de la communication entre les<br />

eaux <strong>du</strong> Nahr es Salib et la grotte de Jiita est ainsi<br />

irréfutablement prouvée.<br />

Il y aurait lieu suite à cette expérience de chercher<br />

à déterminer le volume des eaux <strong>du</strong> Nahr es Salib arrivant<br />

à Jiita. La quantité totale d’uranine versée dans le Nahr es<br />

Salib de 43kg600 est-elle réapparue en totalité à la grotte?<br />

Les responsables avancent le chiffre de 75%. Et pourtant<br />

s’il faut recouper les témoignages de l’époque, il y aurait<br />

eu des pertes relativement importantes de colorant. A<br />

savoir :<br />

1 – Que l’uranine employée était de même<br />

provenance, mais une partie avait été importée<br />

antérieurement à la guerre de 1914-18 et l’autre<br />

dernièrement. 24kg datant <strong>du</strong> stock de 1913 se<br />

présentaient compact et difficiles à dissoudre. Il est permis<br />

de croire que l’uranine pouvait ne pas être homogène et<br />

qu’une partie n’aurait pas été dissoute, mais probablement<br />

précipitée. La partie nouvellement importée était<br />

enveloppée dans des boîtes en fer blanc, hermétiquement<br />

clauses, chaque boîte contenant 0,200 gr. Lors des<br />

LES PREMIERS TRAÇAGES<br />

À L’URANINE AU LIBAN<br />

colorations il a été constaté que l’uranine nouvelle était<br />

facilement dissoute dans l’eau et qu’il n’en était pas de<br />

même de l’ancienne que, retirée en blocs, il fallait ré<strong>du</strong>ire<br />

en poudre.<br />

2 - Une boîte de 200 grs renversée a été per<strong>du</strong>e<br />

au gouffre <strong>du</strong> Moulin, à laquelle il faut ajouter ce qui est<br />

resté en particulier dans les boîtes en carton où l’uranine<br />

n’était pas en poudre et qu’il a été impossible d’extraire<br />

entièrement. Il y a eu certainement des pertes d’uranine<br />

provenant de ces diverses manipulation. L’uranine<br />

nouvelle moussait facilement, l’uranine ancienne presque<br />

pas. Lors des colorations quelle que soit l’uranine, il<br />

semblait que la coloration était identique, mais comme la<br />

concentration était très chargée, il était difficile d’apprécier<br />

à l’œil une différence.<br />

18 | <strong>Al</strong>-Ouat ’Ouate 15 | 19<br />

Fig. 4<br />

Fig. 5<br />

Fig. 6

3 – Ne peut-on craindre vu les faits<br />

exposés que les résultats trouvés ne fussent<br />

légèrement affaiblis par la supposition que<br />

l’uranine ancienne avait les mêmes propriétés<br />

que celle contenue dans les boîtes nouvelles ?<br />

4 – Les canaux d’irrigations situés<br />

entre Zeiat et le canal de Reyfoun sont restés<br />

ouverts pendant la <strong>du</strong>rée des opérations (canal<br />

<strong>du</strong> Moulin, canal amont <strong>du</strong> Platane, canal<br />

Chébli). L’eau qui s’est répan<strong>du</strong>e dans ces<br />

terrains qui est restée stagnante et colorée<br />

jusqu’au 22 septembre, laisserait croire<br />

que la matière colorante est descen<strong>du</strong>e très<br />

lentement à travers les terrains. Une partie<br />

s’est évaporée et d’autres a été dissoute<br />

ou fixée par les plantes et les racines. Ici<br />

se trouve donc une perte impossible à<br />

évaluer. Ce qui est à retenir, car étant donné<br />

l’abaissement progressif de l’uranine au débit<br />

(voir diagramme de restitution, Fig. 6), la<br />

courbe aurait dû atteindre l’axe X plus tard<br />

que le point fixé. Autre argument concernait<br />

le débit <strong>du</strong> Nahr es Salib. La Compagnie<br />

arguait que les 4, 5, 6 septembre 1923, un<br />

Shlouk (vent chaud) d’une rare intensité<br />

sévissait au <strong>Liban</strong>. Il aurait augmenté<br />

considérablement l’évaporation, concentrant<br />

le colorant dans certaines parties où les eaux<br />

étaient stagnantes, faussant le calcul des<br />

pertes.<br />

Messieurs Odinot et Troccaz, ont<br />

effectué des mesures exactes <strong>du</strong> débit des<br />

eaux en octobre. Ils ont trouvé en amont <strong>du</strong><br />

barrage 43545m 3 par jour, or un mois plus<br />

tôt, c’est-à-dire vers le 4 septembre celui-ci<br />

devait être selon appréciation de 15% environ<br />

supérieur, soit 50000 m 3 de débit d’eau par<br />

jour.<br />

5 - Les barrages amont et aval<br />

péchaient par leur étanchéité. Il était<br />

nécessaire de réévaluer les pertes d’eau par<br />

infiltration et par conséquent <strong>du</strong> colorant<br />

per<strong>du</strong>.<br />

Quelques observations<br />

– La coloration met environ une<br />

DIZAINE D’HEURES pour franchir les 3 km<br />

qui existent entre le barrage de la Compagnie<br />

des Eaux <strong>du</strong> <strong>Liban</strong> et le point où les eaux<br />

disparaissent totalement dans le lit de la<br />

rivière (Fig. 7). La côte approximative de ces<br />

points est respectivement 1180 et 1160 mètres<br />

environ, soit une différence d’altitude de 20<br />

mètres.<br />

– D’autre part, la coloration met CENT<br />

TRENTE HEURES environ pour franchir<br />

le trajet souterrain estimé à seize kilomètres<br />

entre le point de coloration (1180m) et où<br />

elles surgissent à Jiita (60m).<br />

Fig. 8<br />

Conclusion<br />

En guise de conclusion, ce texte manuscrit de M. Claris (1923),<br />

(Fig. 8).<br />

Annexe<br />

Cet encadré paru dans le quotidien libanais L’Orient-Le Jour <strong>du</strong> 30<br />

juillet 2008 (signé Victor Fleury) nous informe qu’un vaste programme<br />

d’étude a été lancé en collaboration des organisations italiennes dans le<br />

but de préserver les eaux <strong>du</strong> Nahr el Kelb.<br />

En voici de larges extraits :<br />

“Un projet d’étude sur la qualité de l’eau <strong>du</strong> Nahr el Kelb a<br />

été présenté dernièrement lors d’un séminaire à l’Université Notre-<br />

Dame de Zouk Mosbeh. Les représentants des principaux partenaires<br />

de cette initiative, le ministre de l’Energie et de l’Eau, le Centre de<br />

recherche de l’eau, de l’environnement et de l’énergie de l’Université<br />

Notre-Dame (WEERC-NDU), la fondation AVSI et l’Institut italien<br />

pour la coopération universitaire (ICU), étaient présents lors de cette<br />

conférence. Cette recherche pourrait permettre à l’avenir la mise en<br />

place d’une politique de préservation efficace des réserves d’eau dans<br />

cette région”.<br />

Et plus loin : A terme, les objectifs principaux de cette recherche<br />

sont multiples. Les scientifiques souhaitent constituer une base de<br />

données sur le versant de Nahr el-Kalb, pour pouvoir développer<br />

ultérieurement des projets d’infrastructure, visant à améliorer la gestion<br />

de l’eau.<br />

Il est regrettable que le <strong>Spéléo</strong>-<strong>Club</strong> <strong>du</strong> <strong>Liban</strong> n’ait point été<br />

présent à ce séminaire. Il aurait indiqué aux organisateurs de nombreux<br />

éléments concréts.<br />

A titre de rappel:<br />

a - Il avait été démontré dès 1923 qu’une partie des eaux <strong>du</strong> bassin<br />

versant <strong>du</strong> Kesrouan alimentait directement la rivière souterraine de<br />

Jiita, source principale <strong>du</strong> Nahr el Kelb (voir l’article intitulé ‘Les<br />

premiers traçage à l’uranine au <strong>Liban</strong>’).<br />

b - La revue libanaise de spéléologie et de karstologie <strong>du</strong> <strong>Spéléo</strong>-<br />

<strong>Club</strong> <strong>du</strong> <strong>Liban</strong> (<strong>Al</strong> Ouat’Ouate- Nouvelle série - N°3 - 1988 - pp. 3 à<br />

17- B. Hakim, J. Loiselet - G. Srouji - S. Karkabi) décrit précisément<br />

l’aspect spéléologique <strong>du</strong> cours d’eau souterrain, les<br />

traçages réalisés en amont et une carte hydrogéologique <strong>du</strong><br />

bassin versant <strong>du</strong> Nahr el-Kalb établie par le Dr Bahzad<br />

Hakim.<br />

c - La revue <strong>Al</strong> Ouat’Ouate N°4 - 1989, pp. 6 à 16<br />

fournie une étude faite sur 150 échantillons d’eau prélevés<br />

de 25 sources <strong>du</strong> Kesrouan sur une période de 9 mois. Ces<br />

échantillons furent soumis à des tests bactériologiques<br />

et physiques par le Professeur Joseph Hatem et M. Fady<br />

Chbatt M.S. Le nombre de sources contaminées s’est élevé<br />

à 84 %.<br />

d -A signaler aussi, qu’une reconnaissance nous a<br />

amené en 2007 sur les lieux de la coloration effectuée en<br />

1923 sur les ordres <strong>du</strong> Général Weygand. Nous avons pu<br />

localiser l’emplacement des pertes <strong>du</strong> Ouadi Bou Roqaa<br />

grâce au croquis N°1 établi par M. Odinot (géologue) et<br />

membre de la commission de la Cie des Eaux de Beyrouth.<br />

Le paysage est aujourd’hui entièrement bouleversé.<br />

De nombreux terrains des rives gauches et droites ont<br />

gagné sur le lit de la rivière.Terrains agricoles, maisons<br />

indivi<strong>du</strong>elles et immeubles ont été construits le long des<br />

berges. Nous avons pu toutefois repérer l’emplacement<br />

des gouffres <strong>du</strong> Moulin et celui <strong>du</strong> Platane. Ce dernier a<br />

été partiellement exploré et non topographié.<br />

Fig. 7<br />

En jaune sur le croquis, l’emplacement des pertes des gouffres <strong>du</strong><br />

Moulin et <strong>du</strong> Platane.<br />

Photo 1<br />

Terrain agricole amputant le cours d’eau.<br />

Des eaux usées se déversent à l’heure actuelle dans<br />

le cours principale de la rivière. Ces eaux se perdent en<br />

des fissures en aval <strong>du</strong> gouffre <strong>du</strong> Platane. Les marres<br />

rési<strong>du</strong>elles, la puanteur et les moustiques y habitent de<br />

concert. Les documents photographiques ci-joints illustrent<br />

cette catastrophe écologique.<br />

En conclusion : de graves problèmes de pollution<br />

apparaissent sur le bassin versant <strong>du</strong> Nahr el Kalb.<br />

Photo 2<br />

Constructions en bor<strong>du</strong>re <strong>du</strong> cours d’eau. Les eaux usées coulent à<br />

leurs pieds.<br />

Photo 3<br />

Marre stagnante et eaux usées dans le cours <strong>du</strong> Ouadi Bou Roqaa.<br />

Photo 4<br />

Le gouffre <strong>du</strong> Platane.<br />

20 | <strong>Al</strong>-Ouat ’Ouate 15 | 21<br />

Photo 5<br />

L’entrée <strong>du</strong> gouffre.<br />

LES PREMIERS TRAÇAGES<br />

À L’URANINE AU LIBAN

CAVE SURVEY Maïa Sarrouf | maiasarrouf@gmail.com<br />

ةقطنملا يف تلاكشتلا ىلع انعلطي لاقملا اذه<br />

تدمع .اتيعج ةراغم ىف رمحلأا رمملا تامسملا<br />

نافنص ىلإ تلاكشتلا هذه فينصت ىلع ةفلؤملا<br />

.رمحلأاو ضيبلأا ,امهنيب نوللا قراف ىلع ةدمتعم<br />

ROUGE SUR BLANC<br />

Une description des Galeries Rouges de Jiita<br />

Fig. 2<br />

Gours inondés dans la partie amont des Galeries.<br />

(Photo by Johnny Tawk)<br />

This article presents a general description of the Galeries Rouges’s concretions in Jiîta cave, visited<br />

<strong>du</strong>ring the <strong>Spéléo</strong> <strong>Club</strong> <strong>du</strong> <strong>Liban</strong> expeditions in 2007. The concretions are described according to the<br />

author’s vision who divided them into two categories, based on the striking contrast of white and red<br />

color found in the gallery.<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

Cet article présente une description<br />

générale des concrétions dans les Galeries<br />

Rouges de Jiita visitées en 2007, à l’occasion<br />

des expéditions organisées par le <strong>Spéléo</strong> <strong>Club</strong><br />

<strong>du</strong> <strong>Liban</strong>.<br />

LOCALISATION ET DESCRIPTION<br />

DES GALERIES ROUGES<br />

Les Galeries Rouges se trouvent sur la<br />

rive gauche de la rivière souterraine, à environ<br />

200 mètres en aval <strong>du</strong> siphon terminal. On y<br />

accède par un porche de moyenne dimension<br />

menant à une large salle d’effondrement.<br />

L’appellation des Galeries Rouges (1954)<br />

revient à la présence de concrétions<br />

particulièrement rougeâtres formées de<br />

dépôts d’argile et d’autres minéraux fortement<br />

calcifiés ornant l’ensemble des réseaux. Ces<br />

galeries se développent sur 140 mètres de<br />

long et se partage en deux sections ne se<br />

connectant pas (Fig. 1). La première est de<br />

direction E-O de 60 mètres de longueur, la<br />

seconde est de 80 mètres et son entrée se<br />

caractérise par une grande coulée de calcite<br />

révélant des concrétions riches et variées.<br />

Elle se termine par un large gour inondé. Sa<br />

topographie rejoint la tendance directionnelle<br />

<strong>du</strong> cours d’eau, NE-SO.<br />

A l’entrée des « Galeries Rouges », les<br />

spéléologues se déchaussent avant toute<br />

progression par souci de protection des<br />

fragiles formations calcaires.<br />

Les Galeries comprennent une variété<br />

de concrétions de calcite (stalagmites,<br />

stalactites, colonnes, draperies et coulées)<br />

ainsi que différents types de concrétions<br />

émanant de l’écoulement de l’eau sur le<br />

plancher (gours et micro-gours). Le contraste<br />

Fig. 1<br />

Topographie des Galeries Rouges de Jiita.<br />

qui existe entre ces deux types de concrétions<br />

blanchâtres et rougeâtres caractérise au<br />

mieux le charme de cet espace et a inspiré<br />

le titre de l’article (rouge sur blanc), dont la<br />

suite propose une description des différents<br />

spéléothèmes observés.<br />

CONCRETIONS DES GALERIES ROUGES<br />

Concrétions rougeâtres<br />

Le rouge caractérise par les gours qui<br />

ornent le plancher des couloirs. En amont,<br />

ces bassins naturels sont espacés (Fig. 2) et<br />

atteignent des profondeurs de 20 à 30 cm,<br />

tandis qu’en aval, ils montrent un festonnage<br />

plus régulier, concentré et moins profond<br />

(Fig. 3).<br />

Les plus grands gours (dont le gour<br />

terminal) comprennent des plans d’eau calme<br />

permettant le développement de calcite<br />

flottante (Fig. 4). Cette pellicule, rarement<br />

observée au <strong>Liban</strong>, est fragile et se précipite<br />

au fond de la vasque à la moindre secousse<br />

ou vibration. Les gours moins profonds sont<br />

généralement secs à l’étiage. Ils présentent de<br />

nombreux cristaux de calcite dans leurs parois<br />

internes ainsi que des formations no<strong>du</strong>laires<br />

sous forme de billes d’argile. Les bords<br />

externes de ces gours sont pour la plupart<br />

festonnés de micro gours (Fig. 4 et 5).<br />

Concrétions blanchâtres<br />

Les concrétions de calcite blanches des<br />

22 | <strong>Al</strong>-Ouat ’Ouate 15 | 23

Fig. 3<br />

Gours dans la partie aval des Galeries.<br />

(Photo by Johnny Tawk)<br />

Galeries tranchent avec les gours et le plancher stalagmitique de<br />

couleur rouge.<br />

Les draperies (Fig. 6) se développent sur les plafonds ou les<br />

paroisses inclinées et possèdent des dimensions variables de<br />

quelques mètres, atteignant 5 à 6 mètres de longueur.<br />

Les coulées sont assez répan<strong>du</strong>es au sein des Galeries.<br />

La forme la plus commune est celle des cascades (Fig. 7)<br />

retombant sur les gours gorgés d’eau et formant un clair<br />

contraste blanc sur rouge. Elles possèdent des tailles variant de<br />

2 et 5 mètres de long.<br />

Le mondmilch (formations blanchâtres) (Fig. 8), a été<br />

repéré sur la majorité des parois des Galeries surtout dans les<br />

branches comprenant les gours. Etant humides, ces formations<br />

étaient douces et plastiques lors de leur identification.<br />

Fig. 6<br />

Draperie au sein des Galeries.<br />

(Photo by Johnny Tawk)<br />

Fig. 4<br />

Calcite flottante et micro-gours sur le bord<br />

externe des gours.<br />

(Photo by Johnny Tawk)<br />

Fig. 7<br />

Calcite blanchâtre délicatement « coulée » sur les gours rougeâtres.<br />

(Photo by Johnny Tawk)<br />

.<br />

Fig. 5<br />

Formations no<strong>du</strong>laires dans le bord interne et micro-gours dans le<br />

bord externe des gours.<br />

(Photo by Johnny Tawk)<br />

Les stalagmites, stalactites et colonnes (Fig. 9, 10 & 11)<br />

sont de loin les plus communément observées et ornent le plafond<br />

et le plancher des Galeries. Certaines stalagmites et colonnes sont<br />

légèrement teintées aux couleurs de l’argile ou d’autres minéraux<br />

et pigments inorganiques.<br />

Des stalactites tubulaires sont de même observées. La<br />

Photo 12 illustre une stalactite tubulaire qui s’est jointe au micro<br />

gour <strong>du</strong> plancher formant une petite colonne d’environ 20 cm<br />

de longueur. Notons de plus, l’observation de stalactites dont<br />

la face externe est couverte de pointes cristallines, facilement<br />

assimilables à de minuscules excentriques et ne dépassant pas 2<br />

cm de long.<br />

Un type particulier de stalagmite est de même noté, celui<br />

des stalagmites d’argile (Fig. 13). Leurs dépôts sont associés aux<br />

Fig. 8<br />

Mondmilch sur les parois des couloirs.<br />

(Photo by Johnny Tawk)<br />

Fig. 9<br />

Massif stalagmite montrant à sa base le contraste<br />

blanc sur rouge marqué par le niveau de l’eau.<br />

(Photo by Johnny Tawk)<br />

Fig. 10<br />

Stalactite au sein des Galeries.<br />

(Photo by Johnny Tawk)<br />

changements dans la composition de l’eau d’écoulement.<br />

Leur morphologie est caractérisée par leur forme conique et par<br />

l’existence d’un cratère ou trou central. Au sein des Galeries, elles<br />

ne furent observées que dans les gours et ne possèdent pas plus de<br />

30 à 40 cm de haut, ne dépassant pas la hauteur des ces bassins<br />

étagés.<br />

CONCLUSION<br />

Un diagnostic aussi préliminaire des concrétions des Galeries<br />

Rouges permet de conclure que cette partie de la grotte mérite<br />

une attention particulière, formant une combinaison de tonalité<br />

et de richesse rare à observer. Des études plus approfondies<br />

sont recommandées pour tenter de comprendre la présence et la<br />

séquence de formation des concrétions.<br />

Fig. 12<br />

Petite colonne formée par la jointure d’une stalactite<br />

tubulaire aux micro-gours <strong>du</strong> plancher.<br />

(Photo by Johnny Tawk)<br />

Fig. 13<br />

Stalagmite d’argile à cratère central observé au sein des gours.<br />

(Photo by Johnny Tawk)<br />

Fig. 11<br />

Remarquable contraste formé par une colonne et des gours.<br />

(Photo by Johnny Tawk)<br />

RÉFÉRENCE<br />

Auteurs ayant travaillés sur des articles similaires:<br />

Bou Jaoude, I., Karanouh, R., 2002. Identification<br />

of Calcite Speleothems in Mgharet Nabaa el<br />

Shatawie. <strong>Al</strong>-Ouate’Ouate, 12 , 48-57.<br />

Bou Jawdeh, I., Karanouh, R., 2005. Photographic<br />

Documentation of Some Special Speleothems<br />

from Lebanon, <strong>Al</strong>-Ouate’Ouate, 13, 62-71.<br />

RECONNAISSANCE<br />

L’auteur remercie les contributions<br />

techniques, les commentaires et les avis de Sami<br />

Karkabi et de Issam Bou Jaoude.<br />

24 | <strong>Al</strong>-Ouat ’Ouate 15 | 25

CAVE SURVEY<br />

Fig. 1<br />

‘The Ballerina’ in Salle Beayno.<br />

(Photo by Issam bou Jaoude)<br />

Elias Labaki | e.labaki@gmail.com<br />

FINAL<br />

NOTES<br />

ON<br />

SALLE<br />

BEAYNO<br />

Samer harb | samaelh@hotmail.com<br />

ريبك ددعب رواغملا يف بيقنتلل ينانبللا يدانلا قفار اتيعج ةراغم نم ءزجلا اذه<br />

ام فاشتكا ةداعا ّمت نا دعب ىهتنا لمعلا نكلو .مرصنملا ماعلا يف تلاحرلا نم<br />

.اتيعج ةراغمل يلامجلاا لوطلا ىلا فاضي مقرلا اذهو تارمملا نم م 850 نع ديزي<br />

لاغشلاا هذه تقفار .ةراغملا نم ءزجلا اذهل قيقد روصم عضو يدانلا نوكي كلاذبو<br />

.لاقملا اذه يف بتاكلا اهيلا قرطتي ةقوشم ثادحاو تارماغم<br />

Après sa première visite, la salle Beayno a été réexplorée et retravaillée. Même<br />

si elle ne figurera plus dans nos prochaines sorties, elle laissera toujours dans<br />

notre mémoire tous les souvenirs d’une belle salle, là-haut, en passant par le<br />

boulevard SCL de Jiita.<br />

Fig. 2<br />

The large tunnel in Salle Beayno.<br />

(Photo by Issam Bou Joude)<br />

Fig. 3<br />

Mud stains on crystal white calcite a result of careless explorers.<br />

(Photo by Rena Karanouh)<br />

Salle Beayno…<br />

For the last year this name accompanied us in each and<br />

every Jiita trip, but now it’s over (Fig. 1, 2 and 3).<br />

The result: eight hundred and fifty-five meters of extra<br />

cave development to be added to the total development of Jiita cave<br />

with a fourth connection to the main Jiita axis; a new and more<br />

accurate survey is now finally completed (Fig. 4 and 5); and above<br />

all, lots and lots of adventures, stories and memories…<br />

We’re definitely going to miss the delightful climb up left<br />

after the SCL camp site, the opposition climb following that and<br />

finally the caving ladder, leading to a traverse line which leads in<br />

turn to a crawl, then a big chamber and a crawl and a… the point is<br />

that we spent memorable moments in gallery Beayno’s tunnels and<br />

chambers.<br />

Come to think of it, it was not long ago that we first<br />

decided to re-explore this section of our beloved mother of all<br />

caves, Jiita. The first trip to Salle Beayno took place in June of last<br />

year.<br />

During that outing, a small group of SCL cavers pointed<br />

out the discrepancies between the published map and the actual<br />

structure of the cave (Labaki and Harb, 2008).<br />

Salle Beayno had – again – its fair share of allotted time<br />

<strong>du</strong>ring the infamous three-day expedition trip in October 2007.<br />

The team spent a whole day exploring and surveying the galleries,<br />

except for the sinkholes which required dedicated equipment. These<br />

drops were later fully explored and drawn <strong>du</strong>ring a third trip.<br />

Two question marks remained on the survey map. Now,<br />

is it just me or are they really provoking…. those small question<br />