How Did Pictorialism Shape Photography and Photographers ?

The unsettling question about the legitimacy of photography as a genre of fine art is being posed over and over again for the last 200 years. Is photography really an art that deserves to be considered equally valuable as painting? Many contemporary art critics still disagree when it comes to this controversial question, posed for the first time in the early 19th century by the pictorialists. Pictorialism as an art movement was strongest from 1885 to 1915[1], but it kept being marginally active even in the 1940s, due to its alluring nature which kept being popular among the 20th-century photographers. While there is no precise definition of pictorialism, it is best described as a photographic approach focused on the beauty of subject matter and the perfection of composition rather than the documentation of the world as it is. Having this in mind, it is not strange that pictorialists were the first ones to think about the artistic value of photography in a rather serious way. They gave their very best to infuse a certain otherworldly feel into the previously non-romantic and starkly objective medium of photography.

Brief History of Pictorialism

Pictorialism owns its name to Henry Peach Robinson, British author of Pictorial Effect in Photography (1869), a book which remained one of the most influential 19th-century writings on photographic technicalities and aesthetics. Robinson’s main goal was to separate photography as an art form from photography used towards various scientific and documentary purposes.[2] Another British photographer from the same era, called Peter Henry Emerson, was also searching for the ways to emphasize the personal expression in photography rather than the mere objectivity. His works were dedicated mainly to capturing landscapes and recreating atmospheric effects in nature. However, it wasn’t until the early 1900s that pictorialism started to spread and gain its popularity. This happened thanks to the availability of early Kodak snapshot cameras as well as the efforts of Alfred Stieglitz, a famous American artist who gathered a group of fellow artists. The group created its own photographic movement called photo-secession and its primary goal was the promotion of photography as a medium which is as expressive and meaningful as painting. Stieglitz’s approach to photo imagery was the first of its kind since he was paying a lot of attention to composition, color, and tonality, always trying to capture something beyond the regular reality and closer to the realm of dreamlike. Together with other pictorialists such as Edward Steichen and Clarence White, Stieglitz has contributed to the radical change in the perception of photography and he has also prepared the ground for enormous sales of these otherworldly artworks, which took place over a hundred years later. Actually, one of the most important moments in the history of pictorialism happened in 1910, when the Albright Gallery in Buffalo bought 15 photographs from Stieglitz. This was the first time that a gallery recognized the value of photography and such approach initiated a powerful change which affected many art collectors and institutions.

Alternative Printing Processes in Pictorialist Photography

Pictorialists, unlike the majority of so-called straight photographers, were known for their meticulous experimentation with the most diverse printing processes. They used to begin their extensive processing with an ordinary glass-plate or negative but consequently they would stay focused on the choice of photo papers and chemical procedures capable of enhancing or reducing certain effects. For the same reason, some pictorialists were using special lenses to produce softer images, but the softening of focus during post-processing was certainly the most common practice. It is known that many of these revolutionary artists used rather alternative printing processes considered too complicated or simply unreliable by straight photographers. For instance, pictorialists were very fond of using gum bichromate – it was an unusual strategy which involved multiple layers of chemicals and resulted in a painterly image resembling watercolor paintings. Another favorite procedure of pictorialists was an oil print, which was quite useful since it allowed photographers to be selective and manipulate the lighter areas of print while keeping the darker parts intact. Besides these marginalized approaches, pictorialists used to rely on more common yet artistic enough practices, such as cyanotype or platinum print.

Taking Pictorialist Pictures - Famous Photographers

Even though early pioneers like William Henry Fox Talbot took “artistic” pictures of hay stalls, for instance, that perhaps could have been considered pictorialist because of their particular aesthetics, they were nevertheless proclaimed “documentary” - because photography was used to do just that, merely immortalize the things that are around us and nothing more. So when pictorialism, as a movement, proclaimed its goal to imitate art, it was a very tongue-in-cheek statement. Painters have already seen the photographic medium as a sworn enemy because it took the popularity away from them in the second half of the 19th century, and now it was trying to “steal” the artistic feel of their works as well. But photography was just trying to prove that, even though the camera provided great technical help in capturing images, it all still needed human intervention in order to be taken on the next level. The works of pictorialist photographers did intentionally look like paintings and charcoal drawings because they were desperate to be recognized as something more than just a click of the shutter - and eventually they were, thanks to their innovative creators.

Video - The Difference Between Pictorialists and Realist Photographers

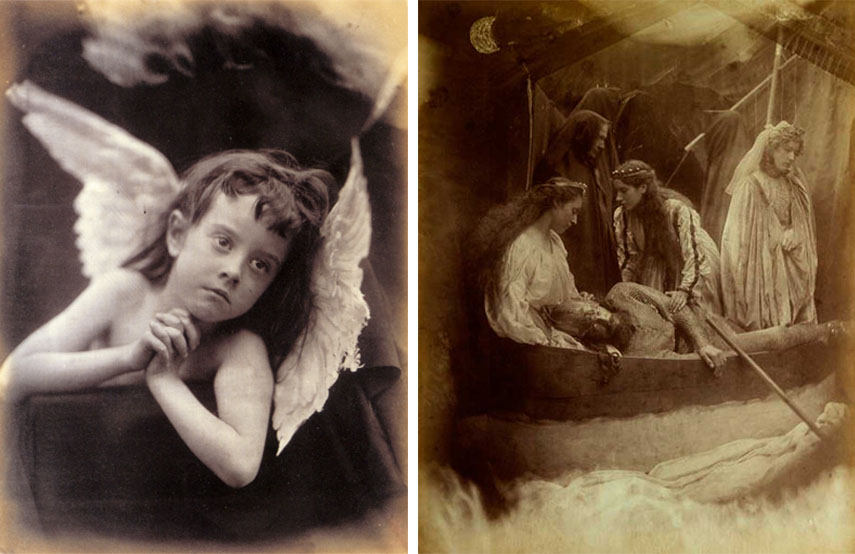

Julia Margaret Cameron

Introduced to the camera for the first time at the age of 48, Julia Margaret Cameron practiced photography for eleven years of her life in the mid-19th century, but her beautiful body of work wasn’t discovered until eighty years after her death. She was perhaps one of the very first practitioners of fine art photo-making, inspired by the pieces of famous painters to create non-commercial portrait art. Julia Margaret Cameron’s photos are visual poetry told about womanhood in the Victorian era and many of her pictorialism photographs were “staged” like in a movie set, either to serve as book illustrations or for pure personal pleasure. They ooze in innocence, youth, the kind of spirit that made her become one of the most important contributors to early Pictorialism and one of the most important artists in Britain at the time.

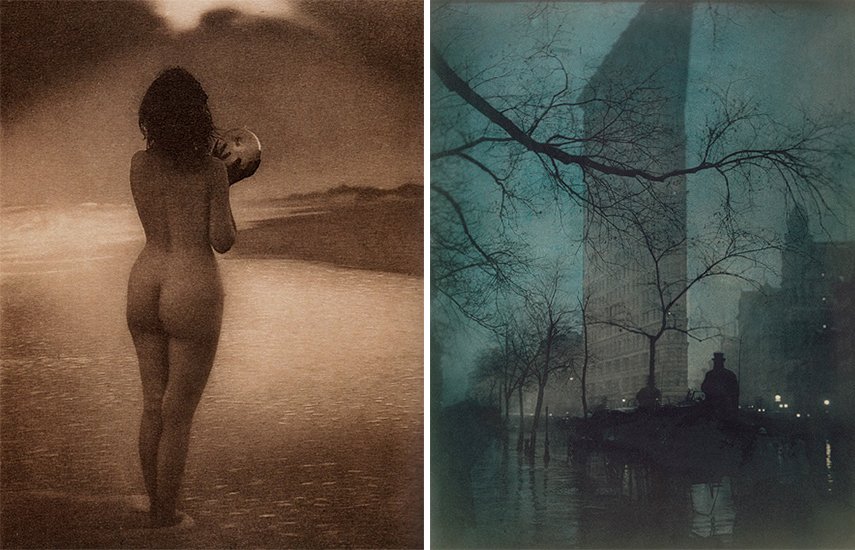

Robert Demachy

At first glance, the compositions of Robert Demachy look very much like charcoal drawings, but they are indeed photographs, intensely manipulated to produce such visual impact. A prominent pictorialist of the early 20th century, the French artist was also the director of the Photo-Club de Paris, the French parallel to the American Photo-Secession, as well as the Viennese Kleeblatt and the British Brotherhood of the Linked Ring. His pictorial photographs couldn’t be farther from snapshots as they were produced using revived non-standard photographic processes, such as the gum bichromate which let artists color and apply brushwork into the image. Robert Demachy also wrote extensively on photographic technique and aesthetics, including six books and more than one thousand articles.

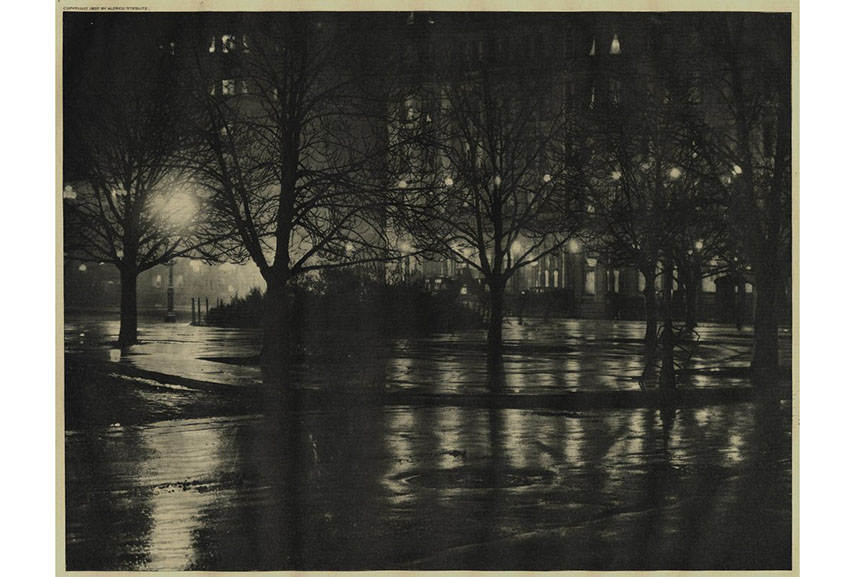

Alfred Stieglitz

He was a photographer, an art dealer, a publisher and a writer. Alfred Stieglitz surely is the most important figure in photography at the turn of the century. Thanks of his efforts, the medium of photography was raised to the status of art, both through his photos created from a view of a trained painter and Stieglitz role as the owner Camera Work magazine and the prominent 291 Gallery in New York, which promoted photo-secession with great dedication. Alfred Stieglitz strongly endorsed craftsmanship and rather than focusing only on producing his platinum prints in a certain way, he managed to obtain stunning visuals by incorporating elements like rain, snow and steam into his compositions, to create that true pictorial image that had great influence on the art world in general.

Edward Steichen

Photographer and painter, Edward Steichen was Alfred Stieglitz’s close collaborator and an influential modern artist. He too both practiced and promoted photo-making and became famous for his series of portraits of celebrities like J.P. Morgan in 1903. One of his best known prints is the 1904 The Pond - Moonlight, particular because of the simulation of color effect caused by laters of light-sensitive gums applied to the surface. Although Edward Steichen switched to realist photography after The Great War and even became the highest paid commercial photo-artist in the world, his pictorialist photography remains very influential. In part, it was inspired by Whistler’s Nocturne paintings, for instance, as well as the Japanese ukiyo-e prints. He was also Director of the Department of Photography at New York's MoMA.

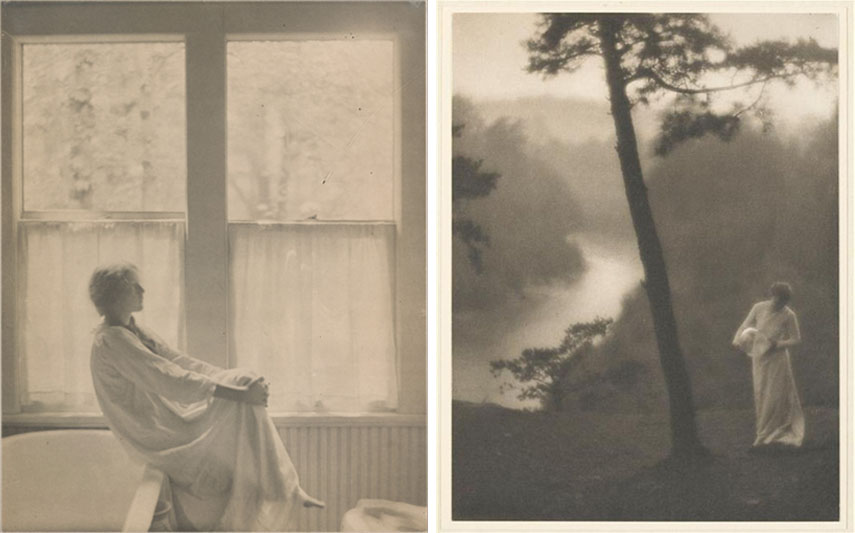

Clarence H. White

Another artist taking notes from famous painters was Clarence H. White, a teacher and one of the leading pictorialists. He was the creator of elegant, idyllic and intimate studies of friends and family, using natural light to evoke with a camera sentimentality in the spirit of Art Nouveau and Japanese art. He too was the founding member of Photo-Secession and in 1914 he also established the Clarence H. White School of Photography[3], the first educational institution in America to teach the wonders of the medium as a form of art. Until he died of a heart attack while teaching, he continued to promote artistic photography through lessons, exhibitions and associations with advertising art directors. His subtle lighting effects and gentle subject matter came to epitomize the Pictorialist approach and helped define great part of modern photography.

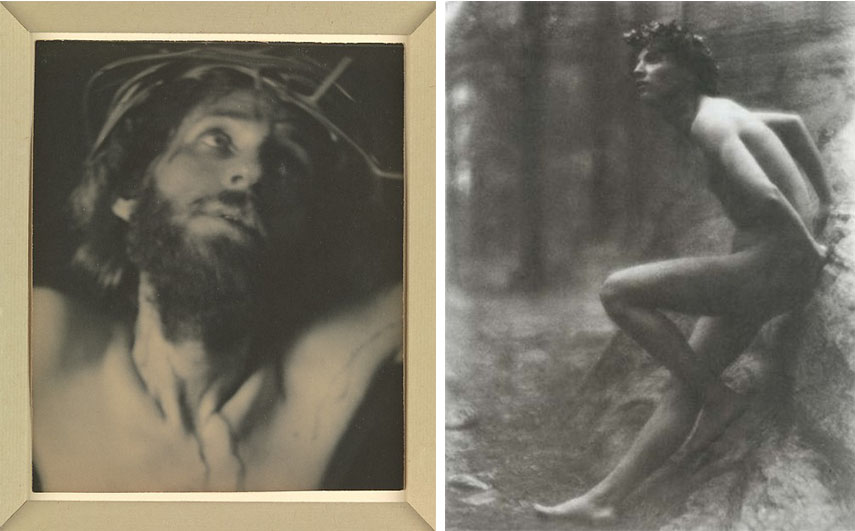

F. Holland Day

While other pioneers of pictorialism mostly photographed landscapes, F. Holland Day focused on portraiture and self-portraiture, and not just of any kind. In fact, he could be considered the father of conceptual art in photography in a way, as his works - and life - were quite controversial. His subjects were often nude young men in different settings and poses, and when he didn’t photograph others, he photographed himself, as none other than Jesus Christ. F. Holland Day made as many as 250 negatives showing scenes of the life of the Savior, from the Annunciation to the Resurrection, for which he starved himself, let his beard grow long and even imported cloth and a cross from Syria. According to The Met Museum[4], he used photography for sacred subjects as a matter of artistic freedom.

Adolph de Meyer

Dubbed by Cecil Beaton as “the Debussy of photography”, Adolph de Meyer was best known as the first official fashion photographer for the American magazine Vogue, for which he worked between 1913 and 1921. In fact, his dreamy, stunningly-lit works were created to better compliment his famous models, which included celebrities such as Ann Pennington, Irene Castle, Marilyn Miller, Luisa Casati and Queen Mary herself. Mysterious and extravagant, Adolph de Meyer produced imagery that much resembled portrait paintings of the Old Masters in some cases, setting the standards of elegance and class in fashion photography that would still matter much later on, even though his Pictorialist tendencies were, ironically, outmoded by the 1930s.

Gertrude Käsebier

Although she formally studied drawing and painting, Gertrude Käsebier was obsessed with photography, which eventually led her to become one of the first acclaimed and recognized female art photographers in history. She was very aware of this fact, as she encouraged other women to take up the technique as proper career, at a time when women didn’t even have the right to vote yet. During her long and productive life, she created many evocative images of motherhood, featuring her family and friends, as well as powerful portraits of Native Americans. Gertrude Käsebier was well-known within the circle of Pictorialists, having her work hanging in major exhibitions and even selling her work for as much as $100, a record which was not broken for the next fifty years.

Heinrich Kühn

Heinrich Kühn was described by The New York Times as ”one of the medium’s great control freaks”, mainly due to the routine he went through when taking pictures of his family.[5] He would sketch the site, pick clothing and poses and waited for the right lighting along with his models. Perhaps it is because of such dedication that he is also considered one of the most important Pictorialists out there, known for a body of work that closely resembles Impressionist paintings with its soft focus and tonality. Heinrich Kühn was also the inventor of several printing techniques, such as the Gummigravüre, which combined photogravure and gum bichromate, the Leimdruck, which uses animal glue, and the Syngraphie, which consists of two negatives of different sensitivity that provide larger tonal spectrum.

Alvin Langdon Coburn

Last but not least, we have the great Alvin Langdon Coburn, the icebreaker of many things in photography as medium and technique.[6] A curious experimenter, he was an accomplished photographer by the age of eight and his later style was influenced by the ink paintings of the Japanese master Sesshū. Upon his first discoveries in the field of non-objective photography, he started creating vortographs, as he called them, associating them with the English Vorticist group. In fact, Alvin Langdon Coburn was the first to deliver imagery that was completely abstract, and even after a short break from the camera between the mid-1920s and the 1950s, he continued to make mysteriously ambiguous photographs. He is also the author of the iconic portraits of Henry James and Auguste Rodin, both from 1906.

Long-Lasting Influence of Pictorialism

In the late 1920s, modernism was becoming prevalent and the appeal of pictorialism turned obsolete step by step, even though it never completely faded away. In fact, during the last 100 years, photography has gone through a significant shift in the way it is both created and perceived. Because of all the available technological advances, photography has become the most common artistic medium and all of its subcategories went through a certain revival or redefinition. Just like in the early 19th-century, we have to pose similar questions again, this time related to the meaning of artistic validity in mass production. Nowadays, we have a plenty of digital artists mimicking the work of pictorialists through the surreal portraiture and landscapes, but what is the real value of such works, no matter their growing popularity?

Neo-Pictorialism

Even though there are modern photographers who fall into a recently-coined category of neo-pictorialism, the emphasis of their work is simply on the aesthetics, without any engagement in the artistic activism which was crucial to the original photo-secession movement. However, thanks to those more traditional or perhaps more nostalgic artists among neo-pictorialists, there was a rise in alternative processes in the 60s and the 70s. For instance, Adolf Fassbender, a 20th-century photographer from Germany represented by prestigious Howard Greenberg gallery in NYC, kept making old-school pictorial photographs even in the late 1960s. Fassbender simply believed that pictorialism should last forever because it is based on universal beauty. "There is no solution in trying to eradicate pictorialism for one would then have to destroy idealism, sentiment and all sense of art and beauty", claimed the German artist.

Subtlety versus Manipulation

The resurrection of the pictorialism in the 1960s continued with the photo silk-screen techniques and finally culminated in the digitally-enhanced imagery, typical for the 21st century. The strong legacy of pictorialism can still be seen in many realms of photography nowadays – for instance, the poetic compositions which were once reserved for pictorialism can be found in documentary works of mainstream photographers such as Steve McCurry or even in high-end fashion portraiture. While it is true that digital manipulation has replaced some of the methods used back in the early 20th century and the majority of modern photographers are not proficient in the subtleties of traditional photographic processes, the human desire to celebrate all forms of beauty through perfectly composed dreamlike photos still remains. Perhaps Stieglitz, the father of pictorialism, explained it best when he said that "in photography there is a reality so subtle that it becomes more real than reality".

Written by Jacqueline Clyde and Angie Kordic.

Editors’ Tip: TruthBeauty: Pictorialism and the Photograph as Art, 1845-1945

TruthBeauty contains 121 stunning works by the form’s renowned artists, including Julia Margaret Cameron, Alvin Langdon Coburn, Robert Demachy, Peter Henry Emerson, Gertrude Käsebier, Heinrich Kühn and Alfred Stieglitz. Together, the collected works trace the evolution of Pictorialism over the three decades in which it predominated.This is the only collection of Pictorialist photographs by artists from North America, the United Kingdom, continental Europe, Japan and Australia in a single publication. Scholarly essays, and a selection of historic texts by Pictoralist artists, complete this rich overview of the first truly international art movement.

References:

- Anonymous, Pictorialism, Britannica

- Anonymous, Pictorialism and the Photo-Secession, Photogravure

- Hostetler L. (2004), International Pictorialism, The Metropolitan Museum

- Fulton M., Pictorialism into Modernism: The Clarence H. White School of Photography, Rizzoli International Publications, 1996

- Rosenberg K., An Early Adopter in Photography Meets the Big Shots, The New York Times

- Ankele, D., Ankele D., Alvin Langdon Coburn - Pictorialist Photography - Pictorialism, Ankele Publishing, LLC, 2011

Featured images in slider: Alvin Langdon Coburn - Brooklyn Bridge, 1911; Peter Henry Emerson - Life and Landscape on the Norfolk Broads, 1885-86; Robert Demachy - Speed, 1904. Captions, via Creative Commons; Gertrude Käsebier - Amos Two Bulls, Dakota Sioux, ca.1900. Captions, via Creative Commons; Edward Steichen - Balzac, The Silhouette, 4 A.M., 1908. All used for illustrative purposes only.

Can We Help?

Have a question or a technical issue? Want to learn more about our services to art dealers? Let us know and you'll hear from us within the next 24 hours.