When Britain announced it would supply Ukraine with depleted uranium rounds designed to penetrate tank armor, Russia decried the move as escalation. U.S. officials had a simple response: If you don’t like it, leave Ukraine.

What are depleted uranium rounds, and why is U.S. sending them to Ukraine?

On Wednesday, almost six months later, the United States announced it would follow Britain in supplying Ukraine with 120mm tank ammo made of depleted uranium, setting off another flurry of criticism from Russian officials who said the rounds could cause cancer and other illnesses.

Depleted uranium has been used in both antitank rounds and armor for years, particularly in the 1999 NATO bombing campaign in Kosovo, the 1991 Persian Gulf War and the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

Advocates against the substance’s use in conflicts have long argued that it can cause ecological damage and long-lasting health effects. In a statement, the International Coalition to Ban Uranium Weapons condemned the move to send the weapons to Ukraine, calling it “self-destructive and deceptive.”

“Like in the case of cluster munitions, the delivery of DU munitions is counter-productive and careless,” the statement read. “It adds to the war-related environmental burden of Ukraine, damaging its legal integrity as victim of aggression and illegal attacks.”

Although it is a byproduct of the process that creates enriched uranium that can be used in nuclear weapons, depleted uranium is sought not for its radioactivity, but for its extraordinary density, which makes it useful in armor and ammunition. Russian President Vladimir Putin nonetheless has argued that use of the munitions could constitute nuclear escalation.

The U.S. move to supply Ukraine with depleted uranium rounds comes after a controversial decision to provide cluster munitions, which human rights groups warn are predisposed to kill civilians because of their indiscriminate nature. Russia has been accused of using cluster munitions itself, as well as other taboo weapons such as white phosphorus munitions, an incendiary that can cause severe harm to civilians.

Depleted uranium

artillery rounds

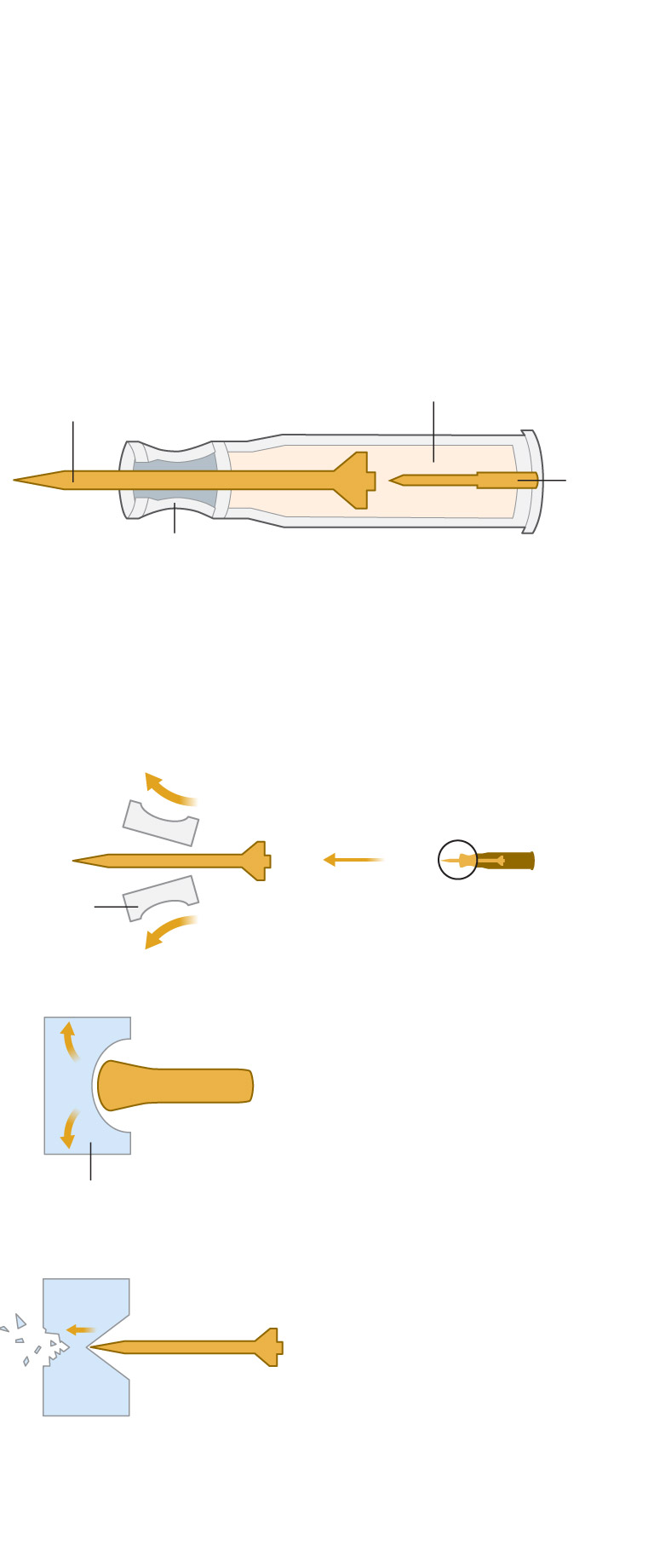

Russian President Vladimir Putin has said that the use of depleted uranium munitions, provided to Ukraine by Britain and now the United States, could lead to nuclear escalation. The rounds, however, are conventional projectiles, manufactured by both Russia and the United States. They are associated with heightened health concerns due to radiation and chemical toxicity.

Armor-piercing

projectile

Propellant charge

Sabot

(stabilizes the round

in the barrel)

Igniter

How uranium munitions work

After the projectile is fired, the sabot casing falls away.

Detail on

the left

Sabot

Standard steel armor-piercing projectiles tend to flatten as they strike armor plate, their kinetic energy spreading over a large area, potentially allowing the plate to withstand the blow.

Armor

Depleted uranium projectiles, because of the way their molecules bing together, tend to melt along their sides on impact, “self-sharpening” and spearing through armor plate in a deadly blast of molten metal.

Sources: Federation of American Scientists,

globalsecurity.org, U.S. Army

WILLIAM NEFF AND JÚLIA LEDUR/THE WASHINGTON POST

Depleted uranium artillery rounds

Russian President Vladimir Putin has said that the use of depleted uranium munitions, provided to Ukraine by Britain and now the United States, could lead to nuclear escalation. The rounds, however, are conventional projectiles, manufactured by both Russia and the United States. They are associated with heightened health concerns due to radiation and chemical toxicity.

Armor-piercing

projectile

Propellant charge

Igniter

Sabot

(stabilizes the round

in the barrel)

How uranium munitions work

After the projectile is fired, the sabot casing falls away.

Detail on

the left

Sabot

Standard steel armor-piercing projectiles tend to flatten as they strike armor plate, their kinetic energy spreading over a large area, potentially allowing the plate to withstand the blow.

Armor

Depleted uranium projectiles, because of the way their molecules bing together, tend to melt along their sides on impact, “self-sharpening” and spearing through armor plate in a deadly blast of molten metal.

Sources: Federation of American Scientists, globalsecurity.org, U.S. Army

WILLIAM NEFF AND JÚLIA LEDUR/THE WASHINGTON POST

Depleted uranium artillery rounds

Russian President Vladimir Putin has said that the use of depleted uranium munitions, provided to Ukraine by Britain and now the United States, could lead to nuclear escalation.

The rounds, however, are conventional projectiles, manufactured by both Russia and the United States. They are associated with heightened health concerns due to radiation and chemical toxicity.

Armor-piercing

projectile

Propellant charge

Igniter

Sabot

(stabilizes the round

in the barrel)

How uranium munitions work

After the projectile is fired, the sabot casing falls away.

Detail on

the left

Sabot

Standard steel armor-piercing projectiles tend to flatten as they strike armor plate, their kinetic energy spreading over a large area, potentially allowing the plate to withstand the blow.

Armor

Depleted uranium projectiles, because of the way their molecules bing together, tend to melt along their sides on impact, “self-sharpening” and spearing through armor plate in a deadly blast of molten metal.

Sources: Federation of American Scientists, globalsecurity.org, U.S. Army

WILLIAM NEFF AND JÚLIA LEDUR/THE WASHINGTON POST