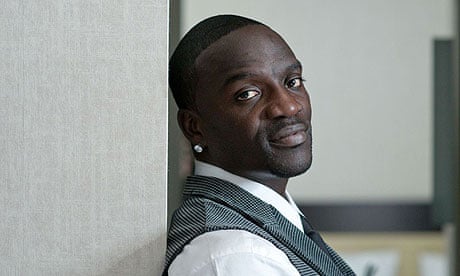

As it dawned in the early hours of November 5 that Barack Obama would be the next president of the United States, there will have been few citizens celebrating harder, or silently saying a more heartfelt prayer of thanksgiving, than the multi-million-selling R&B singer, producer, songwriter and label-owner Akon. Celebrities are known to say things in the heat of the pre-election moment that they will hope their fans (and detractors) will forget all about come the day of democratic judgement, but there was more than a hint of certitude about Akon as, sitting in a London hotel room eight days before America went to the polls, he outlined his plans for life under John McCain.

"It's funny," he said, "because I'm not the kind o' artist to really get into politics. But if he [Obama] doesn't get into office, I'm gonna change my citizenship. 'Cos I'm very afraid. I'm scared."

To what extent?

"To every extent!" He begins to chuckle. "Like, where are we now, if the people don't see it? That's a dangerous place to be next year. I'm literally movin' back to Africa. I'll just come visit, make some money and head back."

What, you have to wonder, is the Senegal-born star afraid of? A ratcheting up of racial tension? An escalation of wars that may help increase the risk of terrorist attacks? More Toby Keith albums?

"I can't even envision how bad it's gonna be," he sighs. "I see it now: just what we have had to go through in this past year. Like, I'm drivin' down the highway, I see cars parked with emergency lights on because they can't afford to buy gas. The shoulder lane has never been this full - you got families walkin' with kids in they hand, carryin' infants to the next exit to take a taxi, because the taxi get them home cheaper than the actual gas! That's crazy.

"No," he says, emphatically, shaking his head. "You think the crime rate is high now? Nah. I'll move me an' my family home. Seriously. I'm scared."

It's a surprising spiel from someone whose political songwriting is non-existent, unless you count tracks like his breakthrough hit, Locked Up, which was less social commentary than personal lament. Over the course of his brief but hugely successful career, Akon has become synonymous with the accessible end of hip-hop - with supplying hooks and hits that help rappers cross over into pop territory, and which have redrawn the boundaries of contemporary R&B.

Whether annoying or delighting in roughly equal measure with the speeded-up, Tweetie-Pie-on-helium UK No 1, Lonely, or duetting with Eminem on the smutty Smack That, Akon is many things, but challenging and politicised aren't among them. He and his associate, T-Pain, a key signing to

his Konvict Muzic label, have created a formula that has done more than cause everyone from Gwen Stefani to Michael Jackson to beat a path to the Atlanta-based maven's door. "That 808 clack, autotune sound," as he puts it, has become so ubiquitous that even those you'd think could beat the Konvict crew have decided to join them: Kanye West's current album owes a considerable debt, with the Chicago star claiming his take on the sound constitutes a new genre.

It seems an odd time for Akon to, as he puts it, "remodel the image", but that's precisely what he's done with a third album that makes two decisive breaks with his past. It all but abandons his sonic trademarks in favour of uptempo, club-inspired pop that puts him closer to Ne-Yo than any of the artists he's normally bracketed with, while its title breaks with his self-imposed nomenclature tradition. The first was called Trouble, the second Konvicted, but the previously announced Acquitted was retitled Freedom. Why?

Earlier this year, the US website The Smoking Gun published a 4,000-word investigation into Akon's claims - widely made during his meteoric rise to worldwide prominence - to have spent some years in prison as a result of a conviction for car theft. The website found several major discrepancies between the PR spiel - that his arrest and incarceration followed an FBI wiretap investigation into a car-stealing gang he ran in Atlanta in the 1990s - and the verifiable record. Notably, they could find evidence of only one six-month spell in jail, and an interview with the arresting officer elicited a derisive dismissal that Akon played a role in any auto-theft conspiracy. It was also pointed out that the date of birth of one of his children proved he couldn't have been in prison on at least one occasion when his biography implied he had been.

"Honestly? What they wrote was what I would have loved for my life to be," he smiles as he dances around the topic, preferring to despair at the website's motivation than attempt to explain what aspects of their story were wrong. "My whole argument was that if I did one day in jail or three years, it doesn't matter: it was that experience that changed my life for the better. They wrote it, people read it - whoever chooses to believe it, it's really on them.

"The whole purpose [of the Konvict brand and image] was to let everyone know, 'OK: this is who I used to be, and this is what I've become,'" he explains. "As time went by, I started to realise the misconception for those who didn't know the story; to them, it almost felt like we were promoting the convict thing, which wasn't the case whatsoever. When you use words like 'acquitted', it automatically gives you a negative vibe. So that's why we changed the title to Freedom, which means the exact same thing, but is more positive."

There is some substance to the defence that Akon eventually, and in fits and starts, manages to mount. He implies The Smoking Gun was unable to unearth his complete legal history because his real name and date of birth have not always been accurately recorded (it appears he was born Aliaune Thiam, but his name has appeared in versions up to 12 words long; and April 16 1973 is the most frequently reported of several different potential birth dates), and he refuses to give any definitive answers. He has routinely said he was born in Senegal and moved to America as a pre-teen, while The Smoking Gun claims he was born in the US. He says he has one felony to his name, from when police found a gun in a stolen car he was driving in New Jersey "around 2000". Yet trying to verify his version - or the website's - ends up posing yet more questions, criminal records searches unearthing only an unclear reference to a three-year sentence for a probation violation in Georgia in 1999, and a $10 speeding ticket in North Carolina.

It's hard to fathom Akon. He's clearly someone who enjoys spinning a yarn and watching it develop its own life - an interview technique used well over the years by everyone from Bob Dylan to the Beastie Boys. He may or may not have set out to mislead, but he has at the very least been complicit in his story being embellished. This shouldn't obscure the conspicuous good he's doing, whether it's through his charitable foundation, which is building its second school in Dakar, or in taking the kind of plunge less than a handful of American label-owners have dared, and signing a British rapper - fellow west African emigree, Sway - to a US deal. But the result is a confusion that risks undermining the credibility of the message it is his calling to deliver.

Akon believes, evidently sincerely, that his purpose beyond making music (and money) is to promote his redemption as an example. Yet curiously, it is to that figure in whom he has such a profound lack of faith - John McCain - that he turns for an explanation of why, in an era where models and actors eating insects is called "reality TV" and nations go to war over embellished research, all too often the truth is not enough.

"John McCain went to war. He was tortured. He experienced everything that a soldier would never want to experience," Akon says. "But at the same time, he's using that experience to gain votes. He brought it to the front so that people would vote for him. You wonder, like, 'Why would he do that?' And it's because he has to put them in the shoes that he was in to understand what he saw.

"If you tell someone something and they don't believe you, they're not gonna support it," he concludes. "So you have to pull out details that's shocking or something that they would actually have to imagine and close their eyes and be like, 'Ooh, I would never wanna have to go through that,' for them to actually understand. The drama of it is what makes it real."