Charlie Sheen and his ever-present entourage are taking a cigarette break outside their London hotel and I’ve tagged along for the ride. Such is Sheen’s reputation that just standing next to him on the pavement sounds as if it might be an experience.

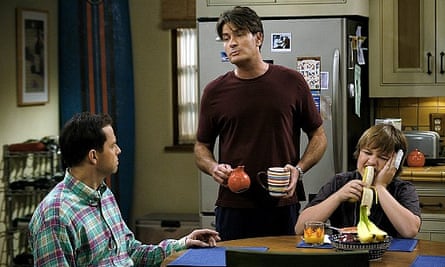

Sheen is in London because he is promoting a luxury condom. Whether the world needs a luxury condom is debatable; that Sheen needs whatever work he can get is not. Once the highest paid TV star in the world, Sheen has blown through his cash like he’s blown through his luck. He was born into an acting dynasty and further doubly blessed with genuine comedic talent and scene-stealing charisma. But by 2012, after 35 years of being given endless second chances by the TV and movie industries, happy to forgive accusations of spousal abuse and drug addiction as long as he brought in the fans, he finally made himself pretty much unemployable after his notorious meltdown during his departure from the sitcom Two and a Half Men.

Sheen was one of the very few 80s teen actors to have parlayed his youthful success into a longterm career, and the former star of Platoon and Wall Street once looked destined for Oscars glory. It takes serious effort to spunk away a life as gilded as Sheen’s, but spunk it he most certainly did. Then, last year, after months of rumours, he announced in a TV interview that he is HIV positive.

So here we are today, on a corner in Mayfair, talking condoms. And fair play to the man, whatever financial incentives he is getting aside, for using what he calls “my story” to promote safe sex. But he doesn’t always quite stay on message.

“Do you know a Jess?” Sheen asks me with his familiar wolfish grin.

No.

“Reality TV star,” adds an older man called Cooper, who is variously introduced to me as Sheen’s “best friend” and his “bodyguard”.

No.

“She was at the launch party [for the condom] last night, and now – now all the tabloids are saying we’re together!” Sheen says, eyebrows raised in bewilderment.

Welcome to the British tabloids, I say, thinking he is cross about this rumour. My thinking is wrong.

“No! It’s the one time I wanted the story to be true!” he cries. “But I’m the fucking Aids guy, so what am I going to say? ‘Come to the hotel and have a scone?’ It’s shit city, man. What’s my opening line? ‘Wanna come up and risk your life?’”

Sheen has apparently forgotten he’s supposed to be fronting a condom. But he’s got into his theme. He is, he explains, going through “kind of a drought at the moment”.

Well, you’ve banked a lot of non-drought moments, I say. Sheen has claimed to have slept with more than 5,000 women and he admitted to being a client of Heidi Fleiss’s prostitution ring in the 90s.

The smile returns. “You’re very sweet, thank you,” he says squeezing my arm, although I hadn’t exactly meant it as a compliment.

He and Cooper then talk about other events at the launch party last night, mainly involving Sheen inviting some women to dinner who Cooper didn’t think should come. There was some quarrelling.

Being Charlie Sheen sounds like a full-time job, I say.

Sheen doesn’t say anything. Cooper makes a big smile: “Naw, usually it’s great!”

I’ll be honest, it does not look great. It looks exhaustingly chaotic. But not as exhausting as working with him must be. By the time I finally meet him, my interview has been put back by a day and a half. Sheen’s people insist the delays are because he didn’t know there was an interview; other people whisper “hangover”. Sheen insists he is simply “jetlagged. I’m tired like a bitch! Sorry, I shouldn’t say that to a lady – I’m tired like an ass.” Initially, I was told I could ask him “anything” but the increasingly nervous PR suggests I don’t ask about “the past” or “too much about HIV”. Two days earlier, I’m told in a hushed tone, he reduced two journalists in Sweden to tears for focusing too much on the wrong things. The past and the present, presumably.

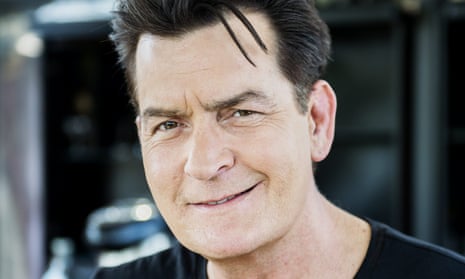

But on good days Sheen’s affability is in inverse correlation to his reliability, and he has cheered up by the time we meet, perhaps due to the faint smell of alcohol on his breath. He has given up the drugs, he says, but not the booze, although he’s “a sipper, not a drinker”. He is back under medical supervision after briefly abandoning his antiretroviral treatment medication to be treated by a man in Mexico, who claimed he could cure HIV with the milk of arthritic goats. Even Sheen eventually realised this was a terrible idea and returned to more conventional treatment. Nonetheless, today he looks shockingly (if not surprisingly) terrible. Still only 50, he is silver tongued and (mostly) focused but he has the hunched gait of a man 20 years older. The Sheen/Estevez men have excellent genes: his father, Martin Sheen, 75, and brother, Emilio Estevez, 54, still look terrific. But there’s only so much a body can take and the decades of substance abuse are written all over his hollowed face and busted body. The beautiful boy who 30 years ago stole the whole of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off in one scene when he played, appropriately, an eloquent drug addict now looks like the ghost of an old man. But you only need to spend a few moments in Sheen’s company to see how he got away with it for so long.

Even at his most out of control in 2011-12, when he made rambling threats against Chuck Lorre, the producer of Two and a Half Men, and insisted he was filled with “tiger blood”, he maintained an eloquence and sense of humour that made him far more compelling than the usual strung-out celebrity.

“People are thinking you gotta be on drugs,” a TV journalist said to him in 2012.

“Sure, I am on a drug and it’s called Charlie Sheen,” he replied, jittery but with a self-mocking grin. “It’s not available because if you try it once you might die and your face will melt off and your children will weep over your exploded body. Too much?”

He’s still bleakly amusing. The day before our interview, he is dragged out to a press conference for Lelo Hex luxury condoms and, while the executives drone on about how their prophylactic will change the world, Sheen mugs towards the audience like the sitcom pro he is.

“How’s your love life, Charlie?” a journalist asks.

“Right now I couldn’t get laid in a woman’s prison with a handful of condoms,” he replies, to the executives’ horror.

But what Sheen really has in spades is charm. He is unfailingly polite to me, making a big show of chivalrous gestures such as holding the door and complimenting my shoes. He is solicitous in thanking me whenever I mention a movie or TV show of his I enjoyed, of which there were many: the 80s dramas including Platoon and Wall Street, of course, but I always preferred the comedies. He was terrific in the sitcom Spin City, taking over from Michael J Fox when the latter’s Parkinson’s became too severe, and there is no doubt he completely carried Two and a Half Men. He’s such the gentleman one could forget that he has a long history of abuse towards women, and that both his ex-wives, Brooke Mueller and Denise Richards, alleged he threatened their lives. Sheen describes himself as “passionate”, not angry: “People tell me I’m bipolar and I’m like, go fuck yourself,” he adds. Anyway he says, more calmly, these days his focus is on “my health and my family.”

Does he think that his talent and eloquence ultimately worked against him, because he was able to behave badly for so long without any repercussions?

“It did become a mutual thing, yeah, but I don’t have to do that any more. I’m out of things to prove. I just want my kids to be proud of me when I’m here and when I’m gone. You know?”

Sheen has five children with three women, ranging in age from seven to 31, and he loves to talk about them, stopping only to bask in what he thinks is the adoration of approaching fans but what looks to me more like voyeurism. As we walk back into the hotel he urges me to write about how many people approached him outside. Doesn’t he get sick of it after 35 years?

“No! It’s an honour! Sure, it’s tiring, but you don’t worry about that. You worry about the day it stops.”

Given how much value he places on public adoration he must have been terrified about telling the world he is HIV positive. He insists he was “relieved”, but he spent “millions” over the years trying to keep it a secret when people were blackmailing him with exposure. After all, so much of his appeal lay in his fans living vicariously through him and, as he admits, “people want to be like me, but perhaps now not all parts of me”.

I went to the first night in Detroit of his infamous Violent Torpedo of Truth/Defeat is Not an Option tour in 2011, in which Sheen toured America to deliver his rambling rants in person. I’d assumed in retrospect the tour was a nervous breakdown in reaction to his HIV diagnosis but he says that came a month later: “That was that next moment of reality. I know, I was talking about ‘tiger blood’, but that was just a cosmic collision coincidence, the triple c,” he says.

Sheen himself was a wreck on stage, but I found the audience more depressing. They didn’t seem to understand the difference between the visibly intoxicated man on stage and the characters he played, and they booed him for not being funny enough.

Does he think people’s expectations of him exacerbated his behaviour off screen?

“I think, yes, yes, it led me to being something I wasn’t. I guess it comes down to a measure of people pleasing,” he says.

It is true that Sheen was promoted by Hollywood from the start as a “bad boy”, so he probably did feel compelled to live up to the image. But surely he can admit that his problems stem from him being so self-destructive?

“Not any more, because that prophesy will self-fulfil and it’s also sort of linked to my condition. There were just a couple times I didn’t practise [safe sex] and you might think, that kind of thing only happens to others. But that’s not my future any more. Which sucks!”

Martin Sheen has been touchingly vocal about his concern for his youngest son in recent years. Emilio Estevez, meanwhile, has given interviews in which he has suggested their upbringing was chaotic and their father had a heart attack on the set of Apocalypse Now at the age of 36, brought on by alcohol and stress. One of the nicest things, though, about Charlie Sheen is how close he has always been to his parents and siblings, frequently involving them in his work (aside from Emilio, he has an older brother Ramon and a younger sister Renée). When he went to the doctor to get the results of his HIV test in May 2011 at the age of 46, he took, heartbreakingly, his mother.

Was it harder telling his dad or his oldest daughter, Cassandra? (He says he hasn’t told his four younger ones yet.)

“My daughter, yeah, for sure. I called in on her on my way [to the TV interview in which he revealed his condition]. She was crying but I said: ‘I got this, OK? I GOT IT. We’re tough, OK?’ And we high-fived and hugged it out.”

How about your dad? The notorious temper that he has been trying so hard to tamp down suddenly flashes up at the memory: “Aww, he was giving me shit about going to AA, right? And I was like, ‘Here’s a thought, you want to talk about a real disease?’ And that’s when I told him. I was like, ‘Don’t talk about theories, I can show you bloodwork.’”

If any parent needs an argument to not put their kids on stage, that reason is Charlie Sheen.

This leads me to a question I’ve long wondered: why Sheen chose his father’s stage name when he started acting. He was born Carlos Estevez and his father, born Ramon Estevez, worked under the name of Martin Sheen because he simply couldn’t get any work in Hollywood in the 1950s with such an obviously Spanish name. Martin Sheen has since said that changing his name for work is “one of my big regrets, I know it really bothered my Dad”, and he frequently emphasises he is still legally Ramon Estevez. Sheen, however, is Charlie Sheen on his passport and driving licence, and his children, he says proudly, are “the first legal Sheens”. I’d long suspected that he wanted to make sure people knew he came from famous stock, an insecure bleat of “Don’t you know who my dad is?” by name, despite his obviously complicated feelings towards him. But he denies that: “I thought, given what Dad had done and did do for so many years, someone should perpetuate and prolong the name Sheen.”

So it was about paying respect to your father?

“Absolutely. Also, Charlie Sheen just sounds better than Charlie Estevez,” he says.

Nonetheless, Sheen’s tendency in the past to mock other people with ethnic names – referring to Barack Obama as “Barry Satera Kenya” in a tweet, and calling the Jewish Chuck Lorre “Chaim Levine” – suggests to me some self-loathing.

When I ask about his regrets, the first thing he says is, astonishingly, “I should have left Two and a Half Men better” – not being more diligent about practising safe sex, not falling into drug addiction. But Sheen desperately misses acting, he says, and I suspect he knows that, despite his talent and decades of work, casting directors now see him more as a C-list gossip item than an actor. For all his insistence that he has changed and matured, he is obviously still a nightmare to deal with, but it would take a cold heart not to feel very sorry for him now. He says he’s currently working on a frankly bewildering-sounding movie with Whoopi Goldberg about 9/11 and we’re just starting to talk about his 9/11 truther theories (“I mean, how could you not believe them?”) when his manager instructs me time is up.

“Come to dinner with us!” Sheen cries.

“That is definitely not happening,” his manager says firmly.

“No?” he asks plaintively.

“No,” his manager repeats.

Sheen shrugs sadly and once we stand up I realise he’s waiting for me to give him a hug. So I give him one.

“Are you scared?” I ask.

“No!” he cries, reeling back at the idea. Instead, he’s focusing on “owning my part and being mature and responsible and at times awesome”, he says with a smile. But he looks none of those things and the smile is empty.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion