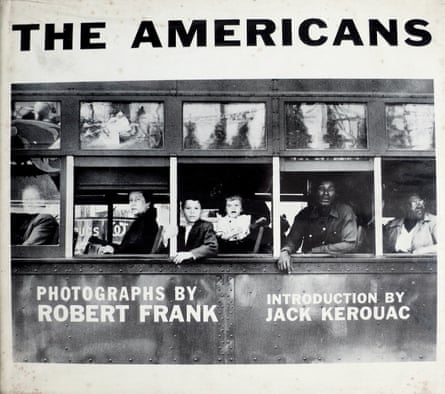

“A degradation of a nation,” is how Minor White described Robert Frank’s seminal masterpiece, The Americans. The renowned photographer and Aperture magazine editor wasn’t alone in his disdain, joining the editors of Popular Photography, who called it, “a wart-covered picture of America by a joyless man”. According to Frank, not even MoMA would sell the book, despite the fact their photography department was headed by one of his mentors, Edward Steichen. As a result, the book quickly went out of print after selling only 1,100 copies.

“It caught people off guard,” says Christopher Mahoney of Sotheby’s, which will auction 77 of the 83 photos in the book on Thursday in New York. “It’s always interesting to look back at initial critical reactions. One could make a long list of things that were lambasted when they came out and ultimately became a crucial component of the culture.”

The 1950s were boom time in America, as the nation emerged from the second world war a global superpower. Television, technicolor movies and rock’n’roll transmitted a fun-loving image of peace and prosperity, despite grassroots rumblings suggesting racism, poverty and despair. This hidden America was the one Frank aimed to capture when he set out in 1955 on a series of road trips that would eventually cover 10,000 miles and 30 states in nine months.

Years earlier, Steichen had seen promise in the young photographer who had only recently arrived in New York from his native Switzerland in 1947. Frank quickly found success in the trade, while shooting his own images on the side, and Steichen helped arrange exhibition space as well as assist with applications for the Guggenheim fellowship that eventually financed Frank’s fateful road trip. Frank’s application was also supported by Walker Evans whose 1938 publication, American Photographs, was a similar documentary series shot in the conventions of the era, albeit more observational than Frank’s sensual aesthetic.

What outraged critics at the time would barely raise an eyebrow today – a cowboy pausing to roll a cigarette in midtown Manhattan, a short-order cook glancing over her shoulder, a guy in a bar as he studies the options on a jukebox with an empty dance floor sprawling behind him. Sticking mainly to luncheonettes, public parks, roadside bars and factories, Frank photographed average people doing average things. Sometimes he shot surreptitiously, other times in low light with truncated figures, boiling grain, uneven horizon lines that dip to the right, suggesting he held the camera with one hand. The look breaks the conventions of acceptable photojournalism, and is a visual counterpart to the beat poetry of the day (Jack Kerouak wrote the book’s foreword). But Frank’s style became de rigueur, so ubiquitous today that it’s often taken for granted.

Frank’s legacy can be seen in just about every street photographer that followed, as well contemporaries like Garry Winogrand and Bruce Davidson, whose 1959 series on a Brooklyn street gang suggests a strong influence. “It didn’t hit me politically, it was lyrical, it was poetic and it was interesting and it was true. And it was an amazing body of work,” says Davidson of The Americans. “Even then, I was a little afraid of it. It was really America in the rough. It was an America we refused to look at.”

Davidson met Frank in the Bowery on the set of his film-making debut, Pull My Daisy. “I had a copy of Zoom magazine, which had the complete Brooklyn gang series,” says Davidson. Frank looked at the photos, gave him a pat on the back and sent him on his way. “That little slap on the back when I was 25 years old from Robert Frank meant a lot to me at the time.”

By then, Frank had largely moved on from photography, making movies like the abovementioned with many of his beatnik friends, as well as the little-seen Rolling Stones documentary, Cocksucker Blues, which the band themselves suppressed due to its unguarded footage of backstage drug use and groupie shenanigans. Frank still worked in photography and was finally able to sell some of his work (as opposed to his services), when the art market in photos began to take hold.

“It was really only beginning in the 1970s that Frank was able to actually make a certain amount of money, and it wasn’t a heck of a lot of money. So his opportunities and reasons for making prints prior to that point were incredibly limited,” says Mahoney, adding that the original negatives are in storage at the National Gallery. It appears that Frank is no longer printing from them. And while there remains no firm number on the amount of images made, practice and experience indicate a limited few.

The 77 prints going to auction are from the Ruth and Jake Bloom collection, compiled over more than 20 years. They were struck directly from the artist’s negatives, either by Frank or under his supervision, and each is signed. Like many photographers of his generation, Frank didn’t print in editions, which makes it difficult to gauge how many actually exist. As a result, Sotheby’s makes their evaluation based on what has appeared on the market in the past and what is known to exist in other collections.

An exception is lot 42, Frogmore (Funeral – St. Helena, South Carolina), depicting three African-American mourners leaning against some parked cars, which has likely never appeared at auction. “That doesn’t mean this is the only print ever,” Mahoney clarifies, about the artwork, which has a suggested price of $35,000 to $50,000. “It means this is your first opportunity to get this photograph, to bid for it at auction. There are a number of prints that fall into that category.”

They include lot five, NYC (Bar – New York City), featuring a glowing jukebox with a couple occupying a booth in the background, suggested at $25,000 to $35,000, as well as the classic, Miami Beach Hotel (Elevator), which depicts a harried-looking hotel staffer of whom Kerouac wrote, “That little ole lonely elevator girl looking up sighing in an elevator full of blurred demons, what’s her name & address?” It is expected to fetch $150,000 to $250,000.

“He drove across the country several times, made innumerable side trips and managed to avoid the tourist places,” says Mahoney, putting the lie to the notion that it took an outsider from Switzerland to present an image of America its citizens found so alienating. “If Frank had been born in Hoboken, he would have been just as much an outsider. Could this book have been made by an American photographer? Absolutely. It just happened not to have been. It depicted an America that most people didn’t realise existed, although it was right there in front of everybody.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion