Robert Frank is 90 years old on Sunday. The great pioneer and iconoclast has become a survivor, celebrated and revered, but still resolutely an outsider. One thing we can be sure of: he won’t be looking back.

“The kind of photography I did is gone. It’s old,” he told me without a trace of regret in 2004, when I visited him at his spartan apartment in Bleecker Street, New York, where a single bread roll and a mobile phone the size of a brick sat forlornly on the kitchen table. “There’s no point in it any more for me, and I get no satisfaction from trying to do it. There are too many pictures now. It’s overwhelming. A flood of images that passes by, and says, ‘why should we remember anything?’ There is too much to remember now, too much to take in.”

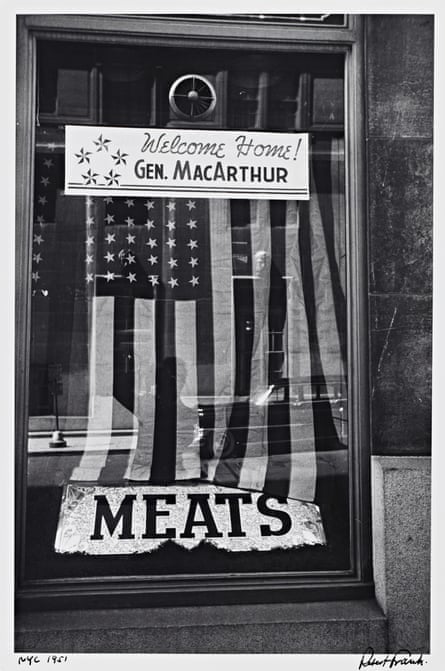

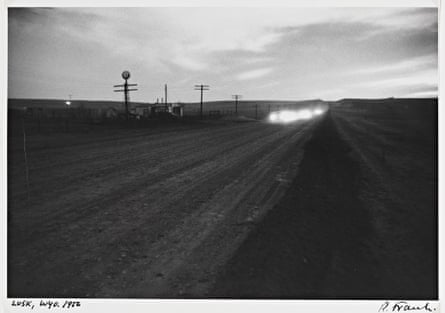

Nevertheless, it is impossible to imagine photography’s recent past and overwhelmingly confusing present without his lingeringly pervasive presence. Frank was 31 in 1955 when he secured the Guggenheim Grant that financed his various road trips across America the following year with his wife and his two young children in tow. He shot around 28,000 pictures. When Les Americains was published by Robert Delpire in France in 1958, it consisted of just 83 black and white images, but it changed the nature of photography, what it could say and how it could say it. Published in the United Sates as The Americans by Grove Press a year later, it remains perhaps the most influential photography book of the 20th century.

“I had Robert Frank’s The Americans as a teenager,” Jeff Wall told me recently, describing the early epiphany that led him into elaborately-staged art photography. “In fact, I made pencil drawings from various photographs in it. Frank and Walker Evans closed the door for me. What they did was so well done, I could never have matched it and I don’t think anyone has. They nailed it once and for all. That was a huge realisation – that I could not follow in their footsteps.”

The artist Ed Ruscha related a similar story. “Seeing The Americans in a college bookshop was a stunning, ground-trembling experience for me. But I realised this man’s achievement could not be mined or imitated in any way, because he had already done it, sewn it up and gone home. What I was left with was the vapours of his talent. I had to make my own kind of art. But wow! The Americans!”

The Americans challenged all the formal rules laid down by Henri Cartier-Bresson

and Walker Evans, whose work Frank admired but saw no reason to emulate. More provocatively, it flew in the face of the wholesome pictorialism and heartfelt photojournalism of American magazines like Life and Time. The Americans was shocking – and enduringly influential – because it simply showed things as they were. “I was tired of romanticism,” Frank told me, “I wanted to present what I saw, pure and simple.”

Frank’s America is a place of shadows, real and metaphorical. His Americans look furtive, lonely, suspicious. He caught what Diane Arbus called the “hollowness” at the heart of many American lives, the chasm between the American dream and the everyday reality. With his handheld camera, Frank embraced movement and tilt and grain. Contemporary critics reacted with a mixture of scorn and outrage, accusing him of being anti-American as well as anti-photography. A review in Practical Photography dismissed the book’s “meaningless blur, grain, muddy exposures, drunken horizons and general sloppiness”. The Americans portrayed a place and a people that many Americans just could not, or did not want to see: a sad, hard, divided country that seemed essentially melancholic rather than heroic. As Jack Kerouac put it in his famous introduction, Robert Frank “sucked a sad poem out of America.”

Frank was an outsider by temperament and design. Born and raised in Zurich, where he trained as a commercial studio photographer, he fled his solidly bourgeois family in 1947, tired of “the smallness of Switzerland”. In New York, he landed a job at Harper’s Bazaar, where famed art director, Alexey Brodivitch, had hired the likes of Cartier-Bresson and Bill Brandt, but deadlines and the dictates of magazine work quickly wore him down and he set off for South America, shooting in the towns and villages of Bolivia and Peru and living hand to mouth.

These journeys set the tone for much of what was to follow as Frank traveled through England and Wales before embarking on his road trips across America. Though he rejected Walker Evan’s more formal approach, he learned much from the older photographer, whom he accompanied on shorter trips after they met and became friends in New York. Their differing attitudes to photography – and to life – were essentially generational: the impeccably well-bred Evans once asked Frank, “Why do you hang out with those people, Robert? They have no class.” He was referring to Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, whom Frank had recognised as fellow iconoclasts in search of another wilder America that matched their outlaw imaginations.

Their influence would seep into Frank’s later work like a virus: the freeform flow of his fly-on-the-wall short films and the uncompromising diaristic style of the infamous Cocksucker Blues, a documentary about the Rolling Stones 1972 tour of America that caught the boredom and dissolution of life on the road in a grainy verite style that was way too revealing for the group. They sued to prevent its release and sent a sheriff to his door to confiscate his copy of the film. Legend has it that Mick Jagger acknowledged the film’s greatness but told Frank: “If it shows in America we’ll never be allowed in the country again.”

Ever restless, Frank abandoned photography for film in the early 1970s only to return to it a few years later in the wake of great personal tragedy. His daughter, Andrea, was killed, aged 20, in a plane crash in Guatemala in 1974. She had appeared alongside her brother Pablo in Frank’s confessional 1969 film Conversations in Vermont, two children of unconventional parents stranded in a progressive boarding school. (Pablo took his own life in 1994 after a long struggle with schizophrenia.) It is Andrea who haunts the photographs that Frank made in the 70s when he remade himself once again as an artist, often scratching or writing on the surface of his prints and Polaroids.

In one powerful dual image made in 1978 and taken though a smudged windowpane, his hand holds a small stick-like doll against a tilted horizon where a grey sea meets a grey sky. Beneath, a mirror reflecting only emptiness leans against the same window pane. Across both images, the words Sick of Goodby’s are smeared as if in blood. For all its staging, it is a viscerally powerful evocation of raw emotion: a cry of pure loss. It was one of Lou Reed’s favourite photographs.

“Robert Frank has been there, and seen that,” he wrote in 2004, “and recorded it with such subtlety that we only look in awe, our own hearts beating with the memories of lost partners and songs … Robert Frank is a great democrat. We’re all in these photos. Paint dripping from a mirror like blood. I’m sick of goodbyes. And aren’t we all, but it’s nice to see it said.”

When I asked Robert Frank about Sick of Goodby’s, he said that, after his daughter’s death, his work had “shifted from being about what I saw to what I felt”. He added, “I was really destroying the picture. I didn’t believe in the beauty of a photograph anymore.” Perhaps, though, he never really had and that is where the real and enduring power of The Americans resides – in the cold, hard truth of his outsider’s gaze. Or as Kerouac put it back then, “To Robert Frank, I now give this message: You got eyes.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion