The Perversity of Aubrey Beardsley

Beardsley was a precocious child and remained one, said Oscar Wilde, until he died at the early age of twenty-five. In this fascinating examination of a singular artist, the talented British novelist and essayist Brigid Brophy finds that “the genius of Beardsley’s eroticism is precisely the quality Freud ascribed to the sexuality of children Since the publication of her prizewinning novel, HACKENFELLER’S APE, in 1953, Miss Brophy has won honors and praise for seven more books. Her next, a collection entitled THE BURGLAR, will be published in May by Henry Holt.

BRIGID BROPHY

To SPEAK of a Beardsley revival, whose beginning one would have to date somewhere about 1963 or 1964, could easily be an exaggeration. Aubrey Beardsley has been and to some extent still is slighted, but he has never in fact been forgotten since the day in 1898, a fortnight after his death, that the New York Times declared his work “already . . . well-nigh forgotten.”

In England much of Beardsley’s work was reprinted after the Second World War, though it was also sometimes remaindered. What happened in the sixties is that Beardsley was wafted back to the center of fashion on the zephyrs — indeed, the Zeffirelli — of the art nouveau revival (this one a genuine revival of something previously obscured and despised). Beardsley’s polymorphous perversity is precisely the “kinkiness” prized on the Swinging London scene. His designs sell today as greeting cards in the slot next to the camp thirties stills of Dietrich and Carole Lombard. Beardsley, highest of high Catholic camp (his drawings were listed by Susan Sontag in 1964 in the canons of camp), has been carried shoulder-high, on the pretty bacchanal route of current camp-followers, into his kingdom, the transvestitely dandified realm of Carnaby Street.

The respectable pundits have now underlined the Beardsley bang with their own boomings. Really, they might have mentioned Beardsley’s greatness a little sooner. More to a serviceable point, the bang has been grounded on firm, square scholarship. The 1966 Beardsley Exhibition in London was an important assembly, underscored by the bibliographical scholarship of Brian Reade’s catalogue, and in 1967, his Beardsley book. The Stanley Weintraub biography of 1967 conscientiously assembles the facts.

Live (love) now: die sooner or later.

Thus the classic burden of lyrical art. Aubrey Beardsley was above all a lyrical artist, but one who was pounded and buckled into an ironist by the pressure of knowing — which he did virtually from the outset — that for him death would be not later but sooner.

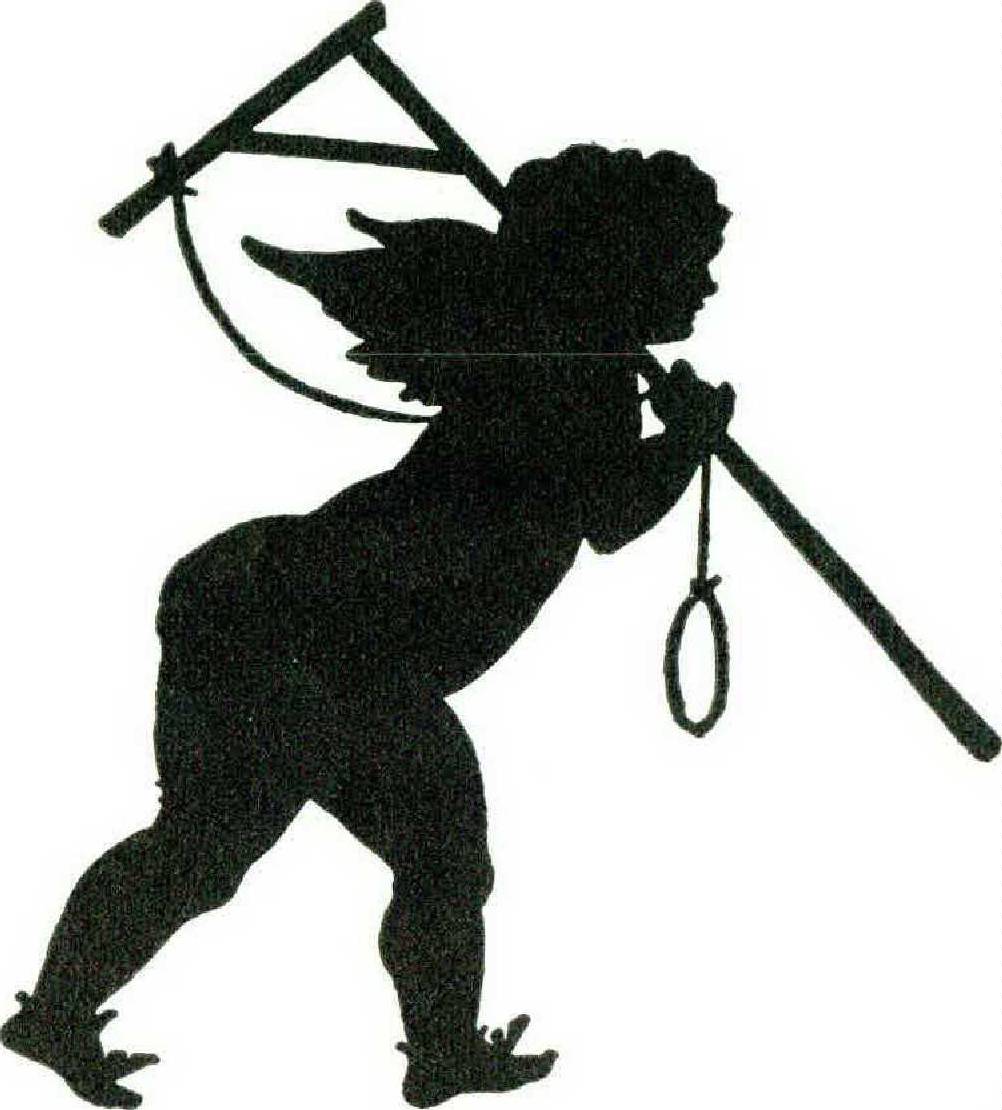

In his terrible haste, he was first an infant prodigy and then a prodigious worker —though in a delicate social gesture that would suit one of his masked pierrots, he disguised his hard work in evening dress and sophistication. He died of consumption in 1898, when he was twenty-five. He must be — as well as, simply, a very great artist — the most intensely and electrically erotic artist in the world. But he is an erotic artist for whom Cupid himself can prefigure death. In one of the decorations Beardsley drew to his own sinister Ballad of a Barber, a sonsy, callipygian, wing-flirting amoretto comes flouncing along in profile silhouette, like a boy tart on the beat. This beat, however, is also a march to the scaffold and a road to Calvary.

Beardsley’s Cupid is shouldering not quiver and arrows but gallows and noose.

Beardsley is lyrical by virtue of his gift of line, which resembles the gift of melodic invention. Sheerly, Beardsley’s lines, like great tunes, go up

and down in beautiful places. True, they often, by the same stroke, represent objects, but never for purposes of reportage or narrative. Not a dot is put in for description’s sake. Beardsley inserts nothing on the grounds that it was or would be there. He attends only to what, by compulsion of the design, should be there.

Illustrator though he was by choice, and sometimes of his own literary fictions, and though he was also (which not all writers are) a consuming reader, he isn’t, as draftsman, in the least “literary.” The tension that dominates all his compositions is entirely in the design and the medium, not borrowed from the incidents, and still less the characters, of any story he may adopt. This makes it less strange than it superficially looks, in a personality so passionately literate, that Beardsley didn’t, after the Hamlet picture of his teens, very much draw on or from Shakespeare. (Dickens, whom Beardsley as a schoolboy accurately diagnosed as a cockney Shakespeare, he stopped quarrying, after he, at the age of eleven, decorated a set of place mats with Dickensian characters.) Shakespeare was too literary for Beardsley’s requirements, the images too perfectly fused into their literary vehicles of character and action. Beardsley could make more of the — so to speak — literature in the music of Wagner.

What Beardsley plunders from literature are matters common to all the arts: pure style, pure image. Pope figures to him as the epitome of the rococo, Ben Jonson of the baroque. (In this sense, Shakespeare has no style.) Out of the given style, he sets his virtuoso line to pluck a pure lyrical image. He is after the geometric essence of relationships, without reference to the personalities between whom they subsist. He is after pure tension: tension summed up by and contained within his always ambivalent images.

Sometimes the image is presented, in its complete irony and ambiguity, through a single piercing contrast — a solo black outline that severs a white area into two spaces; the rich imaginative material is all condensed into a single outline. By the converse process, Beardsley could tease material out from the image and spin it into a decorative setting which, because its metaphors repeat those of the image itself, intensifies the image it enshrines. Beardsley’s conversion to Catholicism, which his recent commentators rightly do not take very seriously as a religious act, was a logical continuation of his work. The contemplation — the cult, the image — is the essence of Beardsley’s art. His elaborate decorative schemes are jeweled monstrances for the display of highly ambivalent hosts or altars enshrining relics of dangerously numinous monstrous saints: never more so than in the two great pictures The Baron’s Prayer, from his Pope sequence, and Volpone Adoring His Treasure, which actually and expressly depict metaphors of their own essence by ironically depicting acts of warped worship at satirized altars.

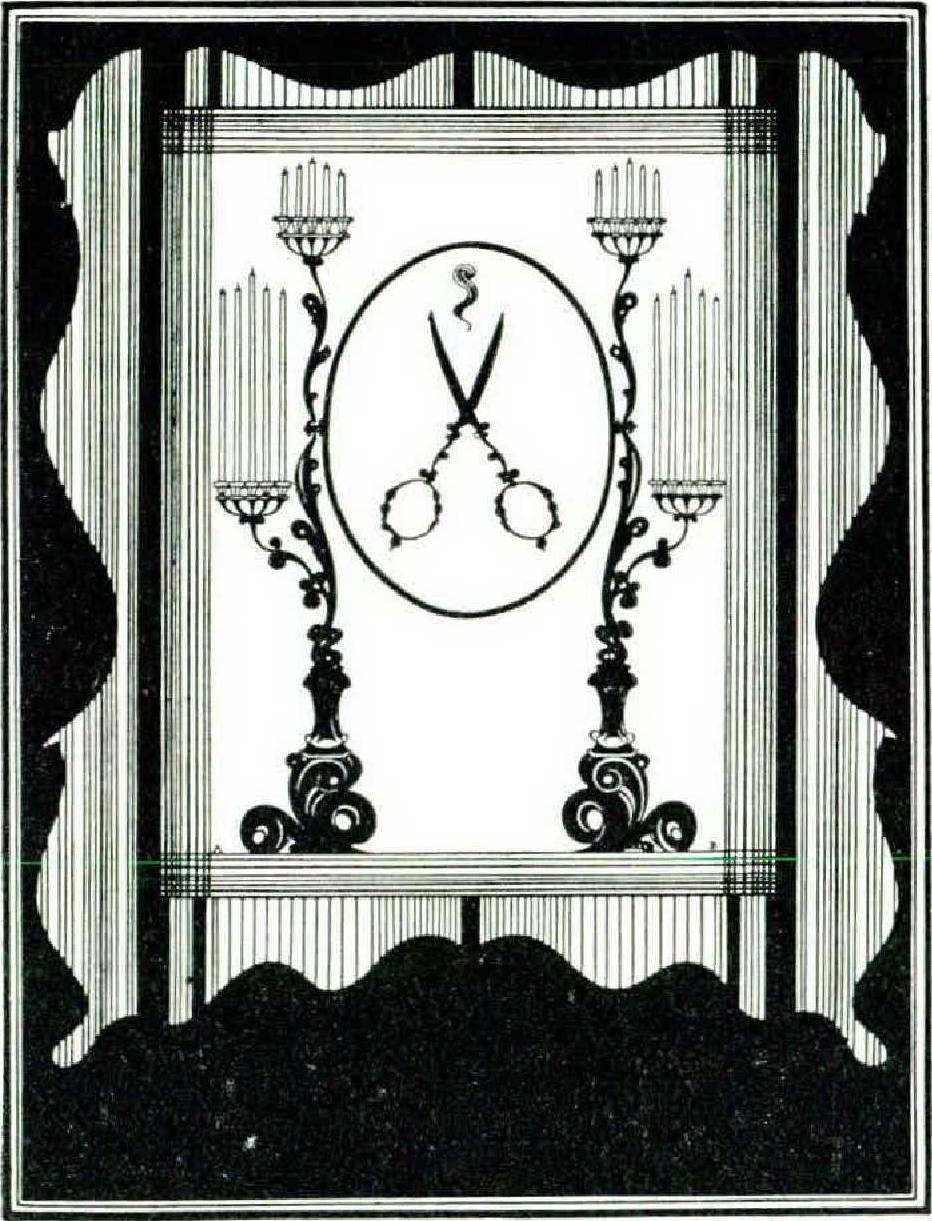

It is again an altar — flattened, diagrammatized, seen in plan — that Beardsley creates, in one of the most lethally ambivalent of all his images, for his front cover to The Rape of the Lock. In an oval that suggests a miniature painting hung on a drawingroom wall and thereby betokens Pope’s miniature and domesticated epic, Beardsley places “the fatal engine,” the scissors, reaching murderously up toward that lock of curly hair which, as Pope quite consciously intended (“Oh hadst thou, cruel! been content to seize/Hairs less in sight, or any hairs but these!”), stands symbolic substitute for pubic hair. At the same time, the oval is the mirror on Belinda’s dressing table. The glass stares directly at the artist, at Beardsley; and what he shows reflected in it is his own castration complex. At this altar, he is the sacrificed victim, doomed to sexual frustration and death. The lock of hair makes allusion to the cutting of a few symbolic hairs from the head of the animal victim in classical sacrifices; and by the disposition of the lock and the scissors Beardsley sketches a distant memory of the skull mask of classical altars and funerary sculpture.

Simultaneously, this stunningly elegant design makes a metaphor of the ambiguity of elegance itself, through the tension it sets up between, on the one hand, the budding, twirling rococo candlesticks, plus their silhouetted echo in the sides of the frame (which consists at once of a pair of further candlesticks and of bulbously buttocked female torsos), and on the other, those inexorable straight, ruled, reduplicated black lines, which visibly act out the shearing and severing deed of the scissors. Beardsley’s elegance is budding, rotund, fruitful — but also disdainful and severe; he is an artist who will soon be compelled to the ultimate act of good taste, that of leaving living to be done by the servants. Inevitably Beardsley’s own regular method of work was by the artificial light from two candlesticks. His worktable was a sacrificial altar. All his designs were images whose very working was an act of desperate invocation.

Destined to cult, he was destined pre-eminently to the Catholic cult of the Madonna. In Beardsley’s life, his mother is as regularly there, and his father as regularly absent or unnoticeable, as the Madonna and Saint Joseph in Christian iconography. His elder sister, Mabel (I wonder if Wilde named Mabel Chiltern for her?), figured to Beardsley as the mother writ one size smaller. Mabel takes several, seldom unerotic, roles in his oeuvre: the Madonna writ, so to speak, as Mary Magdalen. Socially, Beardsley was dependent on his mother and sister to hostess for him. As a child, he probably felt an unusual material dependence on his mother, since, unusual for the period, she worked. And as a dying man, Beardsley returned to the child’s state of bodily dependence on his mother. In Beardsley’s novel, after Venus and Tannhäuser have made love, Venus is literally carried — “in a nice, motherly way” — to bed in the arms of her “manicurist,” Mrs. Marsuple.

In 1896, two years before he died, Beardsley carried the image of the mother-and-child group to its utmost sardonic and high-comedic pitch. In TheAscension of Saint Rose of Lima, the child, though grown-up, is still enfolded within the outline of the protector’s mantle, and is, as in the Barber drawing, female. So, it should be supererogatory to say, is the Madonna. It is by a singular infelicity, of the kind ironic artists seem fated to in their interpreters, that a recent study of Beardsley’s eroticism mistakes the erotic point of the drawing by supposing the saint to be ascending “in the embrace of the heavenly bridegroom.” Not she. As a matter of fact, the Madonna is saving her from an earthly bridegroom. The very pretty, camp, and Firbankian passage in Beardsley’s novel Under the Hill which this drawing illustrates recounts how, on the morning of her wedding day, Saint Rose “perfumed herself and painted her lips, and put on her wedding frock, and decked her hair with roses,” and then, from a hill outside Lima, spent some moments calling tenderly upon “Our Lady’s name.” In answer the Madonna descends, kisses her, and carries her up to heaven.

Even when she is not present and personified, the mother dictates Beardsley’s very point of view. Beardsley was a latter-day Mannerist. The common complaint of his contemporaries against his figures, especially his women, was the complaint made at all periods against all mannered figures, that they are too tall and have necks like giraffes. His lovely, gentle, and unsentimental drawing (once owned by Oscar Wilde) of Mrs. Patrick Campbell was said to make her “nine feet high.” Mannerism: mamaism. The elegance of these elongated persons, who are so an fait in the world, is a memory of adults, and quintessentially the mother, seen in child’s-eye view; the slight melancholy they so exquisitely wear is draped on them by the child’s sense of their high inaccessibility.

Mannerism is in itself a style that murmurs of perversity, its elongations a visual drawl that mimics sexual languor. It shows a child’s-eye view, but the child is precocious. Beardsley, who was a precocious child, remained one — as Oscar Wilde pointed out. It is the characteristic of precocious children that in childhood they are astonishing because they resemble adults, In adulthood, they are often — like Mozart and Beardsley — astonishing because they resemble children. The genius of Beardsley’s eroticism is precisely the quality Freud ascribed to the sexuality of children: polymorphous perversity.

It is only the most obvious manifestation of this quality that Beardsley’s subject matter, by his own choice, encompasses virtually the whole sexual spectrum, from delicate bestiality (Venus in his novel masturbates her pet unicorn, Adolphe, every morning before breakfast) to flagellation, which he depicts in the beautiful Earl Lavender illustration that seems to capture even the slight social embarrassment that must accompany actually getting down to an evening’s whipping.

Beardley’s perversity goes well beyond his signing his work with an emblem said to be (in, presumably, the anthropological sense) a fetish symbolizing sexual intercourse; and his polymorphism goes well beyond his alertness to the fetishist value (in the psychosexual sense) of hair (Beardsley can make intricate coiffures of even pubic hair), of tiny pointed shoes, and of hats. Rather, his imagination seems to be in at the actual infantile origin of fetishism. His vision is permanently that of a child lying in bed watching his mother dress for a dinner party. His fantasy hangs this here, tries the effect of that there: everything is a jewel, and everything is a sexual organ. He is allured, yet afraid to touch: driven back on a cold minuteness of detailed attention, and yet passionately curious, with the emotional and involved curiosity children give to sex. The very fastidiousness of his line demonstrates the importance of touching and the fear that has to be overcome in order to do it.

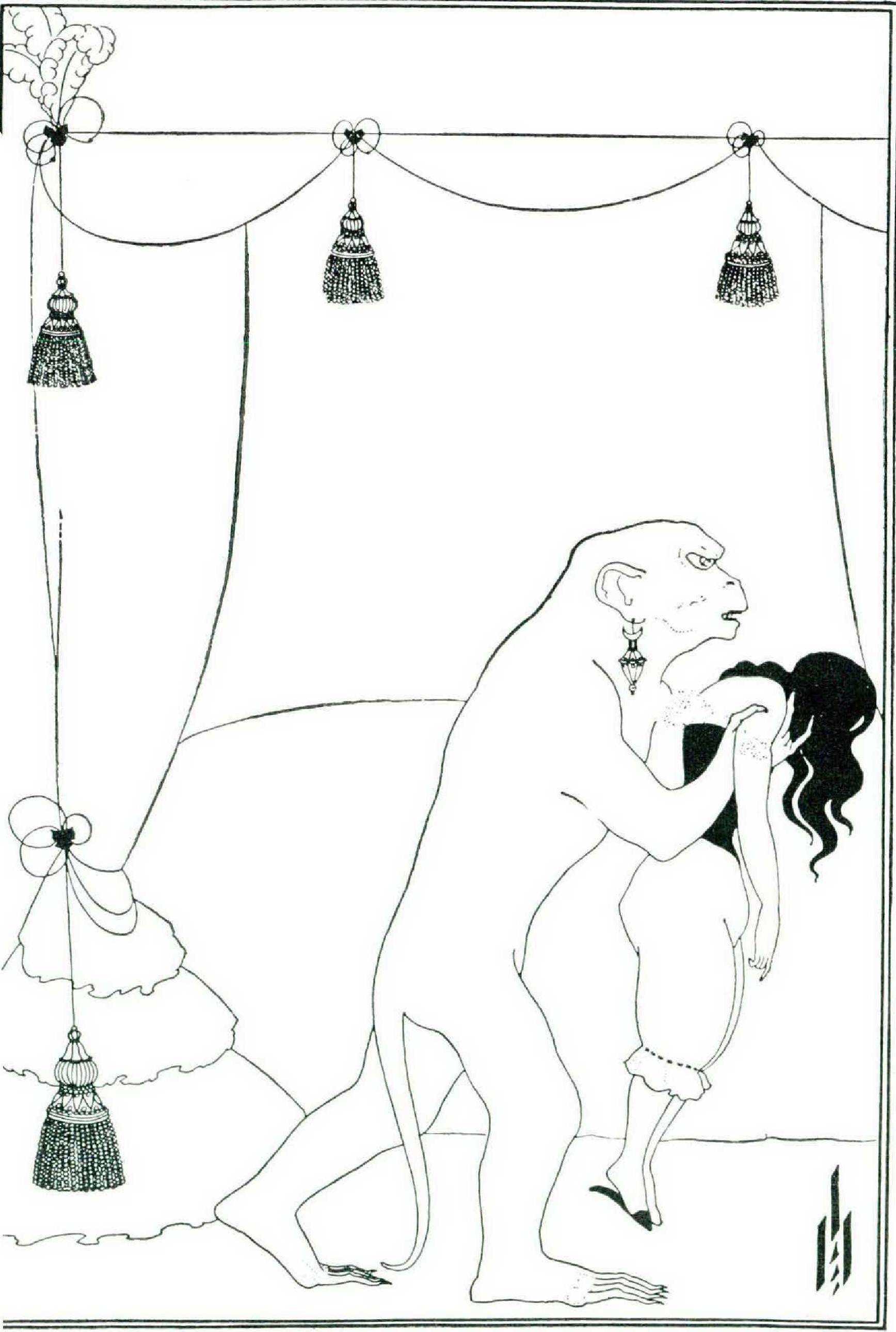

Beardsley’s imagination is forever lying in bed dressing and redressing his mother, and doing it inappropriately. The child’s protest against his inexperience, against the ban on touching, is to glory in his ignorance: he does not know which sexual organs are appropriate to which sex, and he makes deliberate howlers to howl against his exclusion from adult knowledge. They are all breasts and penises, these decorative motifs of Beardsley’s, these drooping swags of fruit and swinging tassels, and he hangs them in places so inappropriate, blatant, or bizarre as to create an effect of perversity — or terror, as he does by that stroke of nightmare genius that makes him a fin de siècle Goya when, illustrating The Murders in the Rue Morgue, he dangles a disdainfully decorative chandelier earring from the lobe of the slaughterous orangutan.

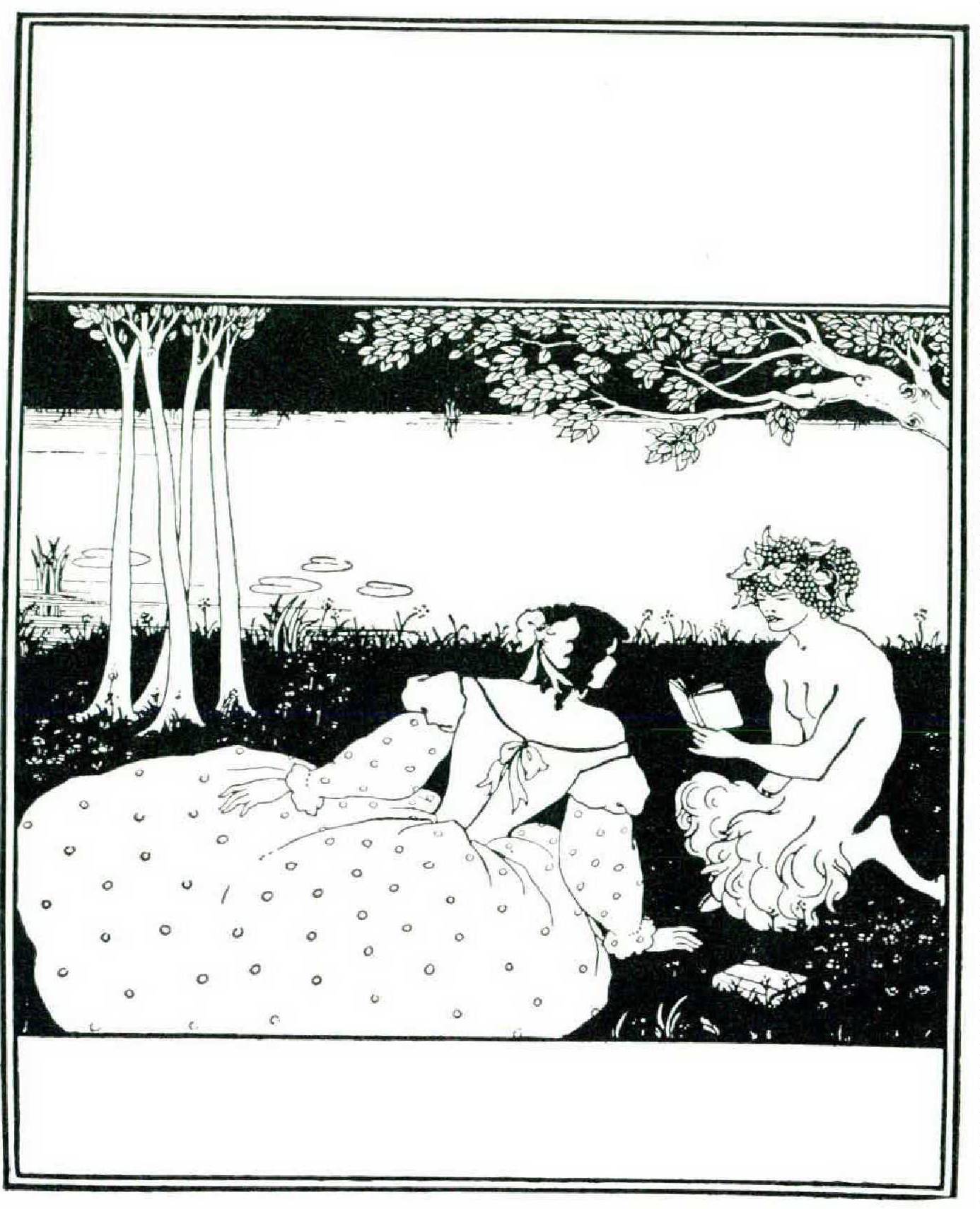

It is his own polymorphism that animates the metamorphism of Beardsley’s images. His decorative forms are ambiguous, caught in the act of changing from one substance into another, his human figures sexually ambiguous. He will depict a hermaphrodite body direct. Or he will clothe the figure, and in doing so, transvest it — investing it, by the same token, with foppish charm. Or he will translate the male-female mixture into a human-animal mixture, as in his favorite motif of the satyr. Even so, the animal portion may be further metamorphosed — into a thing: the clovenhoof feet of one of the “Fruit Bearers” Beardsley drew for his novel are almost the goat feet of rococo and Regency furniture; the creature is a walking console table. For Beardsley, it is not only fountains, chair backs, candle flames that are phallic, it is human figures themselves. One could say of Beardsley’s landscapes what Freud said of “many of the landscapes seen in dreams, especially those that contain bridges or wooded mountains,” namely that they “may be readily recognized as descriptions of the genitals.” The mountain where Beardsley’s Venus keeps state, the hill of Under the Hill, is a pun on the mons Veneris. Effortlessly Beardsley composes in the symbolic idiom of the unconscious.

The polymorphism Beardsley preserved from infancy is not only mirrored directly in what he depicted. It is metaphored in the very eclecticism of his style — an eclecticism so fundamental to his personality that it extends even to an eclecticism among the arts: Beardsley was a musical prodigy, not only performing in semi-public but performing his own compositions, even before he was a precocious draftsman or a writer.

The elasticity which Beardsley needed in order to exploit his temperamental eclecticism he acquired, I suspect, thanks to what looks like a childish method of work. The fastidiousness of his final drawings evidently represents a naive perfectionism; for as a rule it seems to have been built up by an unfastidious process of pencil doodling and pencil sketching, over which, all on the same piece of paper, he imposed his final line by brush or nib.

Only perhaps on such palimpsests, such scratch pads, as he made of his drawings could Beardsley have so briefly accomplished his huge and daring revolution in his own (and presently the world’s) taste. In the six years of his adult life, he evolved from self-imposed Burne-Jonesism and the medieval subject matter imposed by his first major commission (to illustrate Le Morte Darthur) into high rococo and high baroque, virtually inventing a branch of art nouveau as he went.

Beardsley made the revolution deliberately and consciously. At the end of his life he was proposing, as the program for a new magazine, “that it should attack untiringly and unflinchingly the Burne Jones and Morrisian medaeval [sic] business, and set up a wholesome 17th and 18th century standard of what picture making should be.” His own eclecticism and elasticity had not been wanton: he had worked a standard out of them. Perhaps Beardsley was able to pioneer the eighteenth-century revival by virtue of the happy chance of his being brought up in Brighton, that late and fine architectural monument of the eighteenth-century manner. Perhaps the rococo mode Beardsley’s eclecticism finally fixed on was the exotic late-rococo eclecticism of Brighton Pavilion itself, that ultimate Regency extravaganza which is also the first flicker of art nouveau.

Toward the end of his life, Beardsley could barely get through social intercourse without a hemorrhage. Whether or not he had ever been otherwise, the common speculation is surely correct that he was by then exiled from sexual intercourse. The giant erect phalluses of his Lysistrata series ache with sexual frustration. Beardsley, who once alluded to himself as a eunuch and could not have a tooth extracted without self-satirically remarking on the phallic shape of what had been removed from him, illustrates Freud’s dictum that the unconscious apprehends death as castration. The castration-orgasm-death image of Salome kissing the Baptist’s severed head, which is so merely silly in Wilde’s text (Salome is the final proof that Wilde was a great comic writer, since it’s comic unintentionally), is truly horrifying in Beardsley’s drawing. And it is significant that Beardsley chose to illustrate that tableau; it was the publication of that drawing which provoked the commission for the rest of the Salome pictures.

As his disease advanced, Beardsley increasingly transformed his ruling image of the Madonna into Venus, the heroine of his novel. It required the goddess of explicitly sexual love to cast a protective robe around a child increasingly terrified by castration fears. The Madonna’s breasts were too chaste, too limited to the dispensing of spiritual Christian charity, to nourish a child increasingly greedy of life as he was progressively starved of it. At the end of his life, Beardsley solidified his rococo into baroque: first the Second Empire baroque of his Mademoiselle de Maupin illustrations, and then the final, heavy-breasted baroque of his Volpone. Just as he made his rococo pictures emblematic of rococo elegance itself, he builds his great mounds of fruitful baroque ornamentation into a baroque metaphor of greed — at once Volpone’s greed and Beardsley’s greed for life. The drawings are bitter with Beardsley’s sense of the futility of piling up baroque treasure on earth. Treasure, of which Beardsley, who died dunned, had so little, will avail neither him nor Volpone against death. Beardsley could not even be sure, and his contemporaries did not assure him, that by depicting these piles of objects he was building his own monumental tomb and immortality.

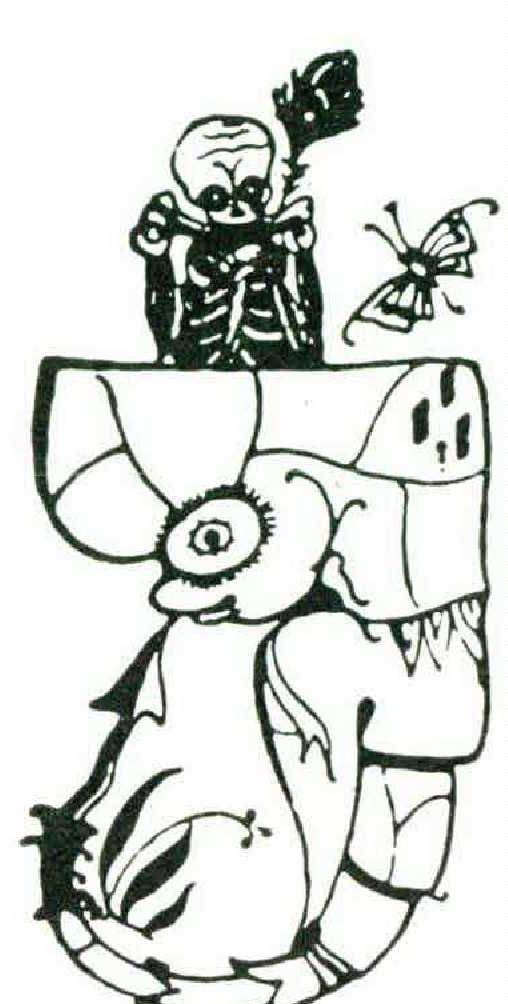

BEARDSLEY’S child’s-eye view is sometimes an embryo’s-eye view. Many of Beardsley’s monsters represent himself. It was his own preconsciousness Beardsley drew in embryonic form, together with his physical unviability. The essence of embryo is the vast head on the feeble, unfit-to-live body of a crustacean snatched from its shell; Beardsley is expressing the consumptive poet’s dread that his body’s unfitness will make him cease to be before his pen has gleaned the teeming brain inside that huge fetal skull. One of Beardsley’s fetal vignettes, as revealing as a doodle, is macabrely explicit. Out of the top of the embryo rises a skeleton. It is Beardsley’s autobiography in shorthand: from the womb to tomb without having truly lived.

Beardsley is still, I sniff out, treated with a grudged admiration, and the cause, I surmise, is still-persisting snobbery about his medium. I have several times called his drawings “pictures,” because that is what they are; and his own reference to “picture making,” in the project for a magazine from which, if only he could stay alive, he obviously didn’t mean to exclude his own work, shows that he knew they were, too. But there is a half-formed idiom (almost as unjust as the colloquialism whereby “artist” means exclusively “visual artist”) which restricts the meaning of “picture” to one done in oils, or at the least, colors of some sort. The tyranny of the easel painting is less stringent now than it was in Beardsley’s lifetime, when it was nimbused in the mystique of the painting smock, top lighting, and the vie de Bohème. But it still exists, and it imposes a snobbery against the medium of print.

It is often forgotten that there were in fact two printing revolutions: one when print was invented, and a second when, in the nineteenth century, it became cheap. Beardsley’s almost exclusive medium was, in one sense, black and white, and in a further sense, print — and cheapish print. His work was intended, was literally designed, to be reproduced, in as many copies as the public would take, in magazines the size and price of not very posh books.

No one could call Beardsley cheap. He is perhaps the only artist of any kind practicing in the nineties who was never sentimental. But the snobbery against his medium wrinkles its nose and dismisses him as superficial or “minor.” I imagine that during the period when Beardsley was signing his A. B. initials in a monogram borrowed from Dürer’s A. D. he was putting himself under the patronage of one of the few Old Masters to have broken through the snobbery barrier and be acknowledged on the strength more of his black-and-white than of his easel pictures.

Beardsley’s adoption of—or at least his virtual limitation to — black and white was an accident of his circumstances, but an accident whose content is cardinal to his artistic development and personality. He did not mean to cut short his observance of the ritual apprenticeship at an art school. He did, occasionally, paint in oils. (And of course, he designed posters as color lithographs.) What cut him off from conventional courses was the sheer lack of time, and presently lack of physical strength, imposed by his disease. And precisely because he lacked time, Beardsley was driven to be modern.

Beardsley, who was admired by ToulouseLautrec, and, incidentally, Yvette Guilbert, expressly upheld the poster — that is, large-scale printed work — as a modern form, arguing against the notion that a picture must be “something told in oil or writ in water to be hung on a room’s wall” and protesting against the “general feeling that the artist who puts his art into the poster is déclassé — on the streets — and consequently of light character.” But he was perhaps not even wholly aware of his own modernity in the matter of print at booksize. Unconsciously he solved the aesthetic crux on which picture making was impaled, in the nineteenth century, by the invention of photography: without having to debate the point, he took pictures away from naturalism and toward decorative composition and image making. By the same effortless stroke he solved the sociological problem. His work acknowledged that for modern people pictures are not things you hang on the walls of your country house and absorb by leisured connoisseurship. They were things you look at reproduced in books. (Despite the pretensions of connoisseurship, the easel painting of the twentieth century, from Fauvism on, takes care to use its non-naturalistic flat colors in ways that will reproduce well.) Having worked all day, you look at the pictures in books by artificial light. The most modern thing of all about Beardsley was that he drew by the same type of light as his drawings would be seen by.

It was his exploitation of the graphic medium that made Beardsley such a far-reaching pioneer. To the influences Beardsley is usually said to have exerted I would add one in, typically, a “modern” medium developed out of the comic cartoon: it was Beardsley’s disposition of white space which inspired the telling placing of Felix the Cat on a mainly white screen. And again: Beardsley, who drew John Bull with a tiny erection under his enormous breeches and redesigned the coinage of the realm by rendering Queen Victoria as a ballet dancer à la Degas, had gone a long way toward inventing the pop art use of jingoistic emblems. In his bitterness, he even invented, on a page of his sketchbook that Mr. Weintraub quotes, the modern typographical joke. Beardsley wrote:

I

AM

TIRE

D.

But black and white gave Beardsley far more than modernity. The violent, unmodified, and unmodulated contrast of the two colors turned his medium itself into a metaphor of the ambivalence in his images and the tension in his designs. Artnouveau is the last, wintry, faintly deviant flowering of rococo, displaying the ultimate tendency of rococo design to fly apart from the center, like a firework or a rose at the very moment of disintegration. And even so. Beardsley’s incredibly tensile design contrives to wire together the sparks or the petals even in the act of flying and falling. Even at the very end of his life, in the front cover for Volpone, he has exerted control over his Hammerklavier, whirligig, almost maddened-by-terror snowstorm of his fears of disintegration. And it is a black snowstorm: the last extension of the rococo stuccowork ceiling, turned funerary.

For black and white was in itself an image, for Beardsley, of the erosion of his life. His medium was, strictly, black on white. (His habit was to leave the white spaces in reserve. Only occasionally did he scratch through his black to the white again or apply chinese white on top.) Black was encroaching on, eating into, the white space. Did he actually think of his lungs, in cockney or the language of offal dealers, as his lights?

And likewise with the culmination of his baroque metaphors of greed. In the initial “M” for the Volpone series, the hungry child is surrounded by breasts and cannot feed. In an initial ”S,”Beardsley confesses that he is destined not to consume but to be consumed. He has drawn the bird of death itself swooping on him, hungry to peck out not his liver but his lights. And in a last drag gesture of defiant inappropriateness, Beardsley draped the creature in one of his flying phallic chandelier tassels and set a dowager’s tiara of orient pearls on its terrifying brow.