Remembering Robert Frank Through the Portraits Others Took of Him

One way to commemorate the late photographer, who pioneered the “snapshot aesthetic,” is to see him the way other artists did.

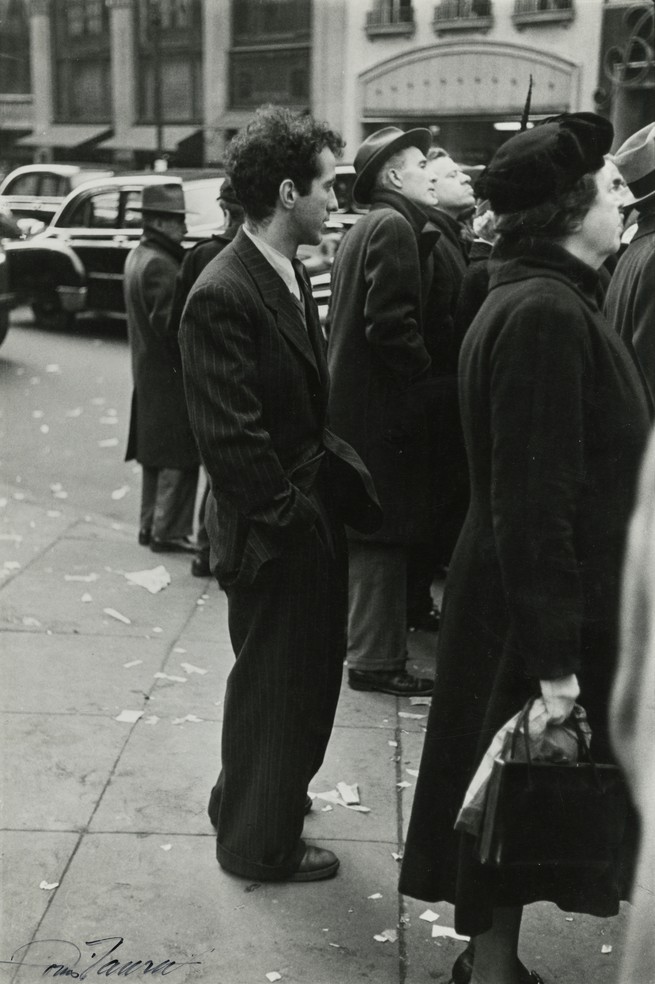

A man stands at the edge of a crowd of onlookers on a paper-littered city street. We cannot see what they are all looking at, but he stands there, also watching. Unlike most of the others in the crowd, he is not wearing a hat, and his pin-striped suit seems oversize for his small frame. While many of the other bystanders raise their head and peer over those in front of them, he looks ever so slightly to the left. Something else has caught his attention.

The man at the center of this 1947 image, by Louis Faurer, is Robert Frank, a photographer who arrived in the United States from Switzerland in March of that year. Upon hearing of Frank’s passing, this photograph—in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery, where I am a curator—immediately came to mind. Faurer’s image compellingly encapsulates what Frank did best of all: observe. As the poet Jack Kerouac went on to write, “To Robert Frank I now give this message: You got eyes.” The photograph adds a profound qualification to Kerouac’s text: Frank’s attention is on something the rest of the crowd does not notice. He looks, but his gaze is not in alignment with everyone else’s.

As the memorials to Frank accumulate, one thing that every writer has noted is that his photographs have become emblematic of how people, to this day, see and depict the world. His photographs were sometimes blurred and seemingly un-centered, like informal snapshots. Indeed, his book The Americans—initially published in France in 1958, then in the United States the following year—did change how humans look at one another, and at spaces. With funding from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, he embarked on a cross-country trip in 1955, with camera equipment in tow. His goal: to photograph everyday life in America through the eyes of someone who had never seen it before. Almost akin to an anthropologist, he sought out scenes that represented, to him, what was uniquely American. He focused on flags billowing in the wind, embracing couples, cowboys, and funerals, to name only a few of the subjects from the 83 images that eventually made it into the publication.

But what was it to look at Robert Frank, rather than be observed by Robert Frank?

As the Faurer photograph shows, in his 20s Frank was a slight man with curly hair. His gaze was intense—or so we infer from the slouch, the hands in the pockets, and the slightly arched neck. He had arrived in New York from Zurich (he had wished, he said, “to get away, further … to America”). Once in New York, he focused his lens on a myriad of things, from people avoiding his gaze with newspapers to the reflections of the city’s buildings in puddles on the street. Although fashion wasn’t his preferred subject, he worked at Harper’s Bazaar and Junior Bazaar. At the latter publication, he met Faurer, who would become a lifelong friend.

Faurer’s candid shot from 1947 is not exactly from the beginning of Frank’s career as a photographer, yet it marks the moment he started his exploration of the United States, the country that would become the source of his most well-known images.

By the early 1960s, Frank claimed that he had abandoned photography, instead moving to film. As he explained in his 1972 book, The Lines of My Hand, “In making films I continue to look around me, but I am no longer the solitary observer turning away after the click of the shutter. Instead, I am trying to recapture what I saw, what I heard and what I feel. What I know!” Aided by the time-based nature of film, he could now reconstitute a scene and play it back, something he couldn’t do with still photography. Observing, nevertheless, continued being his work.

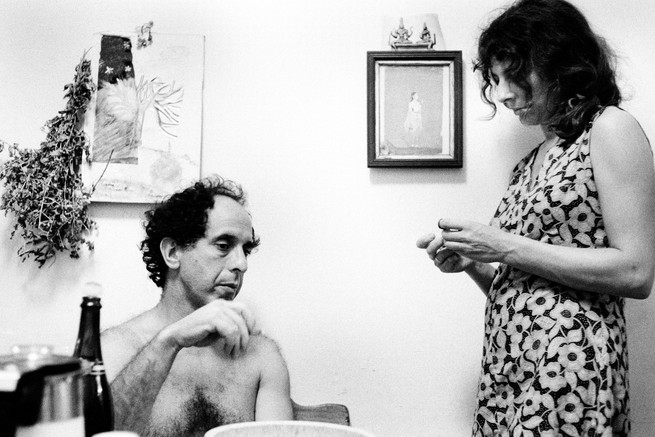

The photographer and filmmaker Danny Lyon was also drawn to Frank and his way of looking. As he set out to become a photographer in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Lyon repeatedly consulted his copy of The Americans, comparing his images with those by Frank. The two eventually met and became friends and collaborators; Lyon, like Frank, would also shift his focus to film. He even lived with Frank and his first wife, the artist Mary Frank, in 1969, at their apartment on 86th Street in New York. There, he photographed the two of them at the dining table; that picture now resides in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery.

Lyon later inscribed the photograph along its edges: He credits his father, Ernst, with teaching him “how to see,” while he says Frank taught him “how to run a moviola” (a film-editing device). Lyon “watched him film, trying to learn how to do it.” Yet Lyon’s image of Frank is not obviously that of a person with a voracious eye. Frank is not out in the world, taking it in, as he appears in the Faurer portrait. He is also not evidently the revered artist and mentor Lyon had admired for so long. Instead, Frank appears at rest, shirtless, possibly in mid-thought, as he sits before a table strewn with the remnants of a meal. It is an intimate and candid portrait, one without much pretense. From Frank, Lyon absorbed not only the ins and outs of film machinery, but also how to make an evocative image that asks viewers to investigate its details further.

Frank’s legacy thus exists not only in his films, his publications, and his thousands of still photographs, but also in the work of those who learned from him and came after him. To this day, photographers including Katy Grannan and Alec Soth have credited Frank as a source of inspiration. He continues to guide viewers to observe with the crowd, veer ever so slightly to one side, and notice the overlooked.