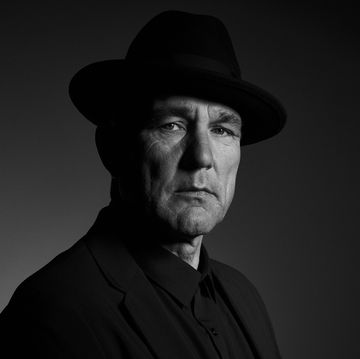

When Russell Brand turned 40, five years ago, he found himself facing a crisis. He felt adrift. He thought, simply enough: "I don’t want to live how I’m living."

Having risen to fame in the UK as a presenter on MTV and E4 in the early 2000s, Brand achieved international celebrity status in 2008, when he played a ramped-up version of himself in the Hollywood romcom Forgetting Sarah Marshall. The next few years were a blur of tabloid and talk-show ubiquity. There was also his brief, high-profile marriage to the pop star Katy Perry. Then, for reasons both voluntary and otherwise, that all went away.

Brand is Zooming from the kitchen of his bucolic Oxfordshire home, where he lives with his wife, Laura, and their two daughters. There are grey streaks in his beard; his hair, still long, stays hidden in his hoodie. When he was in the spotlight, Brand says, “There was an obvious cultural template that I was pursuing.” Today, “sitting back, older, with a family”, he wonders what was the real value of that. His crisis, he says, was spurred by the panic that comes with middle age. “It’s the end of fertility or of virility. It’s the recognition that there is more life behind you than there is in front of you. That sense of ‘Oh my God, I’m not ascending.’”

So, he consulted a few men in his recovery community. (Brand been in recovery from drug and alcohol addiction for 18 years.) One told him, “This is normal. You should feel this now. If you didn’t feel it, it would be worrying.”

Brand realised he needed to come to terms with the death of his fame because it represented an inauthentic version of himself that he’s still, inevitably, drawn to. “It’s a difficult thing to let go of,” he says. “There are some things that I look at [and think], ‘That looks so cool!’ I see myself in the tight clothes, or the crazy hair, or the eye makeup, and I think, ‘That in a way must have been simpler.’ But a lot of those clothes were a bit tight. And I don’t think those high-heeled shoes were good for my lower back.

“You go through little deaths,” he continues. “The little deaths of the phases of your life. And perhaps our progression as individuals is contingent upon if we are able to accept that.”

Now 45, Brand has reinvented himself as an internet thinker. And like just about everyone these days, he’s got a podcast. Under the Skin with Russell Brand is an interview series in which he reaches towards a “transpolitical and spiritual interpretation of life”. It interrogates “whether there are genuine alternative models to how we organise society/reality”, and it considers the “decentralisation of transnational corporations”.

He stops to laugh. Brand’s latest project, Revelation, was released in March exclusively by Audible, a subsidiary of Amazon – the biggest transnational corporation of them all. “I recognise I’m working for Audible,” he concedes. “I don’t know what umbrella that comes under!”

Anyway, he says, Revelation is an exploration of what's most important in our everyday lives. "I’m looking for what is sacred in my relationship with my wife, with my children, with my work. Otherwise, because I’m a drug addict and selfish, I drift toward not caring. Since I’ve become spiritual, I have found that it’s easier to be alive.”

Turning Inward

While writing Revelation, Brand had grand plans to get out in the world: he wanted to hang with Wim Hof, the ice-plunge influencer, or “do an ayahuasca ceremony” (if his recovery would allow that). But then came the pandemic, and in turn, Revelation “became a much more personal examination” of how to live.

But should Russell Brand be telling people how to live? His public behaviour hasn’t always been aspirational. After he split from Perry at the end of 2011, she told Vogue: “Let’s just say I haven’t heard from him since he texted me saying he was divorcing me.” Meanwhile, his open-ended investigation of lofty ideas can seem sincere; yet it can also feel flighty, messy and performative.

Yet part of Brand’s charm is that he seems comfortable with the fact you may never take him seriously. Whether you feel he has the right to pontificate is your call; he’s not going to push you. “The edicts I’m espousing that I would be comfortable with people living by aren’t mine,” he says. “I try to point out that this is a perennial system of belief that has been found everywhere from Iceland to Tibet."

At 40, his crisis year, Brand also had the first of his two children with Laura. “A lot of the clichés have proved true,” he says. “It’s both joyful and exhausting. And when they’re asleep, it’s magic, man.” Parenthood has provided a clear duty and purpose. "I now have no doubt what the most important things are. I would have to make a really deliberate choice now to care about other stuff.”

In 2017, Brand enrolled in a Master’s programme – religion in global politics – at the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies. “I was not as famous as I had been, but pretty famous,” he says. “And I was 20 years older than everybody.” He did his best to hang with the kids and says his presentations were solid – “I was able to bust out some performance skills” – but the written assignments killed him. “I didn’t finish the course."

Brand floats his time at university as the kernel of a film: comedian-turned-YouTube sage goes back to school! He’s accepted the death of his old self. But, it seems, it’s nice for him to idly imagine that big-screen return. “I’m sure there’s something in it,” he says, smiling. “It was like a John Hughes movie. Is there a lane for this? Could this work?”

Brand Values

Feel life's spiralling out of control? Try these tips from a man who knows a bit about recovery and discovery.

Stay in the moment

In moments of internal panic, Brand recommends shifting attention to your breath, looking at the palm of your hand, and telling yourself, "I’m aware that this is my hand and there is life in it."

Don’t go it alone

Brand relies on his recovery community and suggests building one of your own, with friends or colleagues. “I’m not so hubristic to think I can deal with darkness without help,” he says.

Find your core fear

“I was taught this by the 12 Steps: write down the thing that’s happened and how it made you feel. Then you can ask yourself what your fear is. ‘This person was mean to me at work, I’ll lose my job, I’ll be poor.’ Chase it down.”

Pursue gratitude, not happiness

“I stay in touch with gratitude. If people are reading this, they subscribe to Men’s Health and have something to be grateful for. There is great beauty in the world.”