Banksy: The Enigmatic Street Artist

For someone to be internationally acclaimed yet remain largely unknown sounds like the ultimate paradox, but contradiction is the lifeblood of Banksy: street art anti-hero and darling of the salerooms.

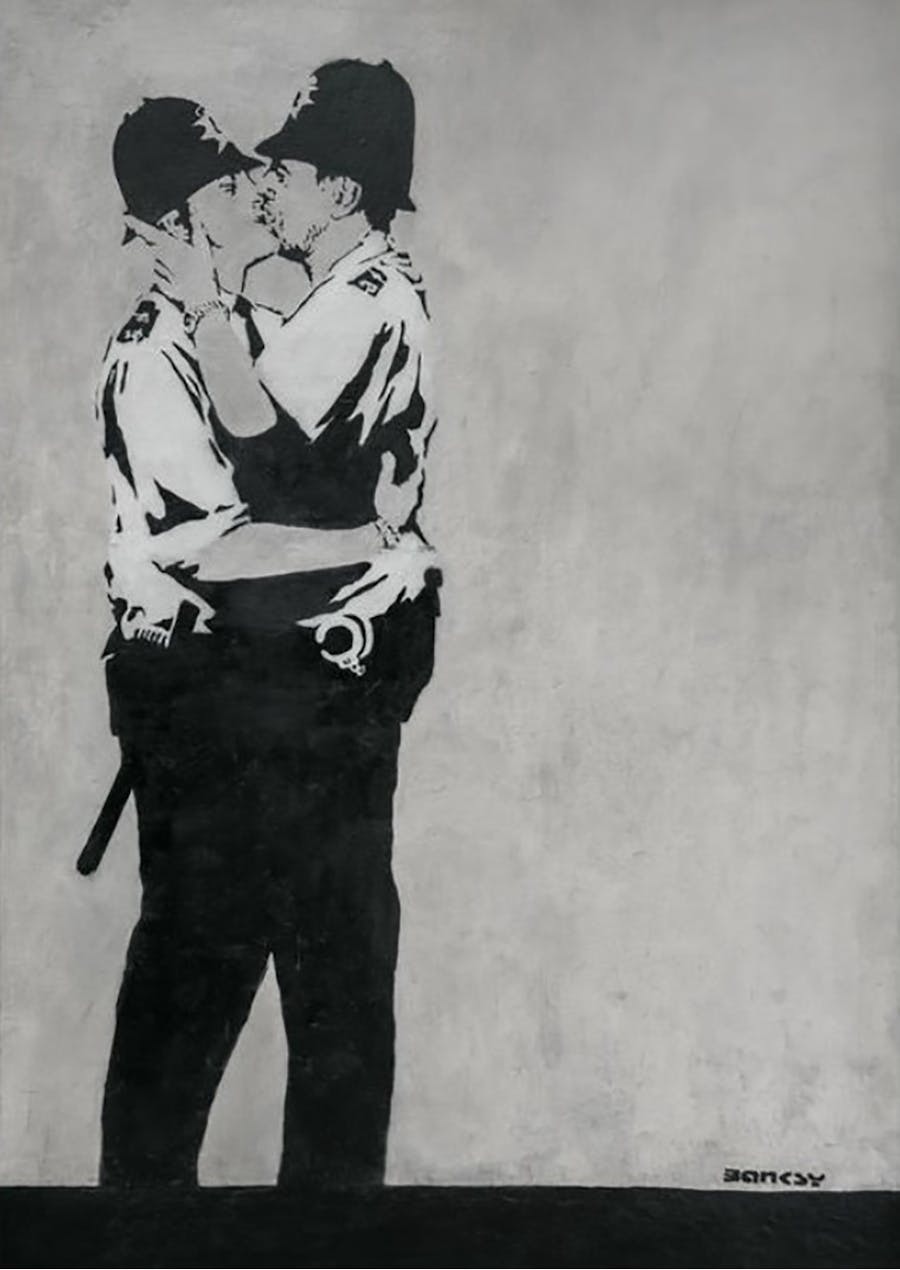

Most major cities have, or have had at some point, a Banksy artwork in their midst. From London to San Francisco, Berlin to Sydney, his provocative graffiti interventions – rat and chimp motifs, kissing policemen, fake banknotes amongst them – have mysteriously appeared on walls and bridges, raising awareness, smiles, and eyebrows.

Like all great satirists, Banksy’s use of humorous imagery and pithy slogans draw attention to serious global and political issues. With capitalism, terrorism, war, and The Establishment often the targets of his derision, it seems no subject is off-limits to his aerosol can.

But how, and where, did it all begin for Banksy? Because much of his life is cloaked in secrecy, including his early years, opinions are divided on his true identity – but one thing upon which most commentators agree is that he was born in Bristol in 1974.

His friend, the graphic designer Tristan Manco, has claimed that Banksy is the son of a photocopier technician and that he trained as a butcher before becoming interested in Bristol’s emerging graffiti subculture in the 1980s.

See also: Street Art: The World’s Best Kept Secret

The transition from freehand spray paint to stencilling was born out of necessity rather than conscious planning. In Banksy’s own book, Wall and Piece (2006), he explained how, as an 18-year-old painting a message on the side of a train, the urgent need to hide from the British Transport Police prompted him to develop his trademark style. “I spent over an hour hidden under a dumper truck with engine oil leaking all over me,” he wrote.

“As I lay there listening to the cops on the tracks I realized I had to cut my painting time in half or give up altogether. I was staring straight up at the stencilled plate on the bottom of a fuel tank when I realized I could just copy that style and make each letter three feet high.”

True to Banksy’s contrary style, however, commentators have since questioned this anecdote, instead suggesting that he was influenced by French graffiti artist Blek Le Rat, who had been stencilling urban creations in Paris since the early 1980s. Banksy has also claimed that he switched to using stencils when he was 21 years old, not 18. Either way, he harnessed the “power” of his new medium, telling Manco: “All graffiti is low-level dissent, but stencils have an extra history. They’ve been used to start revolutions and to stop wars.”

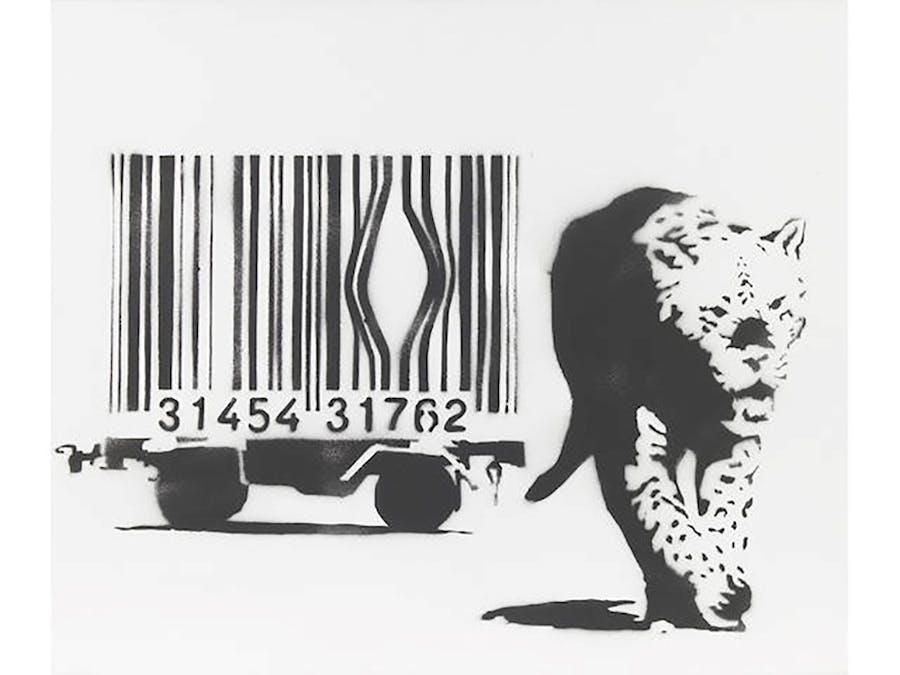

Banksy headed to London at the turn of the century and had his first informal exhibition there in 2001. His first gallery show, Existencillism, in Los Angeles the following year saw the debut of works including Leopard and Bar Code (2002) and Bomb Hugger (2002).

Whether adorning interior or exterior walls, the aims of his art remained constant: to hold up a mirror to society and to question the status quo. In Wall and Piece, he unleashed a bruising attack on what he terms the ‘Brandalism’ culture of corporate advertising in social spaces.

See also: In Conversation with Graphic Artist Shepard Fairey

“Any advert in public space that gives you no choice whether you see it or not is yours,” he wrote.

“It’s yours to take, rearrange and reuse. You can do whatever you like with it."

“Asking for permission is like asking to keep a rock someone just threw at your head.”

In addition to nocturnal activities on city streets, a heavily disguised Banksy began hanging his own artworks, complete with wall labels, inside high-profile galleries and museums. Part of the challenge for him was to see how long each of his works remained in place before being removed by museum staff.

A small oil painting entitled Crimewatch UK Has Ruined The Countryside For All Of Us (2003), described on the caption as “a beautiful example of the neo post-idiotic style”, lasted just two and a half hours on the wall at Tate Britain in 2003, while the Warhol-esque Discount Soup Can survived six days in the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York in 2005.

These brief and daring stunts put Banksy’s notoriety – and desirability – on an even steeper trajectory. Soon after the Tate Britain escapade, a gallery put up a second version of Crimewatch UK £15,000. Fast-forward three years from the MoMA intervention, and an adaptation of his tinned soup oil on canvas, Tesco Value Tomato Soup, sold at auction in 2008 for $175,420.

By this point, Banksy’s work had caught the eye of the rich and famous. American singer Christina Aguilera paid £25,000 for three of his artworks during a visit to London in 2006. A ‘Banksy’ was now the must-have home accessory of celebrities including Angelina Jolie, Jake Gyllenhaal, Serena Williams and Jude Law.

The following year, he was named Greatest Living Briton in the art category of a British TV awards program (overall winner was The Queen). ‘Street art is now mainstream’, declared The Guardian in 2008.

Banksy was easily the most famous artist that nobody had ever seen. When he was listed as one of Time Magazine’s 100 most influential people in 2010, alongside Bill Gates, Oprah Winfrey and Barack Obama, he sent the magazine a picture of himself: his head covered with a paper bag bearing a cartoon face. The same year, his documentary Exit Through the Gift Shop was nominated for an Oscar.

Banksy noted wryly: “Nobody ever listened to me until they didn’t know who I was.”

The dichotomy of being a dissenting outsider while producing of some of the most marketable art in the world was not lost on Banksy and didn’t always sit comfortably with him. He is quoted as having said: “Commercial success is a mark of failure for a graffiti artist. We’re not supposed to be embraced in that way.”

It is understandable, therefore, that the more famous Banksy has become, the more he has embraced a reclusive lifestyle. For graffiti artists, anonymity is vital; they work furtively, trying to keep under the police radar. On the other hand, Banksy’s mystery man status only serves to boost his allure – and, in turn, the value of his work. His street art, once certain to be painted over by the authorities, is now being protected by Perspex sheeting in many locations, with some murals even being cut out of walls to be sold to collectors.

Alex Branczik, Sotheby’s head of contemporary art (Europe), explains: “The conundrums behind Banksy, and the paradox of being an ‘outsider’ while becoming an art world insider, simply adds to his appeal.

“The structures of the art world are so inextricable from artists themselves, and we’ve seen this archetype play out before with artists such as Marcel Duchamp, who placed a urinal on display as a critique of museums’ high-mindedness, and inadvertently pioneered the movement of the readymade.”

See also: Keith Haring: The Artist Who's Everywhere

However, it is not just the contradictory nature of the artist that keeps people engaged, but the way he keeps them guessing as to his next move, adds Branczik.

“He has become a key commentator of our generation who creates surprise.

“He can reduce complex subjects and debate into a simple, legible message, often with humour and global appeal, which attracts audiences and collectors across the globe.”

Banksy’s antics show no sign of ending any time soon. In 2013, in a swipe at escalating art prices, he arranged for some of his prints to go on sale for $60 at a stall in New York’s Central Park. Each piece is now worth $20,000 at auction.

And just in case anyone feared that he was mellowing towards mainstream acceptance, his most outrageous deed set minds at ease, and sent shockwaves around the art world.

At a contemporary art sale at Sotheby’s London in 2018, a canvas version of Banksy’s instantly recognizable mural, Girl with Balloon (2006) went under the hammer – and through the shredder. A device had been concealed in the frame, aimed at destroying the work as soon as it was sold to the highest bidder. It fetched £1.04 million ($1.3 million). According to a video filmed by Banksy and released after the event, a glitch in the mechanism meant that only half of the canvas was shredded, but the action had the desired effect nonetheless.

Branczik, who was famously quoted at the time as saying: “We’ve been Banksy-ed”, recalls the moment the painting began to self-destruct. “It was a brilliant Banksy moment! His surprise intervention saw art history in the making in front of the eyes of a packed saleroom.

“We hadn’t ever experienced a situation like this in the past, where a painting spontaneously shredded upon achieving a record for the artist at the time – the whole room was pretty speechless!”

Ironically, but not surprisingly, the damaged piece – renamed Love is in the Bin (2018) – now has an estimated value of up to $2.7 million, almost double that of the original.

See also: Top 10 Stolen Masterpieces

In October 2019, after a frenetic 13-minute bidding war at Sotheby’s, the oil painting Devolved Parliament (2019), depicting the House of Commons full of chimpanzees, was sold for a record £9.9 million ($12.2 million)

And in 2020, while global markets, including the art market, have been battered by the coronavirus pandemic, Banksy’s popularity has remained buoyant. An online auction of his work, hosted by Sotheby’s in March 2020, raised $1.3 million with the bulk of lots comfortably exceeding pre-sale estimates.

A pink version of the print Girl with Balloon alone fetched $463,000.

Interestingly, almost half the internet buyers (47%) were new to Sotheby’s, with 30% of bidders aged below 40 years old – figures that suggest digital sales platforms could play an increasingly vital role in the future of art collecting.

These figures also serve to prove that, even in times of unprecedented volatility, the magnetic, paradoxical world of Banksy keeps on turning.

Search more Banksy with Barnebys

Article by Kay Carson