VHS Revival explores a treasure trove of 80s nostalgia

It’s the winter of 1984 and Richard Donner is embarking on a different kind of project. After shooting to fame with supernatural horror The Omen, a filmmaker renown for his genre diversity would quickly land the original Superman movie, proving himself on the grandest scale before forging one of the industry’s most successful action movie sagas in the Lethal Weapon series. But before tangling with the likes of Hollywood heartthrob Mel Gibson, Donner would try his hand at a Spielbergian adventure featuring a cast of tearaways who’d prove something of an eye-opener. “It is the most difficult thing I could have gotten into,” he would joke during a behind the scenes featurette. “I never anticipated what it was gonna be like. Because individually they’re wonderful, they’re nuts; they’re the warmest, craziest little things that have come into my life, but in a composite form you get them all together and it’s mind-blowing.”

Perhaps an apt description for the sticky metamorphosis of the mogwai, but Donner was of course referring to the juvenile stars of spirited 80s adventure The Goonies, yet another in a long line of Spielberg-produced movies to light up the decade. Using a largely adolescent cast was quite the challenge for the already veteran Donner, but it was a youthful exuberance that translated to the screen, an energy that forged one of the most magical cinematic experiences of the era. It didn’t hurt having Spielberg, who shot at least one of the scenes in The Goonies, as executive producer. Most executive producers are simply there to secure funding, maintain budget and schedule and manage the production’s cast and crew. In fact, some have proven more of a hindrance than anything, even stunting a film’s creativity for those very reasons.

Not Spielberg, a man who turned his ‘kids in peril’ formula into mountains of gold during the 1980s, accumulating the kind of riches that would make one-eyed Willy’s eye water, and The Goonies was no exception, managing a cool $124,000,000 on a budget of only $19,000,000. Spielberg’s sense of bright-eyed adventure is all over this movie, the innovative filmmaker devising the story and even adding elements from his own childhood, like Chunk’s confession of having puked off a balcony, a real-life prank pulled by Spielberg as a kid growing up in Phoenix, Arizona. The film is also loaded with Spielberg and Donner ‘Easter eggs’, references to some of the era’s most lauded adventure movies only adding to the film’s sense of fun and familiarity. There’s the fist-pumping moment when unlikely hero, Sloth, tears open his shirt to reveal a Superman emblem along with the playful innocence hidden beneath his monstrous exterior. There are also visual or audio references to Raiders of the Lost Ark, ET: The Extra-Terrestrial, Back to the Future, James Bond (a series which Spielberg and Donner are both huge fans of), and, perhaps most famously, Gremlins.

The absolutely priceless scene that sees Chunk receive a crash course in ‘The Boy Who Cried’ Wolf’, thanks to a story about “little creatures that multiply when you throw water on them”, isn’t the film’s only connection with Gremlins ― yet another 80s classic that Spielberg was directly involved with. Thanks to a relationship forged on the set of Joe Dante’s controversial Christmas cracker, Gremlins screenwriter and future Home Alone director Chris Columbus was once again recruited to help transform Spielberg’s pirates and treasure concept into narrative gold. Columbus was returning the favour after Spielberg had altered initial drafts of his deeply antithetical Gremlins script, transforming it from an ‘R-rated horror movie’ into something more commercially viable.

Goonies never say die!

Mikey

Because of the Spielberg/Columbus connection, The Goonies isn’t afraid to tread dark territory either, often dabbling in the macabre in the wake of the PG-13 rating, something Spielberg had a hand in establishing. Even after several drafts designed to tone down its horror elements, Gremlins was still considered too raw for a broader audience, as was Spielberg’s Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom released a month prior. A public backlash ensued, but Spielberg had a lot of clout back then, and there was a lot of money at stake if those movies were to be hindered with a 15 rating as proposed, basically eliminating their core demographic. Those in charge yielded to the pressure, but it was bound to happen sooner or later, with or without Spielberg. Society had evolved and 80s kids were much more desensitised, a post-70s sense of irony modifying traditional moral values as cinema ditched the nuclear family for modern-day dysfunction.

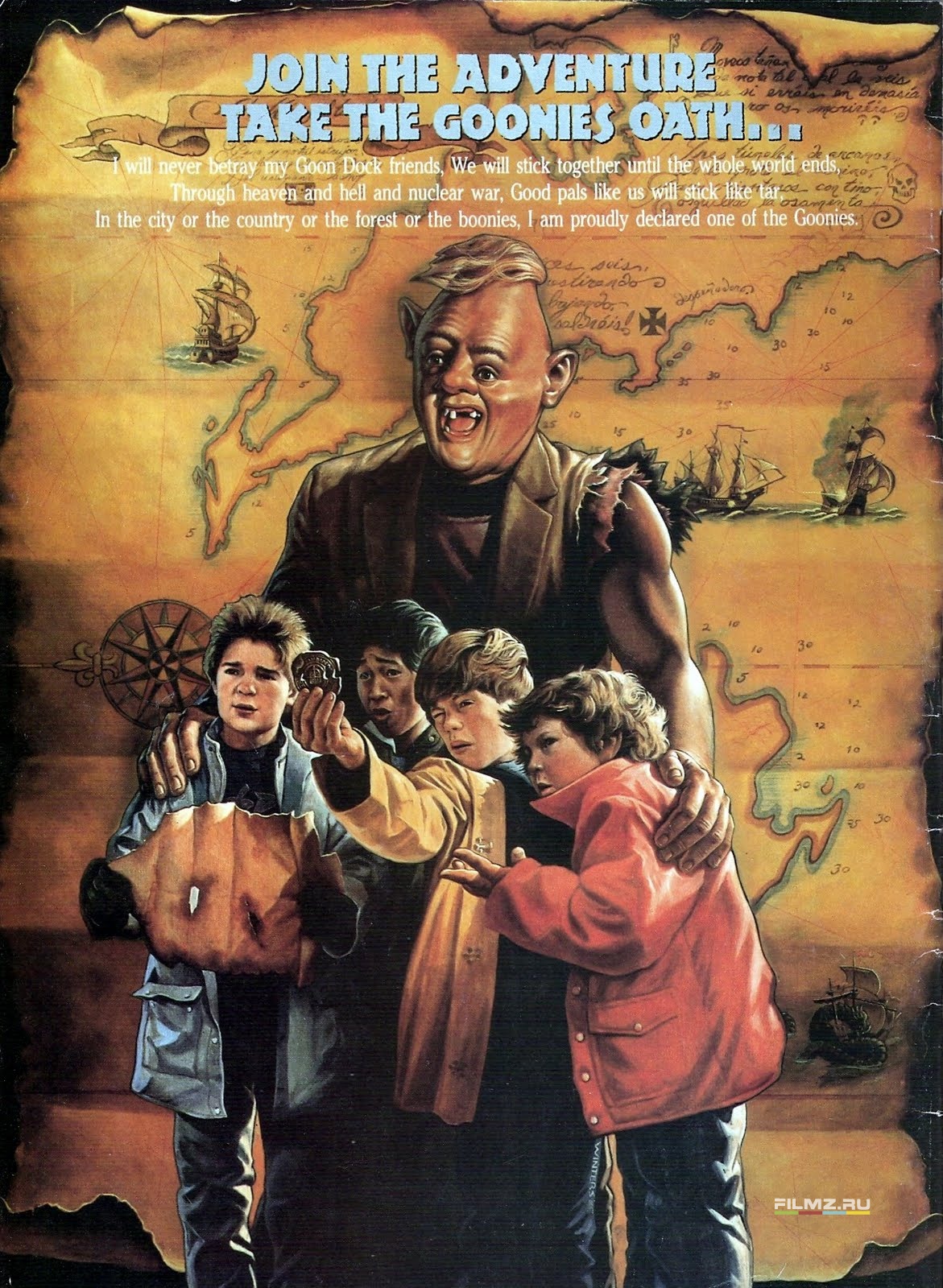

The Goonies centres on the struggles of a dysfunctional community who risk losing their homes to a ruthless property developer as the unwholesome stench of privatisation pollutes their carefree existence. Of all the pirates and gremlins and fictional monsters of the world, nothing is scarier to a child than the very real threat of having to uproot and lose the only allies they have ever known. For kids like the Goonies, named after the Goon Docks area of Astoria, Oregon, the seaside town where the film is set, provincial life encompasses their entire world, a bastion of juvenile comfort that must be defended at all costs. After stumbling onto a pirate’s treasure map and the legend of ruthless pirate ‘One-eyed’ Willy’s fabled riches, our gang set off on a daring adventure that may be their only hope for salvation, their very innocence at stake.

It’s a fairly dark premise, but the movie treads such a fine line that some of its most iconic moments probably wouldn’t exist in today’s sensitive climate, a time when even voice over artists are stepping down due to gender and race issues. There’s Data’s Chinese stereotype for one thing, which though utterly harmless would surely inspire outrage viewed through today’s socio-political lens. Chunk’s iconic truffle shuffle, once the talk of every playground in the Western world, crosses bullying boundaries that are no longer tolerated. Even the visually disfigured Sloth would come under fire for its insensitive portrayal in a 21st century climate. In fact, it’s hard to imagine a movie like The Goonies existing at all.

There are also moments of horror that might struggle to creep past the censors in a movie aimed at such an impressionable demographic. The Goonies begins with a fake hanging and even throws a dead body into the mix. The scene that sees Chunk trapped in a freezer with a frozen corpse brings out the best in the young actor, but stiffs are rarely filmed with such gratuitousness in kids films. Even more jarring is the movie’s often lurid sexual references. The statue erection gag may be pushing it, but a scene in which Mouth wrongly translates to an unknowing Mexican maid, informing her of Mr. Walsh’s secret stash of heroin and the ‘sexual torture devices’ he sometimes uses on unsuspecting guests, is above and beyond. In all honesty, the dialogue is a damn sight funnier than anything that comes off today’s industry conveyor belt. Perhaps we’ve all become just a little joyless.

For a generation, The Goonies is still one of the most joyful experiences that cinema has to offer, a treasure trove of nostalgia that only seems to increase in value. It’s one of those rare, special movies that captures exactly what it is to be a child — the wonderment, the sense of fun and adventure, the notion that anything, however difficult or unlikely or steeped in the fantastical, is possible if you put your heart and soul into it. There’s nothing purer or more magical than the enthusiasm of an unaffected mind. It may be hard to keep a lid on that level of exuberance behind the scenes, but it’s more about managing the temperature, about knowing when and when not to contain, and in Donner and Spielberg the film’s circus of stars were in expert hands. The difficulties Donner spoke of when handling his young cast are actually key to the movie’s power.

The Goonies features one of the most memorable and endearing casts of the era. Some, like Corey Feldman, once again threatening to steal the show as loquacious smart ass, Mouth, would become 80s mainstays. Others, like future Lord of the Rings favourite Sean Astin (Mikey) and Coen brothers collaborator Josh Brolin (Brand), would enjoy greater success later in life. The rest would fade from the Hollywood spotlight altogether. Even flavour-of-the-month, Asian-American actor, Jonathan Ke Quan, already immortalised as Indy’s plucky young sidekick in The Temple of Doom, fell into cinematic obscurity soon after, but how many actors can lay claim to working with George Lucas, Steven Spielberg and Richard Donner in the space of a year? Even for seasoned veterans with countless films under their belt, it’s the stuff of fantasy.

As a unit, there’s no denying our colourful gang’s place in movie history. The film’s juvenile rabble, each referred to almost entirely by their nicknames, are like an 80s toy range come to life, each with their own unique gimmicks and personalities, but there’s a crucial difference. Mikey and co aren’t indestructible superheroes faced with exaggerated dilemmas. They’re a bunch of everyday kids who watching youngsters can easily identify with, who set out to defeat the mundane realities of adulthood with pure, uninhibited enthusiasm and the steadfast belief that good will conquer all. As a kid, it’s easy to imagine you and your friends in the exact same situation, stumbling upon a hidden adventure in some unexplored cave on the outskirts of everyday suburbia, a place beyond an adult’s capacity for imagination. Everyone had their favourite: the courageous Mikey, perennial windbag, Chunk, the mischievous Mouth or Data’s mini Inspector Gadget. For older kids, there was the gang’s peripheral members to relate to, those on the verge of outgrowing their inner child who are drawn into one last adventure, crossing that tenuous bridge between adolescence and adult responsibility.

In 2017, The Goonies was added to the National Film Registry for being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant”. Perhaps even more impressive, on the film’s 25th anniversary in 2010, the mayor of Astoria declared June 7th ‘Goonies Day’, but the film’s influence reaches much further. Following its release in the spring of ’85, The Goonies became an instant classic, later becoming one of the most nostalgic and influential movies of the decade. Even now the film’s sense of adventure can be found pumping through the veins of 21st century Hollywood, most notably in the likes of Stranger Things and Andy Muschietti’s IT! remake, productions that have sparked the current retro revolution and a fondness for all things 80s. Nostalgia is cyclical, each period represented by certain cultural events. The Goonies may not be front-and-centre in that regard, but it peddles on the periphery like a gaggle of rambunctious adolescents off in search of lost treasure. That sense of enchantment, of awe and discovery, it saturates proceedings like a shifting climate, Dave Grusin’s score an evocative haze of intrigue and wonderment.

THATS WHAT I SAID! BOOBY TRAPS! God. These Guys!

Data

Part of the movie’s immediate success was due to the production’s savvy marketing, commercial ties with the red-hot World Wrestling Federation and pop star Cyndi Lauper allowing producers to exploit the MTV pop culture Juggernaut as the peculiar allure of Wrestlemania swept the country. At a time when pop music and movies were becoming inseparable, hit single Goonies R Good Enough provided the film with priceless commercial air time, an element that only bolsters the film’s sense of nostalgia. But The Goonies has passed the test of time beyond simple sentimentality. It may seem a little mawkish in retrospect, particularly through Mikey’s almost ceaseless monologuing, but for kids of all generations it is pure wish-fulfilment, a spirited, well-meaning tale that plays the emotions like a violinist drunk on enchantment. The movie unfolds like a cinematic Hardy Boys adventure spruced with a generous dash of 80s attitude. It juxtaposes pirates and skulduggery with a generation without purpose, though purpose our heroes will surely find.

Despite harbouring late 20th century sensibilities, the film’s moral aspirations more than counterbalance Columbus’ tendency towards the dark side. Take the film’s unlikely hero, Sloth, a character built as a monster who proves beyond any shadow of a doubt that beauty is only skin deep. When Chunk, having been separated from the gang following a run-in with The Fratellis, echoes the fear in every watching child after discovering actor and former pro footballer John Matuszak’s disfigured beast, you run for the hills, but an unlikely bond forms between two characters who actually have much in common. It quickly becomes clear that monsters, like people, are not always as they seem.

The preposterous notion that Sloth will escape years of dungeon solitude to live happily ever after with Chunk and his family is a little icky in hindsight. What will Sloth do when Chunk hits puberty and starts to notice girls? He doesn’t exactly have the kind of face you’d entertain guests with, and God help the poor girl who lays eyes on his favourite Babe Ruth candy bar (I’m sure Chunk’s parents would be more than accommodating). But kids are a quixotic breed given the right motivations, and in Sloth, Chunk discovers another misunderstood outsider, a surrogate ‘Goonie’ just waiting to break free and fulfil his wilting potential. The two are physical outcasts brought together by a common understanding. For younger audiences caught in the sweet bubble of idealism, it’s all very touching.

There may be bigger stars in The Goonies, but Chunk and Sloth’s relationship is the emotional heartbeat, Chunk arguably the most memorable Goonie of all. Actor Jeff Cohen, who was immediately relegated to TV work before falling off the radar entirely by 1991, is the comedic lifeblood of this movie, giving one of the most precocious performances of an era that’s positively teeming with them. Data’s Bond-esque gadgets were also a huge draw, but for pure belly laughs this is Cohen’s movie. His projection of sheer, unmanageable terror in the face of stuntman Ted Grossman’s teetering corpse is one of those gallows humour moments we greedily anticipate with every watch. Then there’s the confession scene with the Fratellis, one so side-splitting you can actually hear Richard Donner chuckling offscreen when Robert Davi’s Jake confiscates Chunk’s ice cream and reduces him to a blubbering mess. I just love those moments, usually reserved for outtakes, when cast and crew members simply can’t contain themselves. It’s nice to know they’re having as much fun as we are.

Another reason why Chunk proves the star attraction is the amount of screen time he spends with the Fratellis. Every great adventure needs a top class villain, and The Goonies gives us three of them. Fratelli matriarch, Mama, is played by one of the most recognisable baddies of the decade in Anne Ramsey, her haggard appearance and curmudgeon aura enough to send any impressionable minor lurching for the safety of their parent’s arms. Based on no-nonsense hillbilly Ma Kettle from the popular Universal Studios-produced films of the late 1940s/early 1950s, Mama Fratelli maintains enough of a comic edge to keep affairs lighthearted, but for kids used to a caring, maternal figure she is a complete horror show, a mean-spirited dog-woman who proves more pirate than One-eyed Willy. Few actors possess the sheer physical presence of Ramsey, and she absolutely revels in the role of remorseless ogre. I fail to think of another actress who could have fit the bill quite so exquisitely.

More great casting comes in the form of the Fratelli brothers. Robert Davi, an actor who made a career out of playing visually striking bad guys, may be most famous for his equally brilliant turn as General Manuel Noriega derivative Franz Sanchez in Timothy Dalton’s final Bond outing Licence to Kill, but for many he will always be Jake Fratelli. The moment when his pockmarked face appears like a flash of hell in a crudely-lit wing mirror, a devilish falsetto ringing in our ears, is truly unnerving. Davi, a professionally trained opera singer who teases imprisoned third brother Sloth with strains of Giacomo Puccini’s opera “Madama Butterfly” (the actor’s suggestion) certainly had his work cut out. It’s no mean feat forging a villain who makes a physical monstrosity like Sloth, an eyesore typically synonymous with the horror genre, seem almost immediately sympathetic. Thanks to our terrible trio, it doesn’t take long to figure out who the true monsters are, and they’re not daubed in 5 hours’ worth of practical effects grotesquery.

Just as memorable is Francis Fratelli (Joe Pantoliano). One of the most talented supporting actors of his generation, Pantoliano has a particular talent for sneaky villains with a darkly comic edge, and he provides the perfect foil for his jealous sibling. The two are absolutely pathetic in their attempts to please Mama, and Pantoliano, with his shady tone and ceaseless sense of injustice, is the kind of snivelling toad who’s just begging to be stepped on. Ultimately, it’s this jealous dynamic that turns a crew of ominous crooks into a foolish rabble kids can just as easily laugh at. They may be cruel and intimidating, but they’re also bumbling and without focus, consumed by the kind of inner bickering that negates their fearsome reputation and empowers their juvenile prey, and in the Goonies they more than meet their match. Their immediate chemistry in a joint audition landed Davi and Pantoliano the roles of the Fratelli brothers. Together they’re pure magic.

The 80s gave us an abundance of kids adventure movies, but The Goonies has such a broad appeal, and there’s such a genuine quality to it all, as if the actors involved are embarking on a journey beyond the realms of fantasy. In order to make the experience as real as possible and elicit the necessary reactions, Donner and Spielberg pulled all kinds of tricks that blurred the lines between fiction and reality. Crucially, the film was shot almost entirely in sequence over a period of five months, allowing the cast a very real sense of adventure, the kind that’s impossible to achieve through a series of non-linear shoots. Most famously, Donner kept the movie’s spectacular pirate ship set a secret until his juvenile cast actually splashed down and saw it with their very own eyes. Though part of the scene had to be re-shot to cover-up Brolin’s genuine “Holy Shit!” reaction, what we witness onscreen are their natural reactions. We experience the moment as they do.

Yeah, but you know what? This one, this one right here. This was my dream, my wish. And it didn’t come true. So I’m taking it back. I’m taking them all back.

Mouth

For all the mystique of One-eyed Willy, for all the booby trap adventures and mouth-watering treasures, it’s the bonds that our kids form, those rare instances of unaffected friendship, that prove most precious, the promise of shared experience that truly resonates. Naturally, there’s also the bittersweet dawning of puberty to contend with, those scenes in which Mikey steals a kiss from his brother’s squeeze, Andy (an adorable Kerri Green), and the blossoming attraction between Mouth and Martha Plimpton’s sarcastic-teen-with-a-soft-centre, Stef, particularly telling. There are few things as magical or as universal as the first stirrings of a libido, urges that ultimately strengthen the group’s bond, emboldening their leader and allowing the Goonies the determination to overcome odds beyond the powers of helpless children.

Throughout their adventure, the gang are hugely conflicted, torn between the ingrained pessimism of adulthood and the youthful belief that it’s not too late to save the day, between quitting and turning back or seeing through on their promise. They’re trapped between responsibility and irresponsibility because they’re unsure of which is which. Is it responsible to give in and avoid the potential perils that lay ahead, or is it irresponsible to abandon all hope and return with their tail between their legs, grown-ups in the eyes of their parents, but failures in the deepest understanding of their souls?

Before Rosalita’s liberating discovery and the resulting blizzard of a torn-to-shreds contract, Columbus gives his pewee characters a lesson in humanity. One of the movie’s central morality plays is the idea that, no matter how dependent on it we may become, there is more to life than money. Throughout the movie, the kids are subjected to an emotional roller coaster, the scene in which they seem to stumble upon Willy’s treasure, only to realise they’re standing under a wishing well, proving particularly significant. Rather than answering their hopes and dreams, the well acts as a window into reality and the monotonous, real-life tragedy that awaits them beyond their adventure. Not only does it allow them to view their situation through the sober eyes of adulthood, it inspires them to make one last push for freedom with the kind of heartfelt abandon that only a child can conjure.

When the kids finally do splash their way to a mysterious cave of gems and rubies, they immediately rejoice in their newfound opulence, but with the long-fabled Willy as his guide, Mikey grows to discover what is truly important. For the Goonies, riches represent freedom, perhaps the only thing in life other than love that transcends the prospect of wealth and the peace of mind it brings, but through Willy they realise it is more about the journey than the spoils, and the newfound understanding that journey brings.

Director: Richard Donner

Screenplay: Chris Columbus

Music: Dave Grusin

Cinematography: Nick McLean

Editing: Michael Kahn