On Saturday, a documentary about Russell Brand premiered in the United Kingdom. This documentary, the culmination of a yearslong investigation by the Times, the Sunday Times, and Channel 4’s investigative current affairs unit Dispatches, is hard viewing. Brand is accused of rape, sexual assault, and controlling, emotionally abusive behavior in a series of incidents between 2006 and 2013. One woman accuses Brand of raping her against a wall in his Los Angeles home, another of sexually assaulting her elsewhere in Los Angeles, and she alleges that he threatened to take legal action if she told anybody what happened. One of the alleged victims, known only as “Alice,” was 16 at the time of her relationship with Brand, then 30. (The age of consent in the U.K. is 16, but Alice believes that “it shouldn’t be legal for a 16-year-old to have a relationship with a man in their thirties.”) In an accompanying piece by the Sunday Times, Alice says she remembers arriving at Brand’s house in a taxi and that the taxi driver, after recognizing the destination, begged her not to go inside. She also says Brand once “forced his penis down her throat,” causing her to choke, and that she had to “punch him really hard in the stomach to get him off” her.

Brand denies all the allegations, claiming that the relationships he had during this period were “always consensual.” In a video posted to his YouTube channel the day before the documentary aired, Brand says, “Amidst this litany of astonishing, rather baroque attacks are some very serious allegations that I absolutely refute,” and accuses the investigation of having some other “agenda” at play.

The whole affair is bleak for several reasons, including some beyond the depravity of what he is accused of doing. Brand, one fears, is just the tip of a very large iceberg. The day before the documentary came out, Channel 4 announced it without saying who or what it was about. It’s well known in the U.K. what a vague Dispatches announcement means: Somebody famous is about to be exposed for wrongdoing. Once it was thought that it was a #MeToo–type revelation, and even after the rumor mill narrowed it down to comedy, dozens of different names were bandied around online by those in the industry. Depressing, too, is the fact that all of the usual suspects have rallied around to defend him: Andrew Tate, Elon Musk, Tucker Carlson, Alex Jones, and various right-wing figures in the U.K. Whether he knew this was coming is an open question, but he has certainly built up the right audience to go to bat for him now. In recent years, Brand has pivoted to YouTube, where he positions himself as a wellness guru, interviews contrarians about various conspiracy theories, and rails against the “mainstream media.”

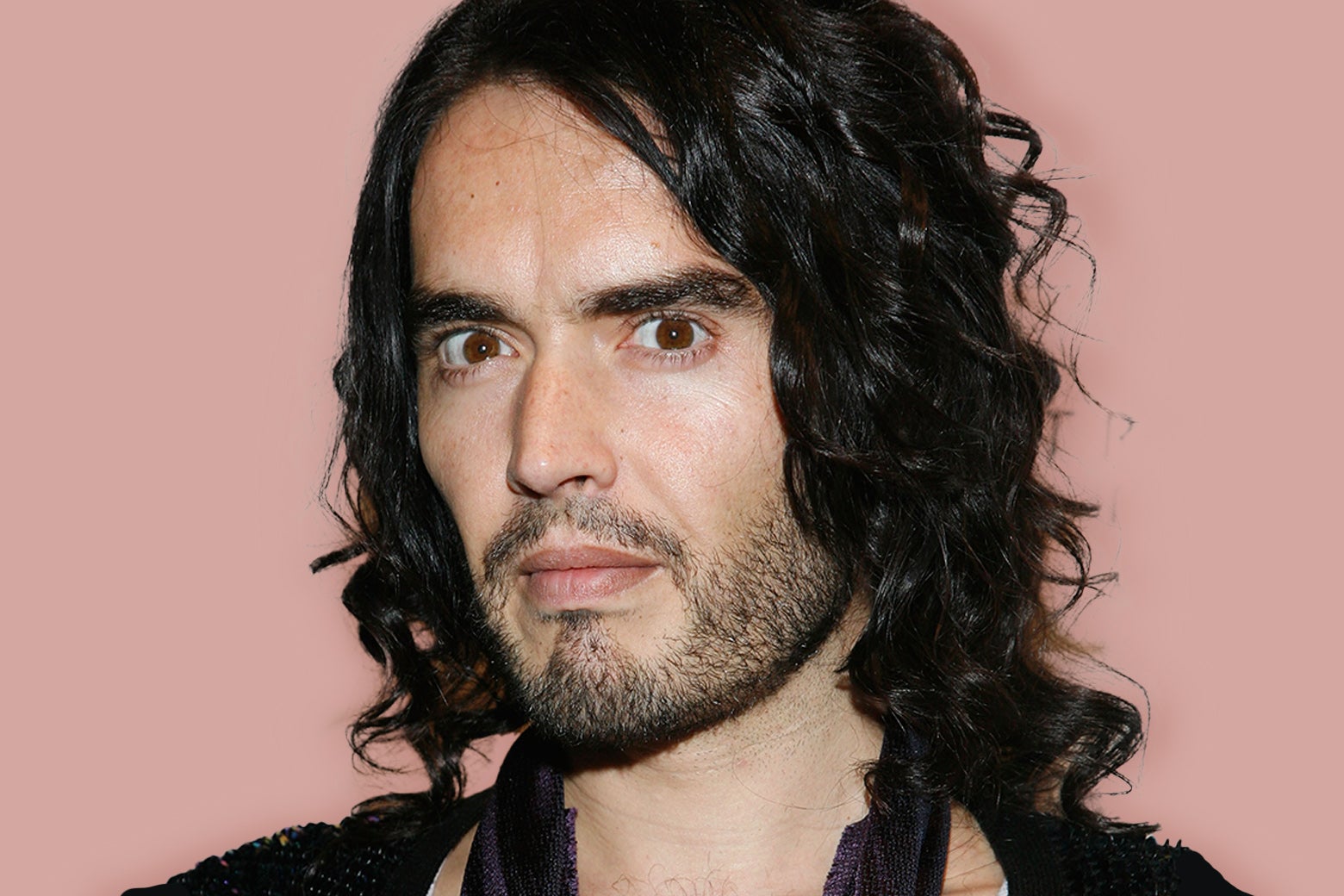

Russell Brand became known internationally in the late aughts and early 2010s for his roles in films like Get Him to the Greek and Forgetting Sarah Marshall, as well as his slightly perplexing marriage to Katy Perry, but he was a household name in the U.K. a good deal before that. He was a stand-up, then picked up for TV hosting gigs, including on Britain’s most famous reality television show, Big Brother, and later had his own radio show on the BBC. He lost the BBC show in a scandal known as “Sachsgate,” in which he called up a British actor named Andrew Sachs and left voicemails describing how he had slept with Sachs’ granddaughter. The BBC aired the episode and received thousands upon thousands of complaints. He was a major player in the indie sleaze scene, which had its center in London’s Camden neighborhood, friends with everyone who was considered cool at the time. You couldn’t find better artifacts of that era’s style than pictures of Brand: back-combed hair, incredibly skinny jeans, ruffled shirts, silk scarves, pointed boots, a dandyish, grungy aura of sleeplessness and debauchery. And whether or not you liked him—and plenty of people did—you knew his name. He was a presence on television like no other: wildly flamboyant and pleasingly filthy-minded, an ostentatiously eloquent human flamingo who seemed transported not from Essex in 2006 but from some kind of Victorian apothecary.

The documentary has made a lot of people reflect on the grim zeitgeist that fostered Brand’s celebrity. Brand reached fame by being exhilaratingly disgusting and untamable, and he did it in a culture that celebrated those qualities. The British aughts were an odd time to be a young woman. There were topless teenagers in tabloid newspapers. One of these newspapers, the Sun, awarded an accolade called “Shagger of the Year,” which Brand himself won three consecutive times. A radio DJ called Chris Moyles offered live on air to sleep with the Welsh singer Charlotte Church once she had turned 16. Paparazzi photographers lay in the street outside Emma Watson’s 18th birthday party to get pictures up her skirt.

Brand wrote books, performed stand-up, and gave interviews about what he called his “promiscuous” lifestyle, describing himself as a recovering sex addict. I balk at the idea that just because, in his comedy shows, he described doing things like choking women with his penis during blow jobs to the extent that their mascara runs, we should assume he forced those things on women in real life. It may not be to your taste or mine, but a stand-up routine is not a statement issued under oath. It is true, though, that the feeling here in the U.K. about the revelations has largely not been one of surprise. It is not surprising to those of us who grew up in the aughts that he might have been able to continue behaving in a predatory manner without anybody intervening. It is alleged that many people associated with Brand, including his management and the TV channels he worked with, knew about his behavior and did nothing. He was untouchable, both a product and figurehead of a culture of permissiveness about sexist attitudes. He seemed so far out ahead of any criticism of himself—admitting he was a narcissist and an addict and a lothario—that there wasn’t any point accusing him of being a bad person. He said so all the time.

And we loved him for it. The Dispatches documentary includes audio from Brand’s BBC radio show in 2007, during which he offers up his “very attractive” female assistant, naked, saying that she has to “greet, meet,” and “massage” anyone he demands. (The man he’s offering her to is Jimmy Savile, another BBC personality, who was revealed a few years later to have been a prolific sexual offender.) Listening back to this, I felt strange. I remember listening to the show avidly at the time, when I was about 15. I remember this specific broadcast. I thought Brand was hilarious, daringly irreverent, clever. The show was full of discussions of women as little more than sex objects, and I don’t recall noticing, let alone caring. Watching the documentary, I felt sad primarily for Brand’s victims, but also for the girl I was then, and all of the other girls like me, who sat on the bus to school listening to stuff like this, who didn’t have the wherewithal to do anything with his misogyny but soak it up and laugh.