As published in Hong Kong Tatler, December 2013

“In art, truth is suggested by false means,” Edgar Degas once declared, and artist Yinka Shonibare’s work reveals some harsh realities about modern society: racism, inequality between colonising and colonised cultures, and the excess of a contemporary society increasingly on the verge of implosion.

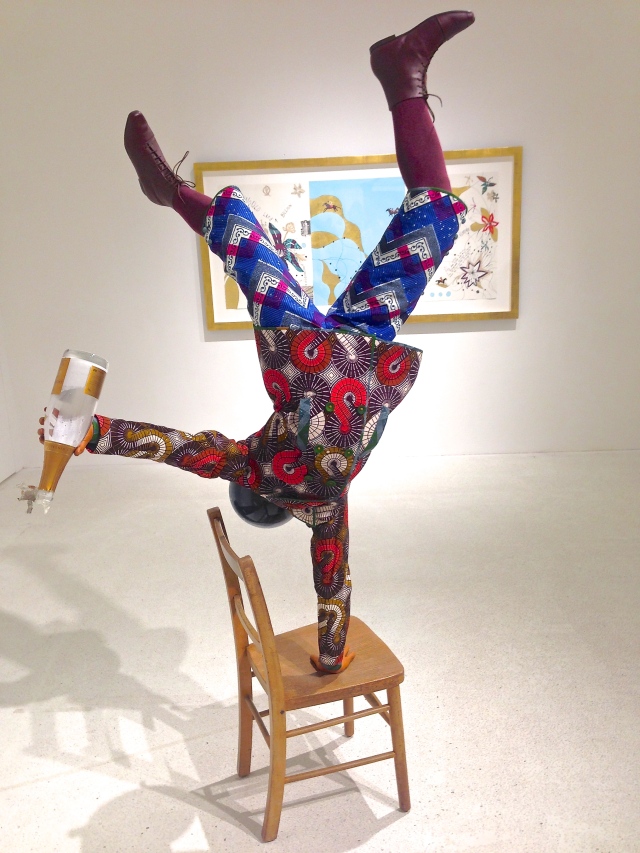

Works by the 51-year-old British-born, London-based Nigerian feature headless fibreglass mannequins dressed up in a whirl of brilliantly patterned batik fabrics, all whipped up into bustled Victorian costumes; or stuffed foxes, similarly attired, pointing shotguns at each other (the hunted now as the hunter); or a surreal dinner party with 14 headless mannequins seated at a table in animated discussion. Such whimsical, humorous and playful displays take the form of frozen tableau narratives, reiterated in Shonibare’s photographs, films and installations.

The textiles are the starting point to deciphering Shonibare’s work. He has used them so extensively that they have become an instantly recognisable visual identifier, and a clever device used to challenge stereotypes and assumptions about identity, culture and authenticity. On the textiles alone, at first glance one reads the works as products of an African artist, rooted in African tradition. But, as with Shonibare himself, the historical narrative woven through the works is culturally complex in many ways, and his pieces reflect not only his own hybrid nature, but also the reality of a global society.

While the fabrics he uses are worn and used in Africa, Shonibare initially discovered them at Brixton Market in London. A colonial invention that drew on Indonesian designs, such fabrics have actually been manufactured through an industrial process in the Netherlands since the 1880s. After the Dutch failed to sell them in Indonesia during the colonial period, the fabrics made their way to West Africa, where they are still used. They are both a fake and yet an “authentic” sign of African-ness, the perfect example of a multi-layered global identity and a canvas upon which Shonibare explores the myth of singular cultural identity. Whipped up into Victorian era-inspired costumes, a reference to the period in British history when imperialism and conquest of Africa was at its height, the works therefore juxtapose historic European style with the traditional African.

A critique of the extremes and frivolity of the imperial 18th and 19th centuries runs through Shonibare’s work – a strong metaphor for the excesses and luxury obsession of our time – while the history of colonialism is filtered through 20th-century fabrics. Recently, the artist exhibited his installation Fabric-ation, a tongue-in-cheek exploration of Britain’s imperial past and wealth built on the plunder of colonies, in Yorkshire Sculpture Park. It could as easily be a commentary on the injustices continuing today.

Shonibare’s Mr and Mrs Andrews Without Their Heads (1998), meanwhile, is a sculptural interpretation of Thomas Gainsborough’s painting Mr and Mrs Andrews (1750), and his The Swing (After Fragonard) (2001) appropriates Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s The Swing (1766) to explore aristocratic decadence. All the figures involved are decapitated – a reference to the beheadings that befell the aristocracy during the French Revolution, and a reminder of historical tensions between the ruled and the ruling. Though the references may be historical, the works are loaded with themes that resonate with contemporary audiences.

The genesis of Shonibare’s exploration of authenticity and identity lies in an anecdote so widely cited that it has become a part of Shonibare’s mythology. While studying art at London’s Goldsmiths College, Shonibare was asked why he didn’t focus on making “authentic African art”. “That comment, although it came from one teacher, was by and large society’s stereotyping. It was a reflection of the thinking that already exists within society,” he says via telephone from his London studio. The comment spurred him to examine the questions of cultural identity that have become a cornerstone to his art. “My work is trying to look at the world in a new way, particularly in the context of the United Kingdom. It’s a multicultural society, so I guess what I’m saying is that society is more diverse now, so why can’t we reflect that in the art that we produce?”

While Shonibare’s works challenge our stereotypes and assumptions, the artist has had to combat many such stereotypes and challenges himself. At the age of 18, he developed inflammation of the spinal cord, which left him with complete paralysis. Thirty years later, he has overcome a lot physically – he still suffers from partial paralysis and uses a wheelchair, but just as he has refused to be defined by cultural categorisation, so too has he refused to be defined by his disability.

To carry out his labour-intensive projects and meet the increasing demand for his work, Shonibare, like many conceptual artists, works with a team of collaborators, including costume designers, filmmakers, photographers and sculptors. “There’s this myth of the busy artist in his studio,constructing every part of their work, which is unrealistic,” he says. “It’s a curious thing that the issue of collaboration is never brought up with an architect. Nobody asks Zaha Hadid, ‘Why aren’t you building the bricks?’ The issue would never arise.”

Shonibare continues, “I have a busy studio. I started off painting by hand, but I wanted to explore and push the boundaries of my practice further, and I needed skills I couldn’t possibly have myself. I don’t know if I could have learnt how to make costumes, or even how important it would be to learn those skills. But in terms of the breadth of my ideas, it is really very broad and I don’t want certain skills to restrict the scope of my thinking.”

Ironically, though his works question the credibility and status quo of the establishment, Shonibare has also received some of the highest accolades and endorsements from the establishment. He has exhibited at the Venice Biennale and leading international museums; he was invited to create an installation for Documenta XI in 2002; he was made Honorary Fellow of Goldsmiths in 2003; and this year he was elected Royal Academician by the Royal Academy of Arts. Shonibare was appointed an MBE in 2004, which symbolically places him firmly on the inside. The irony of an artist who produces works critiquing imperialismreceiving an honour deeply rooted in an imperialist past is not lost on Shonibare. In an interview with Bomb magazine shortly after he received the MBE, Shonibare said: “It’s always better to make an impact from within rather than from without.”

In his first Hong Kong exhibition,’Dreaming Rich’, which runs until January 9 at Pearl Lam Gallery, the artist continues his exploration into power relations, looking at the excesses of the past two decades. In Champagne Kids, mannequins dressed in Shonibare’s trademark batik Victorian costumes hang off chairs and walls, swigging Cristal champagne. Another piece depicts a banker symbolically ejaculating with a shaken bottle of champagne. “I think the financial collapse in 2008 did highlight the excesses of the financial world, and also the subsequent impact on relatively innocent people who are not necessarily connected to that world, and the effects of irresponsible decisions on ordinary people,” Shonibare says. “The direct impact of this reckless behaviour of bankers was big.”

In a city where the disparity between the haves and have-nots is ever-increasing, and the flaunting of excess is often considered to be a virtue, perhaps there is no better place and time to take a moment and reflect on Shonibare’s powerful creations.

‘Dreaming Rich’ on until 9 January, 2014

Pearl Lam Gallery

6/F, Pedder Building, 12 Pedder Street, Central

+852 2522 1428

pearllamgalleries.com

Leave a comment