The Warhol Effect: We Are All Sons of Andy

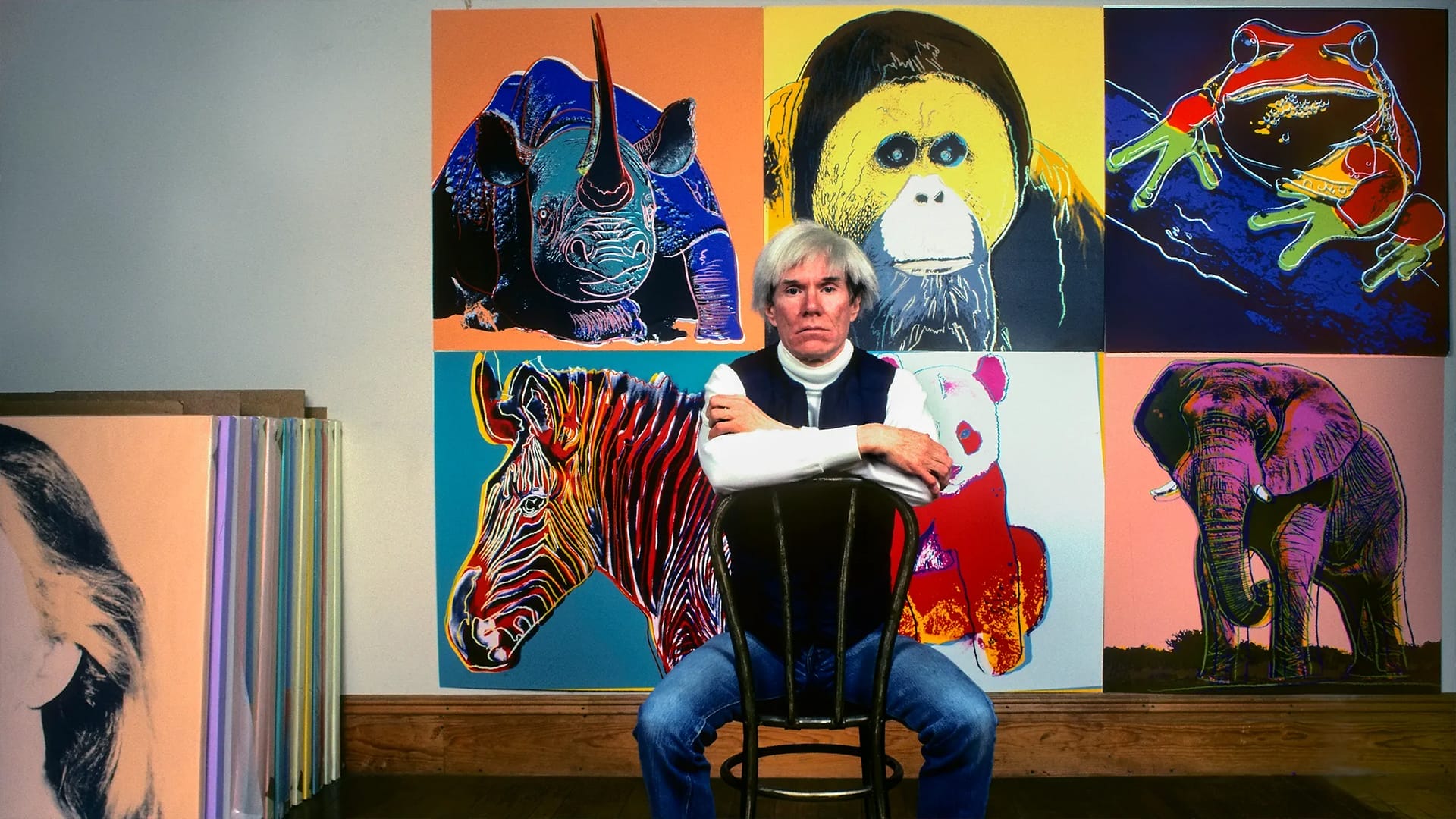

A Pittsburgh-born artist, Andy Warhol emerged as one of the most recognized artists in the 1960s New York art scene as he transcended the ordinary, transforming everyday objects such as Campbell’s soup cans and Coca-Cola bottles into works of art, challenging the very notion of what ‘art’ is.

While this might seem commonplace now, during Warhol’s time, it was nothing short of revolutionary. In an era where art was primarily reserved for the elite, often featuring lofty ideals and classic themes, this approach adopted by Warhol, at its core, democratized art. It reflects the belief that art can be found anywhere, not just in galleries or elite circles.

And today, we can see connections between this approach and the rise of digital art platforms even more clearly: Blockchain technology, which underpins much of the new world of digital art, allows artists of all backgrounds to create and sell their work without the need for traditional gatekeepers. A shift towards a more decentralized and inclusive art world that recalls Warhol’s early ambitions of making art universally accessible.

In addition, Warhol’s work is characterized by another concept that resonates profoundly with the digital realm — reproducibility. In today’s digital world, digital files can be copied indefinitely, with the additional benefit of blockchain technology assuring the authenticity of the ‘original,’ yet intertwining the concepts of replication and authenticity, as Warhol’s art did decades ago.

Warhol, often seen as a visionary, didn’t just predict the future of art; in many ways, he designed it. His work laid the foundation for the innovations we are witnessing today in the digital art ecosystem.

In the sections to follow, we’ll delve deeper into these connections, drawing a clear line from Warhol’s innovative approach in the 20th century to the digital art landscape of the 21st century.

Democratization of Art

Warhol fundamentally believed in the universality of art. In a society where art often celebrated historical events, nobility, or religious themes, his focus on commonplace objects and celebrities was a deliberate challenge to the established hierarchy of the art world.

And this democratization wasn’t limited to the subject matter. In fact, Andy Warhol introduced the concept of mass production to art by using silkscreening in his work, allowing multiple copies of a single work to be made. This not only made art more comprehensible and affordable but also eroded barriers between the art world and the general public.

Digital Reflections: Today’s digital art scene, powered by blockchain technology, resonates with this approach as it is democratizing art access and ownership in unpredecented ways. Through dedicated platforms, artists, especially those marginalized or overlooked due to geographical, financial, or social barriers, can now directly reach their global audiences. Not to mention, the introduction of NFT-backed multiple editions, which in a similar way to Andy Warhol’s silkscreening process, also resonate.

NFT-backed art symbolizes not just a new form of ownership but also epitomizes a decentralized art scene, giving artists full autonomy, from creation to sale. A shift, that aligns profoundly with Warhol’s dream of a universally inclusive art world.

Success and the Digital Self

Warhol, with his keen insight into the emerging media landscape and consumerist culture of the 20th century, prophesied a world where fame would be both more attainable and fleeting.

With the advent of mass media, he envisioned a society where anyone, irrespective of their origins or status, could enjoy a brief stint under the spotlight. This sentiment is immortalized in a famous proclamation often linked to him as originally published for a 1968 exhibition of his work at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, Sweden — “In the future, everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes”.

Although there are also theories to the effect that this quotation may have been misattributed to Andy Warhol, it is nevertheless noteworthy that it resonates with his vision.

Digital Reflections: In today’s digital age, the proliferation of social media seems to validate this foresight, but with a twist, as social media platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube have leveled the playing field, transforming ordinary people into “celebrities” overnight. Today, “virality” is often equated with fame.

Yet, the digital art landscape offers a dimension Warhol might not have anticipated, as artists and creators today aren’t confined to transient moments of fame. On the contrary, the digital tools at their disposal empower them to achieve and maintain prolonged reach : they can foster a loyal audience of collectors, refine their artistry continuously, and carve out lasting legacies.

The transition from Warhol’s predicted “15 minutes” to a prolonged digital engagement captures the profound influence of technology on redefining our notions of success and artistic worth.

Redefining Artistic Value

As cited briefly above, Warhol’s exploration of the mundane wasn’t merely an artistic impulse, but a profound statement on what society deemed as ‘valuable’ art. This prompted a provocative question: can the commonplace be revered as art?

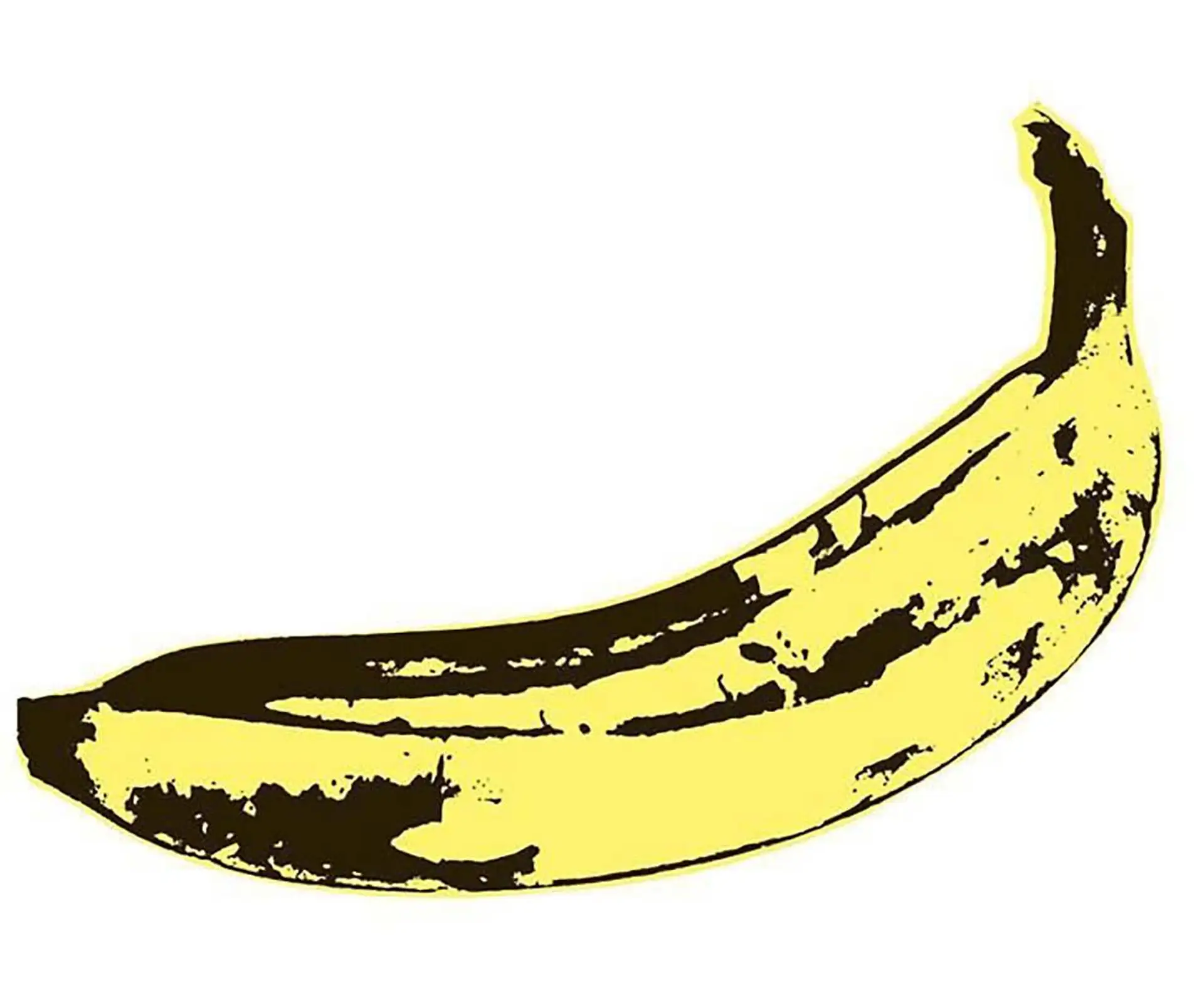

With surging consumerism and an evolving advertising landscape in post-war America, Warhol brilliantly captured the zeitgeist. Items like Campbell’s soup cans became symbols of a culture in flux, shaped by the engines of mass production and media. By spotlighting these objects in his work, Warhol challenged the very societal constructs of value and taste. After all, why shouldn’t a soup can claim the same artistic reverence as a revered Renaissance piece?

Digital Reflections: Fast forward to today, the digital age certainly mirrors Warhol’s time, but with its own unique nuances. As Warhol employed the novel print techniques of his day, modern artists use the tools of technology — coding, algorithms, and immersive realities — to craft experiences beyond traditional artistic confines, which similarly, was met with skepticism by the traditional art scene.

Skepticism, linked not only to value monetary-wise, but beyond. If Warhol’s soup cans spurred dialogues around consumerism and the criteria for artistic value,likewise, today’s digital pieces have sparked discussions on the very essense creativity, the meaning of authenticity, and the evolving contours of artistic expression in an interconnected digital ecosystem.

In addition, it is important to note how traditional art often leans on the principle of scarcity, where a one-of-a-kind piece commands higher value due to its irreplicability. Nonetheless, both Warhol’s mass-produced pieces and digital artists’ open editions defy this axiom, raising yet another compelling question: does art’s true value lie in its rarity, or in its capacity to evoke aesthetic and emotional connections?

Medium as a Message

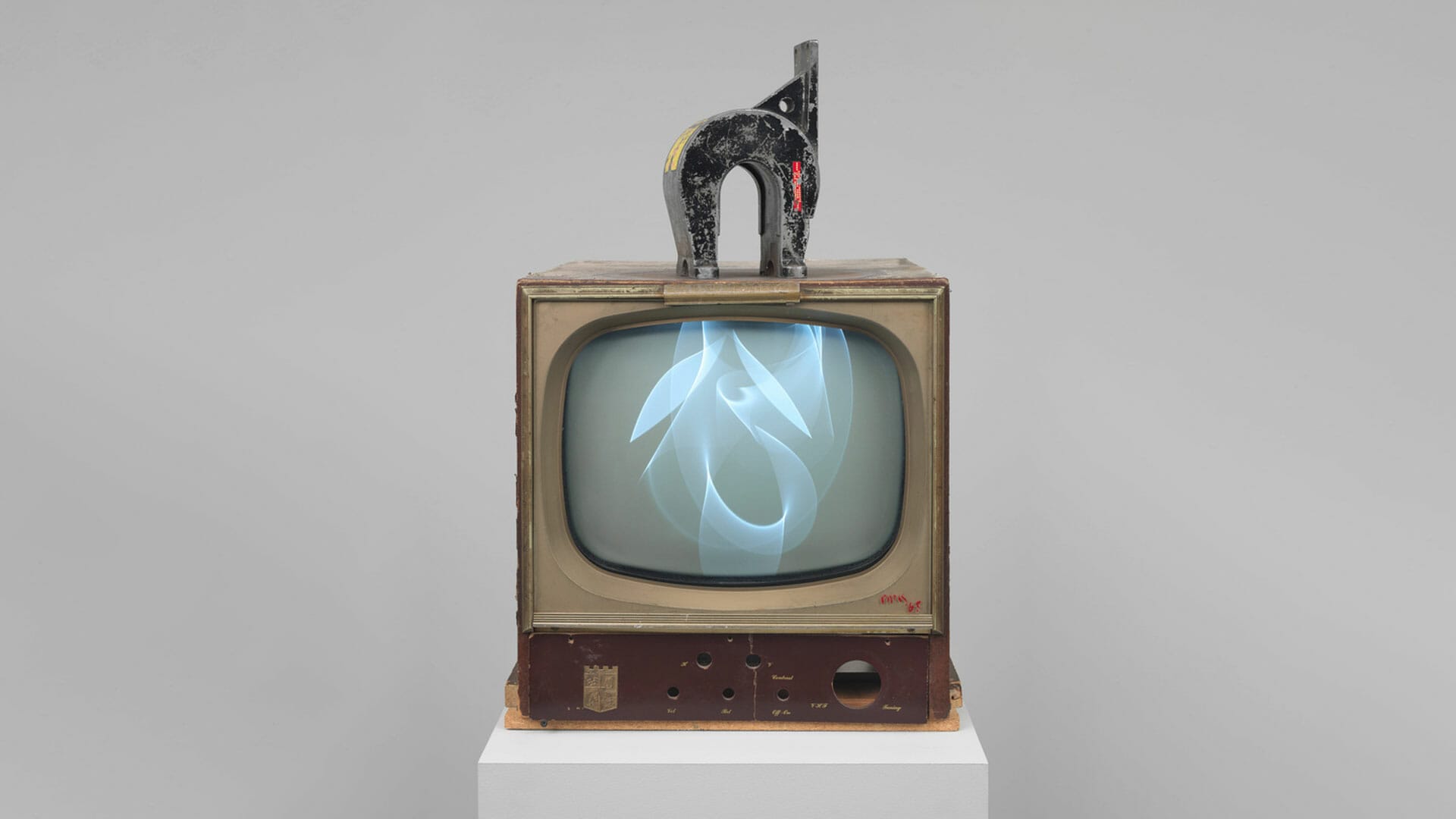

Warhol’s avant-garde approach to art was underpinned by his deep engagement with his chosen medium. The silkscreen printing method was not an arbitrary choice; it was a deliberate and inspired decision. Originally an industrial technique used for producing mass items like T-shirts and posters, Warhol’s adaptation of silkscreening for his art was symbolic of his larger commentaries on mass production and consumer culture. Each repetitive print, while similar, had its unique imperfections, echoing the fine line between the individual and the mass, the unique and the standardized.

For Warhol, the medium wasn’t just a vessel for his vision—it was an intrinsic part of the message, contributing layers of meaning to the final artwork.

Digital Reflections: Today’s digital landscape offers artists an expansive toolbox, with each tool and platform carrying its own connotations. When a digital artist chooses to create using virtual reality, code-based generative art, or blockchain, it isn’t merely about the aesthetic or functionality. These choices also often embed their artworks with layers of contemporary socio-cultural and technological commentary.

Blockchain, for example, has transcended its initial utility as a secure transaction tool. When incorporated into art, it becomes a statement on decentralization against the backdrop of an increasingly centralized digital world — hence, the birth of Cypto-Art. It challenges notions of authority, originality, and value in the art world. In this way, much like Warhol’s silkscreens spoke to the issues of his time, modern platforms and technologies offer artists a dual canvas: one for their immediate art and another for the broader messages and critiques they wish to convey.

Authenticity and Replication

In the art world where singularity and exclusivity often drove value, Warhol’s approach to replication was both defiant and thought-provoking. By using the method of mass production, he subverted the art world’s sacrosanct notions of originality. His repeated prints of icons like Marilyn Monroe or the repetitive patterns of the Campbell’s Soup Cans weren’t just aesthetic choices. They were deliberate, critical reflections on consumer culture and the mechanized production systems of his time. Warhol wasn’t merely producing art; he was posing critical questions. In an era of mass production and consumerism, what does it mean for an artwork to be ‘original’? Can the very act of replication itself be a form of originality?

Digital Reflections: The dawn of the digital age has thrown these questions into sharper relief. In a realm where a single digital file can be copied countless times without any loss of quality, the notion of ‘original’ took on new complexities. But then entered blockchain technology, a system bringing the guarantee of authenticity amidst the sea of digital replication. With every work of digital art, there’s now a verifiable lineage and proof of ownership.

This modern conundrum, where every digital copy can be identical in quality to the ‘original’, harks back to Warhol’s provocations. In our digital epoch, we’re not just spectators; we’re participants in an ongoing dialogue between replication and authenticity, grappling with evolving definitions of originality, value, and artistry.

Warhol’s approach made people question what constitutes an “original” piece of art. If there are 50 identical prints of a Warhol piece, which one is the original? The same goes for open editions in the digital realm. Digital files can be reproduced perfectly, so the concept of an “original” becomes even more difficult to define.

Art as a Commodity

Warhol’s audacity extended beyond the canvas. In a world that often separated art from commerce, he unabashedly merged the two. For Warhol, art wasn’t some lofty pursuit devoid of commercial considerations. Rather, it was a symbiotic relationship where art influenced commerce and vice versa. His studio, aptly named “The Factory,” was a testament to this vision. It wasn’t just a space for creating art—it was a production hub, emblematic of the industrial age, where art was manufactured, much like any other product on an assembly line.

Digital Reflections: As we navigate the digital frontier, Warhol’s prescient views come alive in the realm of NFTs. The rise of the NFT marketplace has further blurred the lines between artistic expression and investment in the art market. Artworks in this space aren’t just static pieces to be admired—they are dynamic assets, subject to the changes of market demand.

And as digital art gets bought, sold, and speculated upon akin to stock market commodities, we are thrust into an ongoing debate—how do we balance the commercial and intrinsic values of art? A discussion that once again harks back to Warhol’s views on the intersection of art, value, and commerce.

In Conclusion

Among the vibrant tapestry of art’s expansive history, few figures stand out like Andy Warhol. His audacious approach to subject matter, medium, and the very institution of art, positioned him as a visionary, one whose provocations have resonated through the decades.

Today, as we navigate the complex corridors of the digital age, Warhol’s legacy emerges not just as a historical touchpoint but as a living, breathing guidepost. The rise of digital platforms, blockchain, and the subsequent democratization of art echo his advocacy for a more inclusive, reflective, and challenging art paradigm.

Where many see technological advancements as merely tools, the true insight lies in recognizing them as continuations of philosophical dialogues initiated by artists like Warhol.

His artworks, once perceived as radical, now read as prophetic, foretelling a world where art’s boundaries are forever fluid, its value perpetually debated, and its essence intrinsically tied to the societal currents of the time.

In a time when art is at the threshold of a new frontier, Warhol’s vision can guide us forward, reminding us that art, in its truest form, is both a mirror and a window—reflecting our present and reflecting the vast possibilities of the future.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

Anne Imhof: Breaking Boundaries

Anne Imhof, born in 1978, has emerged as one of the most compelling voices in contemporary performan

Distorted Visions: Artists Shaping Glitch Art

In the early 20th century, technological imperfections, exemplified by the white noise on a detuned

In conversation with Micol of Vertical Crypto Art

In this episode of Fakewhale Live, Jesse Draxler has a chat with Micol from Vertical Crypto Art. The