The main-line railway network in Berlin has insufficient capacity, for frequent long-distance and inter-regional services. That is not clearly visible at present, because services in Germany are far from ‘frequent’.

Berlin Hauptbahnhof: image by Dontworry under CC3.0 licence…

Even on the flagship ICE network, most lines have less than one train per hour. In fact, no ICE line has a 60-minute frequency over its entire length (2014). The high-speed sections (Schnellfahrstrecke) typically carry several ICE services, so combined frequencies are higher. At the edge of the network, however, frequencies are low, perhaps only a few trains per day. On the remaining ‘classic’ Intercity network, no single line has a 60-minute frequency. For comparison: the planned high-speed line north from London would carry 17 trains per hour. The Netherlands has high Intercity frequencies, with ten domestic Intercity trains per hour, through Schiphol Airport station. A 10-minute Intercity service is planned for several main routes.

Service frequencies are in any case lower in eastern Germany, than in the more densely-populated west. Around Berlin, the Regional-Express services usually run at a 60-minute interval: the remaining regional trains (Regionalbahn) usually less than that.

So there are fewer trains into Berlin, than you would expect given its population (4 million), its status as capital of Germany, and its geographic location. There are historical reasons: the post-war annexations brought the Polish border to 80 km from from Berlin, cutting eastern long-distance traffic to almost zero. The division of Germany did the same with traffic to the industrial west. Post-war refugee flows, and eastern population decline, concentrated population in western Germany. Nevertheless, the main factor is the central place of the car in German society, and the resulting lack of political commitment to rail transport.

And so the new main station in Berlin, Berlin Hauptbahnhof, is currently sufficient for all traffic. Not because it is too big, but because there are not enough trains. In fact, the station is smaller than its combined predecessors – Berlin once had 11 terminal stations. Most were destroyed by bombing in the Second World War

Ruin of the Anhalter Bahnhof, Bundesarchiv image…

A modern station with through platforms can process more traffic, than a 19th-century terminal station. However, even if the platform capacity is adequate, the rest of the infrastructure is not. Some of the lines into Berlin have not been touched since the Berlin Wall was built in 1961, or even since 1945. That too illustrates the low priority of rail transport in Germany. The new central station looks impressive: politicians find that more important, than whether trains can reach it.

Capacity issues in Berlin: north side

Typical capacity problems in Berlin were mentioned here earlier, in the proposal for an upgraded Prignitz line, Berlin – Neuruppin – Wittenberge, the old Kremmener Bahn. Historically, there were two main lines into central Berlin on the north side – Nordbahn and Stettiner Bahn. The Kremmener Bahn and the local line Heidekrautbahn branched from the Nordbahn, about 5 km from this station – so there were four northern routes into Berlin.

Trains used the terminal station Nordbahnhof. It was built by the Stettiner Bahn, and originally called the Stettiner Bahnhof, until 1950. The name Nordbahnhof was originally used for a separate freight station. In 1903, the approach tracks were re-aligned, to allow interchange with the ring line, Ringbahn. All tracks now ran parallel through the station at Gesundbrunnen, even though that meant two right-angled turns.

Gesundbrunnen in 1906: public domain, via Wikimedia…

When Berlin was divided, this route was disrupted. In combination with the new Hauptbahnhof project, Gesundbrunnen station was reconstructed, and services restored by 2005. The northern Ringbahn has become an approach line for Berlin Hauptbahnhof (Pilzkonzept).

The current arrangement is similar to the 1903 layout, with Berlin Hauptbahnhof replacing the function of the old Nordbahnhof. Trains make a right-angle turn, pass through Gesundbrunnen, make another right-angle turn, and approach the main station from the north. However, the old Nordbahnhof had separate approach tracks, and they have disappeared.

Gesundbrunnen has ten platform tracks, but west of the station there are only two tracks, for all trains except the S-Bahn. The S-Bahn itself has four exit tracks on the western side, for north-south and Ringbahn traffic. However, when the planned second north-south line is built (S21), it will also share the S-Bahn tracks eastward, and the platform tracks at Wedding station – inevitably reducing capacity.

Gesundbrunnen: 10 tracks in, 6 tracks out…

For optimal capacity, there should therefore be eight tracks between Gesundbrunnen and Wedding, instead of four. That is the only way to separate east-west and north-south trains passing through Gesundbrunnen.

At present the issue is academic, because there are so few trains. In fact, there are no trains at all over the old Nordbahn – because the mainline tracks have still not been reinstated. There are no regional trains from the Kremmener Bahn, because there are no tracks for them either. And there are no regional trains from the Heidekrautbahn, because its tracks inside Berlin have not been reinstated either.

East of Gesundbrunnen, the Ringbahn is well connected to the Görlitz line, via new platforms at Ostkreuz. When the reconstruction of Ostkreuz station is complete, that would be a useful route toward the new Berlin Brandenburg Airport (BER, formerly BBI), although no such service is planned.

The connection to the other eastern radial lines, toward Lichtenberg and Karlshorst, is inadequate. There are flat junctions at both ends, and with the Lichtenberg – Ostkreuz curve, and there are single-track bottlenecks. At present that is also a theoretical issue: there are no regular train services anyway.

Spandau line capacity and design

The same issues recur on other approaches to Berlin: tracks abandoned for 50 or 60 years, insufficient capacity, and design faults.

The north-western approach to Berlin Hauptbahnhof also uses the Ringbahn. The main lines from Hannover and Hamburg converge at Spandau: trains continue east along the Ringbahn, and then make a right-angle turn south into Hauptbahnhof. Again this replicates the historical layout – the new station has approximately the same location, as the old Lehrter Bahnhof and Hamburger Bahnhof.

The tunnel into Berlin Hauptbahnhof: middle tracks from Gesundbrunnen, side tracks from Spandau, image by Falk2 under CC3.0 licence…

Again there is a grade-separated junction, so that some trains can go to Hauptbahnhof, while others continue toward Gesundbrunnen. But again, it can not operate to full capacity, because the line from Spandau does not have four tracks over its entire length. There are six tracks into Spandau, but only four tracks onward, over the Havel bridge, and two of them diverge toward Charlottenburg.

On the Ringbahn tracks toward Hauptbahnhof, there is one intermediate station, Jungfernheide. Regional trains stop here, but there are no through tracks for fast trains, another design error. (There are four tracks available at Jungfernheide, but two are not connected to the Spandau line). The connections to the western section of the Ringbahn are also inadequate.

On the Ringbahn tracks toward Hauptbahnhof, there is one intermediate station, Jungfernheide. Regional trains stop here, but there are no through tracks for fast trains, another design error. (There are four tracks available at Jungfernheide, but two are not connected to the Spandau line). The connections to the western section of the Ringbahn are also inadequate.

And again, the new north-south S-Bahn has its own exit tunnel, but it connects to the existing platforms at Westhafen station. There will be four tracks into this station, but only two tracks out. That will be a problem for any extension of the S-Bahn west to Spandau.

The northern Ringbahn simply does not have the capacity for the function assigned to it in the Pilzkonzept. The same is true for the east-west line through Berlin Hauptbahnhof, the Stadtbahn.

Capacity on the Stadtbahn

The Berliner Stadtbahn is an east-west line, on brick viaduct through the historic centre of Berlin. It was opened in 1882 to connect to six radial lines. It also passed the old Lehrter Bahnhof and Hamburger Bahnhof, offering additional connections. The line was built with four tracks, with local and long-distance traffic separated from the start. The local tracks were electrified in the 1920’s, the first ‘S-Bahn’ line.

A four-track viaduct through a city centre is inevitably constricted by surrounding buildings. The alignment has many curves and S-bends. Space for the stations was also limited. Such a line would not be built today.

Stadtbahn at Hackescher Markt: image by H0tte, public domain…

The line is clearly obsolete. When Berlin Hauptbahnhof was built, the logical option was to replace it by an east-west tunnel – but there was no money for that. However, maintaining and using a low-quality line also costs money – probably more in the long run. The curved alignment itself restricts speed, and increases the risk of delays. With only two tracks, there is no separation of regional and long-distance trains, and at Alexanderplatz they share one island platform.

At the western end, the line is accessible from the Spandau and Potsdam lines, with a grade-separated junction at Westkreuz. These lines were not left to rot, because they were the main routes into West Berlin, when Germany was divided.

At the eastern end, at Ostbahnhof, the Stadtbahn is connected to five platform tracks. However, they are only directly connected to the Niederschlesisch-Märkische Eisenbahn, the current main line to Poland. The other connections were abandoned during the division of Berlin, when east-west train traffic was minimal. The current reconstruction of Ostkreuz station allows for only a single-track connection to Lichtenberg, on the former Ostbahn main line. (The Görlitz line is accessible via the outer ring line BAR).

South of Hauptbahnhof

The main lines from Magdeburg, Halle and Dresden originally had three terminal stations: Potsdamer Bahnhof, Anhalter Bahnhof, Dresdener Bahnhof. They were built beside each other, at the southern edge of the city centre. In principle, the four-track tunnel into Berlin Hauptbahnhof should allow it to replace their function. However, the new Hauptbahnhof is still not fully connected, to the three historic lines into Berlin.

Only the Anhalter Bahn toward Halle has been entirely restored. To reach the Dresden line, trains use the Anhalter Bahn, and then the outer ring line BAR. Restoration of main-line tracks, on the Dresden line inside Berlin, has only just entered the public consultation phase.

Reconstruction of the Potsdam main line (Stammbahn) has been under discussion for 20 years, without any progress. Apparently the design of the north-south mainline tunnel allows for a grade-separated junction with the Stammbahn, but further on, the regional train station at Potsdamer Platz reduces capacity, since it has no through tracks.

More tracks on the radial lines

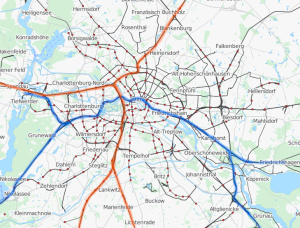

There are currently 11 main lines and 3 regional lines into Berlin. One regional line (Neukölln – Mittenwalder Eisenbahn) has been entirely abandoned. Some of the lines are duplicate routes, and it is also possible to create new link lines between them, allowing more effective distribution of services. Nevertheless, capacity on the radial lines is generally insufficient for high service frequency.

Only five of the main lines have a parallel S-Bahn line, to beyond the outer ring line (BAR). Only the Hannover main line has four tracks, as it crosses the BAR. If other S-Bahn lines were extended, then trains could run non-stop for about 25 km out of Berlin. If all trains can run at line speed – probably about 150 km/h – then capacity would be maximised. Further from Berlin, additional tracks will be needed on some lines, otherwise regional and freight trains will obstruct high-speed services.

Again these capacity problems are invisible at present. If there is only one ICE every two hours, and one regional train per hour, then two tracks is enough. Upgrading of several radial lines was proposed here earlier:

- conversion of the former Preussische Ostbahn out of Berlin, to a high-speed line Berlin – Riga. That would require new separate fast tracks, from Berlin Ostbahnhof to Lichtenberg, and probably four tracks east of Strausberg.

- new high-speed sections between Berlin and Rostock

- new high-speed sections between Berlin and Hamburg

- extra tracks on the Hannover line and connection to Nauen

That is an indication of what might be done, on the other radial lines. Obviously, these proposals assume a much greater frequency of services, of all types. That would certainly exceed the combined east-west and north-south capacity, at Berlin Hauptbahnhof.

Adding capacity inside Berlin

Inside the built-up area of Berlin, the first logical option is to upgrade the northern Ringbahn. If all the bottlenecks were removed, that would create an east-west route with its own tracks, from Spandau to Ostkreuz via Gesundbrunnen. Upgrading would be controversial, because it would require demolition of housing in Gesundbrunnen.

The improved northern Ringbahn could be used for regional and interregional services. All services would be by electric trains, which means that some lines outside Berlin must be electrified. The most logical pattern of services is from north-west (Spandau) to south-east (Frankfurt and Cottbus lines). To improve connections, a new link could be built between those lines. It could cross the Spree towards Karlshorst, or run between Schöneweide and Köpenick stations, partly parallel to the S-Bahn. With this new link, all trains can run through Ostkreuz, before turning south-east.

The western and southern Ringbahn can also be upgraded for regional trains. However, they do not offer the same logical and direct routes, as the Northern Ringbahn. The alignment is also sharply curved in places. At present, it carries no passenger trains. The new Südkreuz station, which is the main interchange on the southern Ringbahn, has no platforms for regional trains.

Südkreuz…

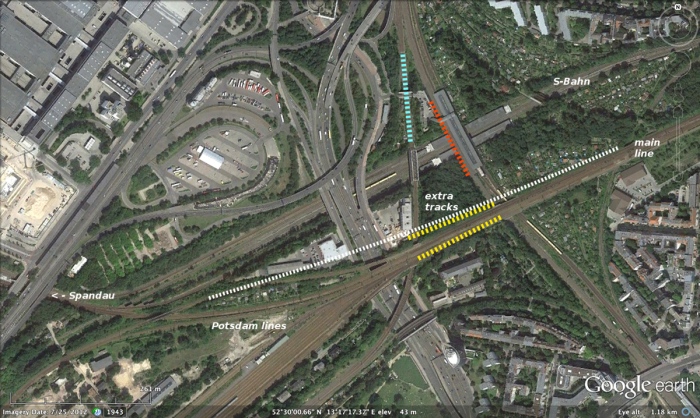

Regional trains from Spandau can reach the southern Ringbahn via the western Ringbahn. There would be no intermediate stations until Westkreuz, with new regional platforms alongside the S-Bahn station (shown in orange). To improve connections, regional trains from Potsdam via Wannsee should also stop at Westkreuz. They would have their own separate platforms (shown in yellow), replacing Charlottenburg regional station.

Click to enlarge: Westkreuz…

It is not logical for Potsdam trains to turn south-east onto the Ringbahn, since a restored Potsdamer Stammbahn offers an alternative route. They might use the western Ringbahn toward Gesundbrunnen: there is a connecting curve, but with little space for platforms (shown in blue). Equally, it is not logical to connect the Ruhleben link line to the southern Ringbahn, since the western Ringbahn offers an alternative route.

On the southern Ringbahn, regional trains from Westkreuz would stop at new platforms at Südkreuz and Hermannstrasse. The only good connection east of Hermannstrasse is to the Görlitz line, and therefore potentially to the new airport. However, that route is well served by the extension of S-Bahn line S45.

Connections to the airport: map by Robert Aehnelt under CC3.0 licence…

The eastern section of the Ringbahn, toward Ostkreuz, is of little use to regional trains. However, the utility of the southern Ringbahn can also be improved by a Köpenick link, which would allow regional trains to run from Südkreuz and Hermannstrasse to Erkner.

New tunnels

More radical options are a second north-south tunnel, a new east-west tunnel, and a second main station.

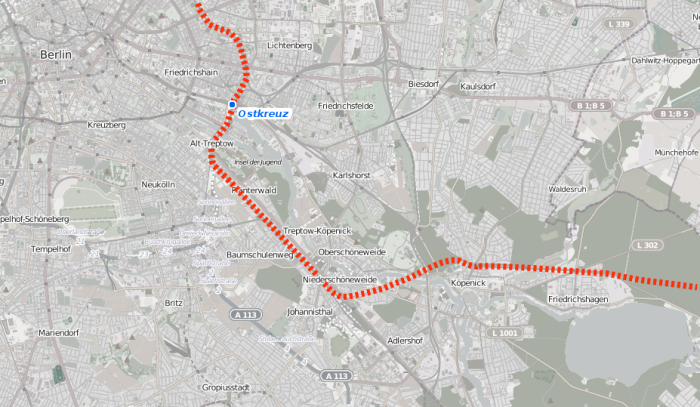

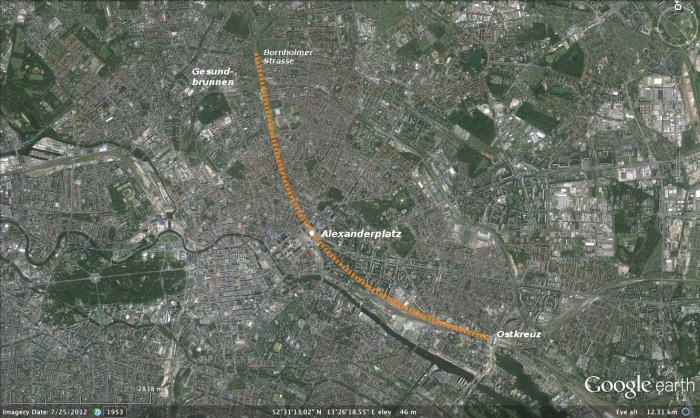

There are several possible options for a new north-south tunnel. An alignment between Bornholmer Strasse and Ostkreuz would maximise new approaches to central Berlin, and compensate for the design errors around Gesundbrunnen. It would connect the two main northern lines (Nordbahn and Stettiner Bahn), to the main eastern lines (Ostbahn and Niederschlesisch-Märkische Eisenbahn). An extension under the Spree could also connect it to the Görlitzer Bahn.

The tunnel would be about 8 km long. From the northern portal at Bornholmer Strasse, it would follow the alignment of the old Nordbahn freight yard – still free of buildings, because the Berlin Wall followed the railway here. At the southern end, the tunnel would climb alongside the existing railway toward Ostkreuz. The long approaches are necessary, because only a deep tunnel can pass under central Berlin. The tunnel would allow trains to pass quickly through Berlin, but also serve a city centre station. The only logical station site is at Alexanderplatz, at the eastern edge of central berlin. To avoid the U-Bahn and deep foundations, the station would probably be under the Alexanderstrasse.

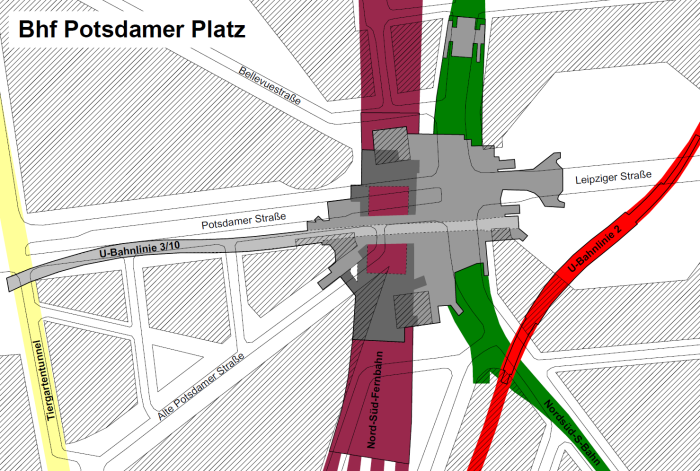

A new east-west tunnel to replace the Stadtbahn, would be at least 12 km long, and possibly 16 km. Again it could only run in deep tunnel under central Berlin, and requires long approaches. The east portal would probably be at Ostkreuz, or possibly at the old Görlitzer Bahnhof. The west portal would be at Westkreuz, or even at Ruhleben – or both. The shortest alignments would run south of the city centre, but that makes interchange with the north-south main line difficult. The optimal location for an interchange station is at Potsdamer Platz station, but it seems impossible to build a new east-west station, under all the existing tunnels here.

The tunnels at Potsdamer Platz: map by Zuzien1 under CC3.0 licence…

An east-west tunnel south of the city centre was planned, before and during the Second World War. It is seen as part of Hitler’s plans for a grandiose capital city, Welthauptstadt Germania, but the proposed alignment was quite modest. About 4 km long, it would have linked the Görlitzer Bahnhof to the Anhalter Bahnhof, with four intermediate stations. (Despite their megalomania, Hitler and Speer did not plan a main-line rail tunnel under Berlin, nor a single central station).

A new east-west tunnel is a precondition for a second main station. Given the difficulty of a large new underground station, it could have two new stations, one at each end. The only logical western site is at Westkreuz, which would maximise tangential connections. Its only U-Bahn connection, however, is the planned U3. A new eastern main station could be built just west of Ostkreuz, or on the site of the old Görlitzer Bahnhof, now a park. Again, the Görlitzer Bahn could be connected to the Frankfurt line, with a Köpenick link line.

The complexity and scale of the project make an east-west tunnel unlikely, even if the money was available. An upgraded northern and southern Ringbahn could carry many east-west regional and inter-regional trains, relieving the Stadtbahn. By reserving the Stadtbahn for longer-distance services, and closing the regional stations at Charlottenburg and Alexanderplatz, it can also be more effectively used. (There is, after all, a parallel S-Bahn). By improving approach capacity, the existing north-south tunnel can also be more intensively used, but additional north-south capacity still seems preferable.