The Federal Reserve has the power and authority to use the words “Federal Reserve note” to turn paper into money.[1] That power is part of the original functioning of the Fed and is enshrined in the Federal Reserve Act of 1913. Specifically, the Act ordered the production of $5, $10, $20, $50, and $100 (but not $1) Federal Reserve notes.

Once the notes were issued, banks and bankers (or anyone else) who held them could exchange the notes for gold or other U.S. currency.[2] Provisions of the Federal Reserve Act[3] were intended to make it easier for the new central bank to control how much money was in the economy, making the Federal Reserve note a more “elastic” currency—that is, a currency that can be adjusted in response to changes in the economy.[4]

In the 105 years since the passage of the Federal Reserve Act, things have changed: You can’t redeem paper money for gold anymore, and the $1 Federal Reserve note is the most common U.S. bill in circulation.[5] Major shifts in the economy and banking industry, both nationally and globally, and in U.S. law have led Federal Reserve notes to their modern versions.

When Federal Reserve notes debuted in 1914 (when the 12 regional Federal Reserve Banks opened), they were just one more option in the American currency market. Other parties issuing currency were the U.S. Treasury (which issued United States notes, silver certificates, and gold certificates) and nationally-chartered private banks (which issued national bank notes secured by U.S. bonds).[6] Some of these were legal tender—money that can be used to legally discharge any debt—and Federal Reserve notes technically weren’t. The Federal Reserve Act specified that the notes could be used to pay “taxes, customs, and other public dues” without saying anything about private debt.[7] There was so much competition[8] working against the new notes that in 1916 the Board of Governors had to firmly advise its regional Banks to stop circulating existing gold certificates and national bank notes and to instead use the new Federal Reserve notes (which the Banks had to pay the Bureau of Engraving and Printing to produce):

[The Board] hopes, therefore, that your bank will not let a desire to save a small expense influence it in this respect and that whenever it can issue Federal Reserve notes it will do so, thereby helping to concentrate gold certificates in the vaults of the Federal Reserve Banks and to put in circulation currency of an elastic character, which will be withdrawn automatically as soon as the demand for it ceases.[9]

Over the next few years, Federal Reserve notes continued to circulate and slowly gain traction. In 1918, with the passage of the Pittman Act, silver coins were taken out of circulation and new $1 Federal Reserve notes and Federal Reserve Bank notes (issued by the individual regional Federal Reserve Banks) were authorized.[10] The act also authorized other necessary denominations, and in 1918 the Federal Reserve began issuing larger denominations: $500, $1,000, $5,000 and $10,000 notes. These were used primarily for bank-to-bank transactions. All of these, along with their smaller-denomination brethren, were significantly larger than the bills we have today—about an inch longer in height and width.[11]

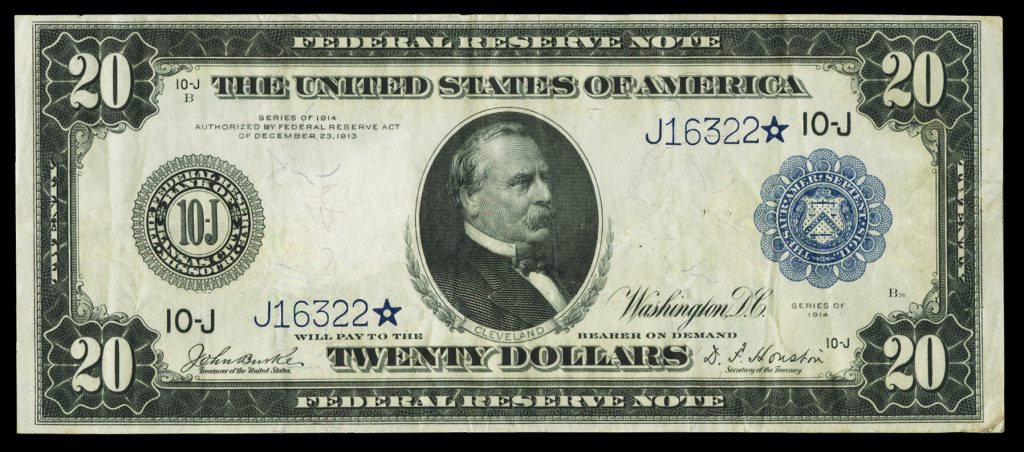

Federal Reserve note, series 1914. From 1914-1929, President Cleveland was on the $20 and President Jackson on the $10. Image courtesy of the Eric P. Newman Numismatic Education Society via the Newman Numismatic Portal at Washington University.

Unfortunately, the combination of lots of denominations and multiple sources of currency led to a serious counterfeiting problem. (A quick look at circular letters sent to banks in New York in the early days of the Fed shows multiple new counterfeiting warnings a month.) In response to this, and in an effort to keep printing costs down, in 1929, the Treasury called for the production of new, smaller notes (the size we use today). The smaller size was applicable to Federal Reserve notes and all other currency, including national bank notes issued by individual banks.[12] Printing designs were also standardized, making counterfeits easier to spot.[13]

Even with more standardization, many different kinds of paper money were still legal tender, and the Federal Reserve still issued a mix of its own notes along with United States notes and silver certificates that it did not produce.[14] For the Federal Reserve to fulfil one of its main jobs, to “furnish an elastic currency,” the multiplicity of currency and Federal Reserve note redemption for gold couldn’t continue for long. Currency changes made in response to the economic and financial crisis of the Great Depression were the beginning of the end of the gold standard in the United States[15]: As part of the banking holiday of March 1933, in which all banks in the country were forbidden to open for business for an entire week,[16] President Roosevelt issued an executive order banning the hoarding of gold, which was quickly made law as part of the Emergency Banking Act of 1933. Three months later, Federal Reserve notes were finally designated legal tender (along with all other U.S. currency) by a joint resolution of Congress.[17] The following year, Congress passed the Gold Reserve Act of 1934, amending the Federal Reserve Act, transferring the Fed’s gold to the Treasury, and causing Federal Reserve reserves and deposits to be held not in gold, but in gold certificates.[18] This combination of legislation made redemption of Federal Reserve notes for gold both a legal and a practical impossibility.

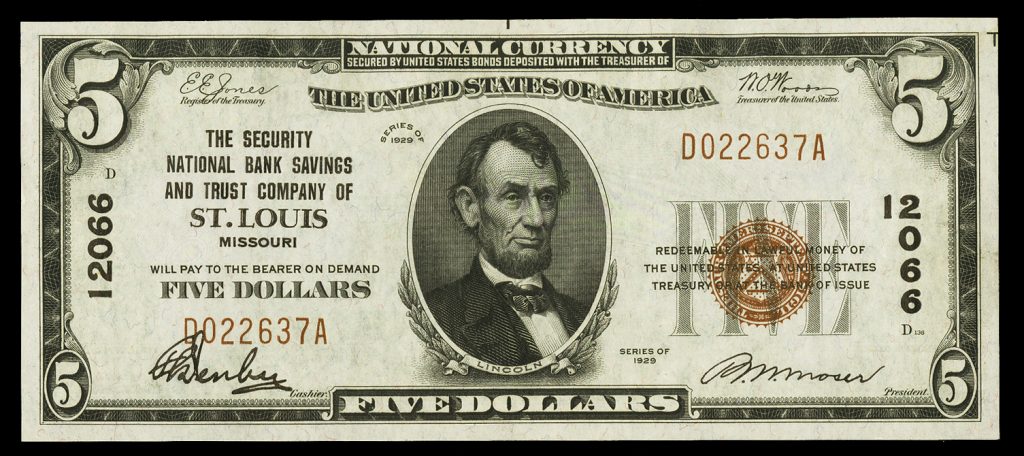

National banks continued to issue their own notes until 1935; most were destroyed at that time.[19] Any remaining national bank notes are still legal tender but are likely worth far more than their face value. This example is a note from the Security National Bank Savings and Trust Company of St. Louis, 1929. Image courtesy of the Eric P. Newman Numismatic Education Society via the Newman Numismatic Portal at Washington University.

Federal Reserve notes stayed more or less the same for the next few decades. Some cosmetic changes crept in: In 1949, the $20 was updated to bring the engraving of the White House on the reverse up to date; in 1955, Congress passed a law mandating the words “In God We Trust” on all currency,[20] a change that would roll out over the next few years. In 1963, however, a fundamental change was made to the U.S. cash supply: In June of that year, Congress passed a law repealing the silver purchase acts and authorizing the issuance of $1 and $2 Federal Reserve notes, thus making all U.S. paper money fiat currency.[21]

The Federal Reserve notes of series 1963 included the new $1 bill (but not the authorized $2) and reintroduced existing bills with the new motto. In 1966, the $2 United States note was discontinued, making those $1 notes even more attractive for everyday cash needs. In 1969, the Fed stopped issuing the large denomination bills ($500 and larger), which had not been printed since 1945. (Although rare, some of these large bills do still exist.) Two years later, the Federal Reserve became the U.S. currency when all other United States notes (predominantly $1 bills) were discontinued in January of 1971.[22]

Since then, the Federal Reserve note has changed very little. In 1976, in honor of the bicentennial, the $2 bill was reintroduced as a Federal Reserve note featuring Jefferson’s portrait. (Though uncommon, they are still in circulation.) In 1996, redesigned Federal Reserve notes debuted, partially to discourage counterfeiting in the era of color photocopying.[23]

Throughout all of these cosmetic and not-so-cosmetic changes, the issuance and circulation of currency has been one of the core functions of the Federal Reserve for over a hundred years. For a deeper dive into the history of the Federal Reserve note, search Fed publications on FRASER.

[1] U.S. Currency Education Program. “Journey to Circulation.”

[2] U.S. Congress. Public Law No. 43, 63d Congress, H.R. 7837, Federal Reserve Act. December 23, 1913.

[3] W.P.G. Harding. “The Federal Reserve Note, Its Functions and Limitations.” From an address before the convention of the Ohio Bankers Association, Columbus, OH, September 5, 1918.

[4] For more on the Fed’s elastic currency, see Dave Wheelock. “The Fed’s Formative Years.” Federal Reserve History, November 22, 2013; and Mark Carlson and Dave Wheelock. “Furnishing an ‘Elastic Currency’: The Founding of the Fed and the Liquidity of the U.S. Banking System.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, First Quarter 2018, 100(1): 14-44.

[5] Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. “Currency in Circulation: Volume.” As of December 31, 2017.

[6] Bureau of Engraving and Printing. “History of the BEP and U.S. Currency.”

[7] See the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System FAQ “What is lawful money? How is it different from legal tender?“

[8] E.E. Cummins. “The Federal Reserve Bank Note.” Journal of Political Economy, October 1924: 526-542.

[9] Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. “Federal Reserve Note Policy.” Federal Reserve Bulletin, October 1916: 10.

[10] Cummins.

[11] This and many other dates in this article are from the following: U.S. Currency Education Program. “From the Colonies to the 21st Century: The History of American Currency.”

[12] George L. Harrison. “New Small-Size National Bank Notes.” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Circular No. 937a, October 24, 1929.

[13] U.S. Currency Education Program. “The History of American Currency.”

[14] See George L. Harrison. “Reduced-Size Currency.” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Circular No. 915, May 24, 1929.

[15] Gary Richardson, Alejandro Komai, and Michael Gou. “Roosevelt’s Gold Program.” Federal Reserve History, November 2013.

[16] Robert Jabaily. “Bank Holiday of 1933.” Federal Reserve History, November 2013.

[17] U.S. Congress. Joint Resolution 73-10. 73d Congress, June 5, 1933.

[18] For more information on the history of Fed’s gold reserves, see the 1968 article “The Gold Cover” by Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond economist Joseph C. Ramage.

[19] See the following: Warren E. Weber. “Government and Private E-Money-Like Systems: Federal Reserve Notes and National Bank Notes.” Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta CenFIS Working Paper 15-03, August 2015. “Annual Report of the Comptroller of the Currency.” October 1935, Table 30, footnote 2.

[20] U.S. House of Representatives. “The Legislation Placing ‘In God We Trust’ on National Currency.” History, Art & Archives: Historical Highlights.

[21] “Fiat money” is money not backed by a commodity. See the “Currency and the Fed” lesson from our economic education team for more about how our currency system works.

[22] U.S. Treasury. “Resource Center: Legal Tender Status.” January 2, 2011, update.

[23] Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. “Where Is All the U.S. Currency Hiding?” Economic Commentary, April 15, 1996.

© 2018, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.

@FedFRASER

@FedFRASER