Setting the Stage—Pictorialism vs Straight Photography (All Photographs are Lies)

This week I dive into the origins of toxic gatekeeping in street photography culture, identifying its roots in a hundred year old beef between two of photography’s earliest movements: pictorialism and straight photography.

Last week I found myself upset at a certain popular way of framing street photography as needlessly gatekeeping, and perhaps even intellectually bankrupt. And then I channeled that unease with that definition into a broader thesis—that all photographs are lies, or more accurately, that there is no such thing as straight photography.

I don’t have an academic background in art—rather, my background is philosophy. So my specialty is teasing out and questioning assumptions, which is what this series of essays aims to do. But I'm learning my art history as I go, and it’s super fascinating.

So, let’s do a little stage setting. The argument I am trying to provoke has been had before, the first iteration of it starts about a hundred years ago between pictorialists and practitioners straight photography (because “straightist” doesn't work as a word, I guess?). Let's take a moment to get familiar with what’s come before.

Pictorialism

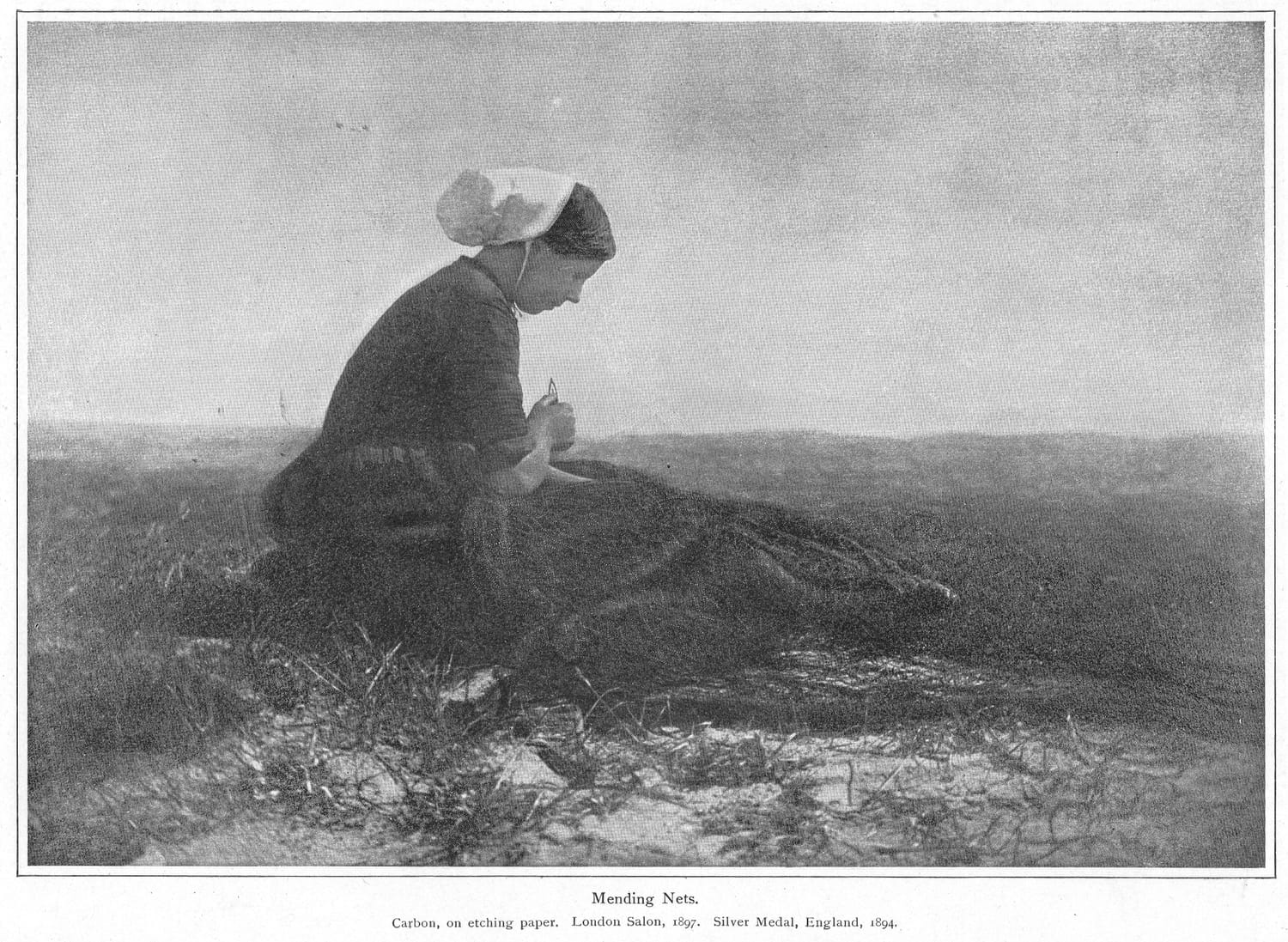

Pictorialism one of the oldest photographic movements, popular from the late 19th to early 20th centuries, sought to create first and foremost works of art by photographic means. Indeed, when photography was new, there was a prevailing sentiment that photographs could not be art. Naturally, many photographers such as Alfred Stieglitz (before his conversion to straight photography) disagreed, and set out to prove such critics wrong.

Imitating various painting styles, practitioners of pictorialism would happily avail themselves of whatever techniques of lighting, composition, lens manipulation, and darkroom technique to achieve the look they were going for. And that look was often one that bore only a passingly resemblance to the photographic subject. The selection of what to place in front of the camera was merely a part of the process of creating the work itself, and was not necessarily the actual subject.

Although pictorialism is clearly still in vogue in the early 21st century, certainly among the TikTok set who are just now discovering the many joys of adding imperfections to their lenses, few of the O.G. remain salient for contemporary photographers. There’s a reason for that. Pictorialism was also a reaction to the growing popularity of Kodak cameras, and pictorialists sought to set their work apart from the mere “snapshots” of the rapidly growing mass of amateur photographers armed with Brownies. You can imagine the 21st century parallel.

Straight Photography’s Critical Response to Pictorialism

If photography was to be recognized as a legitimate and distinct art form, it must be on its own terms. Straight photography, as popularized by Alfred Stieglitz (after his conversion from pictorialism) and (more famously) by Ansel Adams, is a response to to pictorialism that emphasizes the kind of image that can be created when you perfect your equipment and technique.

Pictorial photography had run its course, the thinking went, and managed only imitations of painting. So, rather than capture the mood of a scene, something that traditional painting was very good at, straight photography saw photography’s unique place as capturing a scene just as we see it with our eyes—to produce art that only a camera could.

To achieve this, straight photography sought to capture images with the minimum of mediation: optically perfect lenses, light meters for precisely measuring tonality, limiting darkroom editing to the removal of perceived imperfections, and the strict use of found subjects (as opposed to studio compositions).

The result was something genuinely new in art: Images that highlighted the natural beauty of the found world, unfiltered by embellishment or interpretation.

The Straight Photography Legacy

Pictorialism had largely faded away by the mid-twentieth century, and the straight photographic approach came to define how most of us understand what photography is: Representational, rather than interpretive. A good photograph is one that offers a compelling subject and composition, with the bare minimum standing between the viewer and the viewed. Behold trends like #nofilter and film sprockets. The photographer who boasts they never crop. The upset that revelations of heavy editing can trigger. The insistence that smartphones with their opaque image enhancing algorithms can never qualify as real cameras, let alone be used for street photography. The absolute outrage (on purely aesthetic grounds) that AI-generated photo-like images can induce. This is our status quo, and though dominant it is of course not how everyone thinks about photography.

The Pictorialists Strike Back

Obviously, this is the most superficial treatment of the history of straight photography possible. There’s so much more to it than I can cram into 1,000 words. I can only encourage you to dig deeper for yourself if you find this interesting.

Next week, I want to dig deeper into the last of the pictorialists, Adolf Fassbender, and his poignant but largely unheeded critique of the straight photography movement. Look forward to it!

Support this blog

If you enjoy reading this blog, I encourage you to consider purchasing a book or print to show your support. And if you're into analog photography, check out my new mobile app Crown + Flint.