CAA News Today

David Raizman (1951–2021)

posted by Allison Walters — Feb 25, 2021

David Raizman speaks at CAA’s 108th Annual Conference in Chicago at Columbia College Chicago. Photo: Stacey Rupolo

The CAA Board of Directors and staff wish to express our profound sorrow at the passing of David Raizman. We are deeply grateful that he was part of our lives. During his time at CAA as interim executive director, treasurer, and member of the board, we had the privilege to witness firsthand what an exceptional person he was. His commitment to CAA, leadership acumen, generosity of spirit, scholarship, and, most important, his great kindness lifted all who had the good fortune to know and work with him. He is and will be truly missed.

David Seth Raizman, a historian of medieval Spain and modern design, died on Monday, February 22, 2021, in Abington, Pennsylvania. He was 69. An esteemed scholar and educator, he was also widely admired as an unusually kind and generous colleague and an all-around mensch.

Raizman earned his AB (1973), MA (1975), and PhD (1980) in art history at the University of Pittsburgh. He wrote his dissertation, “The Later Morgan Beatus (M.429) and Late Romanesque illumination in Spain,” under the direction of the late medievalist John Williams. The two became lifelong friends, and Raizman made a point of visiting Williams nearly every time he traveled to Pittsburgh over the next 35 years, until Williams’s death in 2015.

Raizman married his beloved wife Lucy (Salem) in 1974. After completing his dissertation, Raizman accepted a tenure-track position at Western Illinois University in Macomb, Illinois, in 1980. In 1989, the by-then family of four returned to their home state of Pennsylvania when Raizman accepted a position at Drexel University in Philadelphia. Raizman retired from Drexel’s Antoinette Westphal College of Media Arts and Design as a Distinguished University Professor in 2017.

Raizman initially specialized in medieval Spanish manuscripts, and he continued to publish occasional articles on medieval Spanish topics into the mid-2000s. However, a second and arguably more significant chapter in his scholarly career began in the 1990s, after he agreed to teach a course on the history of modern design at the request of Drexel’s design faculty. He taught the first iteration of his combined history of graphic design, industrial design, and decorative arts course in 1992. After struggling to find a suitable textbook to assign his students, he decided to write his own. Raizman published the first edition of History of Modern Design in 2003 and a second edition in 2010. It is now a standard text in design history courses around the world. Raizman was preparing the third edition at the time of his death.

Teaching design history and writing History of Modern Design proved formative events in Raizman’s career. During the last two decades of his life, he worked tirelessly to help advance the field of design history in the United States. He became a stalwart member of the College Art Association (CAA) affiliated society Design Studies Forum, organized design history sessions at CAA conferences, and organized and presented in sessions about design history at three consecutive National Association of Schools of Art and Design (NASAD) annual meetings in the 2010s. He coedited Objects, Audiences, and Literatures (2007) with Carma Gorman; he coedited Expanding Nationalisms at World’s Fairs (2017) with Ethan Robey; and, most recently, he wrote Reading Graphic Design History: Image, Text, and Context (2020), a collection of essays on seven oft-misunderstood items in the graphic design history canon. He regularly published articles, book reviews, and entries in reference works on topics ranging from nineteenth-century World’s Fair presentation furniture to mid-twentieth-century aluminum chairs to twenty-first-century “DesignArt.” And he mentored many emerging scholars in the field of design history, most notably by organizing and leading a month-long National Endowment for the Humanities summer institute with Carma Gorman at Drexel University in July 2015.

In addition to contributing to the fields of art history and design history as a scholar, Raizman shouldered major service roles at his university and in national scholarly organizations. At Drexel, he chaired two departments for a total of ten years and served twice as associate dean and twice as interim dean of his college. At the national level, even after his shift in scholarly focus from medieval art to modern design, Raizman served as treasurer of the International Center of Medieval Art (ICMA) from 2015 to 2018. In that role, he led the organization to adopt a socially responsible investment model that realigned ICMA’s financial profile with its intellectual commitments. When CAA announced later in 2018 that it was seeking a new treasurer, Raizman once again volunteered his services. And in 2019, when CAA sought an interim executive director, Raizman agreed to take on that role, but only on the condition that CAA not pay him a salary. Commuting from Philadelphia every other week to his shared apartment in New York, he held the post of interim executive director as a full-time, unpaid volunteer for nine months in 2019–20. Those who worked with him in the CAA office and on the CAA board during that time often noted his patience, kindness, and diplomacy as he helped guide the organization through a period of transition. After the hiring of executive director Meme Omogbai in March 2020, Raizman continued on as treasurer, conscientiously presenting his last report to the board just two weeks before he died.

Outside of academe, Raizman was an avid tennis player, a talented bluegrass and blues guitar player, and a passionate sports fan, especially of the Pittsburgh Steelers and the Philadelphia Phillies. He also loved classical music and opera. He doted on his young grandson, enjoyed refinishing furniture, and collected Arts and Crafts ceramics, Art Deco posters, and modern furnishings.

Raizman was preceded in death by his parents, Albert and Adele, and his brother, Richard. He is survived by his wife of 46 years, Lucy Raizman; daughter Rebecca Newman, son-in-law David Newman, and grandson Jacob Orion Newman of Los Angeles; and son Joshua Raizman and daughter-in-law Sommer Mateer of Havertown, PA.

Contributions in David Raizman’s honor and memory may be directed to CAA or the Westphal College of Media Arts and Design at Drexel University.

—Carma Gorman, with kind assistance from David’s daughter, Becky Newman; family friend Ilene Raymond Rush; and colleagues Matthew Bird, Elizabeth Guffey, Jim Hopfensperger, Jennifer Kaufmann-Buhler, Victoria Pass, Alexa Sand, Gunnar Swanson, and Christopher Wilson.

Deadline Extended: Join the CAA Annual Conference Committee

posted by Allison Walters — Feb 12, 2021

Attendees at CAA’s 108th Annual Conference in Chicago. Photo: Stacey Rupolo

CAA invites nominations and self-nominations for one at-large member of the Annual Conference Committee to serve a three-year term. The Annual Conference Committee also invites applicants for Annual Conference Co-Chairs, two at-large members of the Annual Conference Committee that serve a two-year term. The terms begin late March 2021.

The Annual Conference Committee, working with the CAA staff, selects the sessions and shapes the program of the Annual Conference. The committee ensures that the program reflects CAA’s goals for the conference, namely, to make it an effective place for intellectual, aesthetic, and professional learning and exchange; to reflect the diverse interests of the membership; and to provide opportunities for participation that are fair, equal, and balanced. Committee members also serve to support sessions comprised of individual papers and projects where a formal chair has not been identified.

The Chair(s) oversees the Council of Readers and reports back to the Annual Conference Committee on session topics, including identifying possible areas of content and interest to members that are missing from the submissions received. With CAA staff, the Chair(s) recruits Council of Readers members to read, review, and rank proposals. The Chair(s) shapes the content to the Annual Conference from the submissions as reported back by the Council.

As a member of the Annual Conference Committee the Chair(s):

- Works with CAA staff and oversees the execution of the overall goals of the conference

- Ensures that the Annual Conference reflects the goals of the Association

- Makes the Annual Conference an effective place for intellectual, aesthetic, and professional learning and exchange

- Reflects the diverse interests of the membership

- Suggests conference content based on member interest

- Assists in scheduling the variety of chosen sessions, workshops, talks, etc.

- Proposes ways to increase conference participation and attendance

- Proposes new initiatives for the conference

- Proposes candidates for distinguished speakers

The Annual Conference Committee meets three times a year:

February – during the Annual Conference to examine and discuss the operational aspects of the conference which recently concluded and ideas for the upcoming conference;

May/June – on a virtual call to review the recommendations by the Council of Readers for the upcoming Annual Conference;

October – on a virtual call to review final plans and any existing changes for the Annual Conference up to two years out.

Please send a 150-word letter of interest and a CV to Mira Friedlaender (mfriedlaender@collegeart.org), CAA Manager of Scholarly Content and Programs, by March 8, 2021, 11:59 PM (EST) (deadline extended).

In Memoriam: Robert L. Herbert

posted by Allison Walters — Dec 22, 2020

Robert L. Herbert

We are saddened to learn of the passing of Robert L. Herbert, a visionary in art history and extraordinary teacher to many. He received CAA’s Distinguished Lifetime Achievement Award for Writing on Art in 2008. He passed December 17 of a stroke at 91.

Robert L. Herbert

In an extraordinary career spanning more than sixty years, Robert L. Herbert was remarkably consistent in a practice that has come to define the social history of art, which he described as “the moral and passionate … search for what paintings and drawings meant in the artists’ time.”1

As an undergraduate at Wesleyan University in the late 1940s and early 1950s, he was fascinated by the history of science, an interest that encouraged his study of color theory in his dissertation on the nineteenth-century French artist Georges Seurat, completed at Yale University under the direction of George Heard Hamilton in 1957. By that time, Herbert had already been inspired by the work of Meyer Schapiro, who encouraged his lifelong commitment to socialism as a framework for political and intellectual development. Proud of his roots in a working-class New England family, Herbert resisted the formalist bias of his training, although he readily acknowledges a debt to those who taught him to look carefully at works of art and to appreciate the importance of technique and pictorial structure. From the beginning he always insisted that “the stuff of ordinary daily life should enter into art history,” and made it his goal “to restore the flesh of real painters and their culture to the bones of style and form.”

A desire to balance respect for the artist’s distinctive modes of representation with a socially and historically grounded reading of subject matter was a salient feature of Herbert’s research, which focused, for example, not only on the color and facture of paintings by Seurat and other Neoimpressionist artists, but also on the distinctive subject matter and the politics of their art. Recognizing that the prevailing view of Seurat tended to privilege his large-scale paintings, Herbert trained attention on his drawings in a book published in 1963; yet he also continued to explore the meanings of Seurat’s paintings, organizing a major retrospective exhibition on the hundredth anniversary of the artist’s death in 1991 as well as another, Seurat and the Making of “La Grande Jatte,” that was devoted to his most celebrated painting in 2004. In fact, many of Herbert’s most innovative and important contributions to the history of art have been made in the context of exhibitions, which require careful attention to individual objects in addition to the presentation of a unifying conception of the whole. For his first foray into this genre of scholarship, the 1962 exhibition Barbizon Revisited, Herbert wrote a catalogue that won CAA’s Frank Jewett Mather Award and precipitated a renewed appreciation of the work and historical significance of mid-nineteenth-century landscape painters such as Corot, Millet, and Rousseau, among others. His ambition for the exhibition was expressed in terms that convey his dedication to a particular kind of art-historical practice: “The purely historical treatment of art is bloodless. The real heritage of Barbizon art is in the paintings, and their vitality must be experienced in our viscera. Otherwise works of art are documents to be assessed, catalogued, and filed away. But there is a proper use of history, namely, to prod us into discoveries which release our imagination and permit us to rise to the realm of true poesis. An historical evaluation of Barbizon art will only have value if it succeeds in doing just this.”

Just as the study of Seurat’s drawings prompted Herbert to look carefully at Millet’s drawings and other work in articles and exhibitions of the 1960s and 1970s, so Seurat’s paintings eventually led him to the work of Fernand Léger, whom he considers to be Seurat’s descendant and a great practitioner of the craft of painting. Thus although Herbert’s scholarly reputation is bound to his work on nineteenth-century French painters—he has written books on Monet and Renoir, a survey devoted to the leisure subjects of the Impressionists, as well as the publications mentioned above on Seurat, Millet, and the Barbizon School—he has also produced significant scholarship on early-twentieth-century modernism. His first contribution to that field was an edited volume of ten essays, Modern Artists on Art, published in 1964. This was followed twenty years later by a detailed study of the large, diverse collection of European and American modernist art from the Société Anonyme that Katherine Dreier had bequeathed to Yale at midcentury and that Herbert had explored for many years together with his students. Along the way, Herbert developed research he had undertaken as a graduate student into a book, published in 1972, on David’s Brutus and its political significance in the context of the French Revolution; his commitment to the social history of art was also evident in a volume of selected art criticism by John Ruskin that Herbert edited in 1964 and for which he wrote an eloquent introduction that provided a thoroughgoing reevaluation of Ruskin’s significance from a variety of perspectives, demonstrating his acute relevance to the social history of art that Herbert was in the process of articulating at the time.

It is impossible to summarize Herbert’s contributions to art history simply in terms of his scholarly production, impressive as that output has been. He has also been an inspiring teacher of undergraduate and graduate students, setting an example in countless ways that go well beyond his commitment to scrutinizing original works of art alongside archival resources of the most diverse kinds. In addition to imparting these indispensable staples of the trade, he maintained an extraordinary level of personal and professional engagement with his students, loyally supporting their ambitions and celebrating their achievements, whether large or small. Refusing to be impressed by conventional measures of status, in 1990 he acted on his commitment to feminism by relinquishing his position at Yale in order to join his wife, Eugenia Herbert—whom he has always described as his greatest intellectual companion—on the faculty of Mount Holyoke College.

As professor emeritus and living in South Hadley, Massachusetts, he discovered a passionate interest in the life and work of a mid-nineteenth-century female botanist and illustrator named Orra White Hitchcock. “I’ve taken the plunge,” Herbert has remarked, “into the world of American women’s diaries, into travel diaries, and into the history of geology and the natural sciences, embraced in the broader spectrum of American social and cultural history of the middle third of the nineteenth century. It’s a new world for me, and I have no regrets at giving up French art history!” Subsequently he turned to exploring the history of Mount Holyoke and curated several exhibitions with James Gehrt and Aaron Miller.

He died December 17 of a stroke at 91 and is survived by his wife of 67 years Eugenia (Fi); children, Tim, Rosie, and Cathy; their mates, Mara, John and Chris; six grandchildren, and a wealth of friends to whom he was immensely devoted as well.

International News: Letters from Asia Art Archive Under Lockdown (Part I)

posted by Allison Walters — Nov 10, 2020

The following article was written in response to a call for submissions by CAA’s International Committee. It is by John Tain, Congyang Xie, Michelle Wong, Cici Wu, and Noopur Desai, all researchers at Asia Art Archive.

Introduction, John Tain, Head of Research, Asia Art Archive

In the first few months of this year, one thing that became clear was how deeply divided the world remained and remains, even as globalization brought us all closer physically and virtually. There have been of course the many overt racist acts around the world, and also the less visible but no less insidious effects of structural racism on individuals and communities of color. There also remains plain ignorance reinforced by geography. In long distance calls and video meetings, it became clear that what people across Asia recognized right away as a cataclysmic life-or-death disaster remained literally and figuratively a faraway concern for many people in the United States and Europe—until it wasn’t anymore.

At Asia Art Archive (AAA), we have seen the drama unfolding firsthand in both Asia and North America. Our colleagues in Shanghai went into lockdown almost as soon as the news came out of Wuhan, with our main office in Hong Kong soon to follow. For those first few weeks, outpourings of concern, sympathy, and sometimes curiosity accompanied the daily news and dreaded case tallies. Then, as the pandemic spread, it was our colleagues in New York and then New Delhi who were hit, along with the rest of the world, and it became our turn to send support and supplies when possible. We had already been in the habit of meeting regularly on Zoom as a way to work across distances, but throughout these months, talking with one other online became about more than work. It became a way to bridge the chasms keeping us apart all the more now. It is in the spirit of those conversations that I have asked my colleagues to share their thoughts, as reminders that whatever the disparities, we must deal with this together.

The Pandemic and Politics, Congyang Xie, Research Associate, Asia Art Archive, Shanghai

In early February, two weeks after the shutdown of Wuhan due to the outbreak of the coronavirus, an article was published by Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek titled “Clear Racist Element to Hysteria over New Coronavirus.” Translated into Chinese and circulated through the social media platform WeChat, it quickly became one of the most widely shared texts among contemporary art practitioners in Mainland China. Žižek, who has built a large readership in China over the last decade, began by saying that “Some of us, including myself, would secretly love to be in China’s Wuhan right now, experiencing a real-life, post-apocalyptic movie set.” (https://www.rt.com/op-ed/479970-coronavirus-china-wuhan-hysteria-racist/)

More challenging statements followed. Unsurprisingly, there were all kinds of reactions within the art world, which amplified when more articles were published and circulated via WeChat by other Western thinkers who are more or less known to Chinese art practitioners, including Jean-Luc Nancy, Jacques Rancière, and especially Giorgio Agamben (Fig. 1). But the controversies around Žižek were particularly interesting. If Žižek’s text, as many have pointed out, disregarded the local context in China, the reading and sharing of the article in Chinese was also decontextualizing. The (re-)awareness of the very existence of intellectual borders that so many people tried hard to ignore may be one of the by-products of COVID-19.

Figure 1. Left: A WeChat account publishing translated articles by various Western philosophers regarding the pandemic. Middle: Screenshot of Žižek’s article published in Chinese. Right: Screenshot of an article by Chinese poet Xiao Yin, titled “The Wuhan City That Žižek Cannot Understand”. Photo provided by the author.

Reading the text in a literal way, Žižek’s fiercest critics denounced the philosopher as naïve, if not delusional, for saying the situation in Wuhan was desirable, for ignoring the real tragedy in Wuhan, and for being indifferent to the dead and to those who were still suffering. Such opinion is based upon a humanistic attitude. The most extreme camp, however, went so far as to reach a nationalist point of view, concluding that Westerners never understand what is happening in China, and that Western theories are irrelevant and not applicable to China’s problems.

Another group of critics, non-nationalists, with a more liberal mindset, were thus highly attentive to Žižek’s call for “a new form of what was once called Communism.” Based on modern and contemporary history of China, this group considers Communism as just the flip side of the coin of authoritarianism. Taking individual freedom as a priority, this group worried that the activity-monitoring technologies used by the government in the name of containing the epidemic would eventually normalize and strengthen total governmental control over society, even after the epidemic ends.

This critical attitude towards authority was shared by a third group of people, who would agree at least partially with Žižek, citing his words that “If there were people in China who attempted to downplay epidemics, they should be ashamed.” In fact, during the first days of the coronavirus outbreak, transparency from authorities was the strongest demand from all of China’s social groups. The protest reached a peak when Li Wenliang, the whistleblower doctor who was forced to keep silent by authorities, was reported to have passed away from the deadly disease on February 7. That night, lit-candle emojis were all over social media. In response to the event, artist Zhang Peili designed a minimalist set of two T-shirts, which are worn frequently by artists and visitors to exhibitions (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Online shop selling T-shirt designed by Zhang Peili. The text means “I understand.” Photo provided by the author.

The debates highlight the ideological conflicts in China that have only intensified under the pandemic, though more space would be needed to map the full spectrum of opinions. Perhaps what makes Žižek’s text so appealing to art practitioners in China in the first place is the claim that “there is, however, an unexpected emancipatory prospect hidden in this nightmarish vision,” even if people may have (mis)understood it in a thousand different ways.

Separate yet Together, Michelle Wong, former Researcher, Asia Art Archive, Hong Kong

Figure 1. Screenshot of news livestream, July 1, 2020. Photo provided by the author.

One evening in March 2020, when Hong Kong’s first wave of COVID-19 cases was subsiding, we sat in a friend’s studio to look at the image archive of an artist-run space. “100 Square Feet Park,” or the Park, as we affectionately call it, was once a storefront on Lai Chi Kok Road, facing busy traffic. The image we were looking at was of a documentary exhibition from the Umbrella Movement of 2014. A monitor was placed on a table facing the street level. Pedestrians walking by wondered whether the images shown in the monitor were live or documentary images. It struck me at that 2020 moment, as we looked at the image five years on, that I had forgotten how it felt when livestreaming news—of marches, of roads puffing with smoke, of sparks flying out from long tubes, of people in all sorts of uniforms running—was not yet a norm. I remember an inexplicably overwhelming feeling of looking at the nine images on the split-screen livestreaming for the first time, and I thought my simmering anger would rise to the boiling point if I saw one more Instagram post that attempted to theorize this over-mediation.

For some time now I have pondered the morbidity that is part and parcel of my vocation as a researcher at AAA. It is only half a joke when I describe my job as “talking to old(er) people and working on dead people stuff”. On various occasions I have described archives as haunted and haunting, trains for zombies, and repositories for art that could be undead. I still think about these things when I peer and squint at my computer screen while on Zoom/Jitsi/Skype. During the time leading up to the pandemic, and perhaps also during it (i.e. now), I think often about a generation of practitioners, many of them friends and colleagues who I have met through my work at AAA. I think of how these people, myself included, have knowingly or unknowingly committed ourselves to remembering other people’s lives. Everyone who tells stories of other people’s lives, in this case through dealing with their archives, is learning how to do so along the way, much like writers learning how to write. And as we remember these lives and tell these stories, our stories can become entangled with theirs. Sometimes, it is nice to know you can choose not to do it alone.

Apply to Join the CAA Annual Conference Committee

posted by CAA — Oct 01, 2020

Elpida Vouitsis presents at the 2020 Annual Conference in Chicago. Photo: Stacey Rupolo

CAA invites nominations and self-nominations for one at-large member of the Annual Conference Committee to serve a three-year term. The term begins February 2021, immediately following the 109th Annual Conference.

The Annual Conference Committee, working with the CAA Programs Department, selects the sessions and shapes the program of the Annual Conference. The committee ensures that the program reflects CAA’s goals for the conference, namely, to make it an effective place for intellectual, aesthetic, and professional learning and exchange; to reflect the diverse interests of the membership; and to provide opportunities for participation that are fair, equal, and balanced.

The Annual Conference Committee meets during the conference and at the call of the program chair and vice president for Annual Conference. Committee members also serve to support sessions comprised of individual papers and projects where a formal chair has not been identified.

Please send a 150-word letter of interest and a CV to Mira Friedlaender (mfriedlaender@collegeart.org), CAA manager of annual conference, by January 5, 2021.

Deadline: January 5, 2021

Affiliated Society News for September 2020

posted by CAA — Sep 01, 2020

Affiliated Society News shares the new and exciting things CAA’s affiliated organizations are working on including activities, awards, publications, conferences, and exhibitions.

Interested in becoming an Affiliated Society? Learn more here.

The Association for Textual Scholarship in Art History (ATSAH)

Announces two major changes: a new website: https://www.atsha.com/ and the formation of a new journal through Brill, A Journal of Contestations in the Arts https://brill.com/view/journals/para/para-overview.xml?lang=en.

Publications:

Liana De Girolami Cheney, Lavinia Fontana’s Mythological Paintings: Art, Beauty, and Wisdom. London: Cambridge Scholar Press, 2020.

Liana De Girolami Cheney, “Botticelli’s Minerva and the Centaur: Artistic and Metaphysical Conceits,” Journal of Culture and Religious Studies Vol. 8, No. 4 (April 2020): 187–216.

BSA (Bibliographical Society of America)

- October 15: Applications due for the BSA’s Call for Program Proposals. The BSA sponsors lectures, workshops, conference sessions, and receptions which are bibliographical in nature. Only virtual events considered at this time. See https://bibsocamer.org/programs/bsa-programs/.

- September 8, applications due BSA’s 2021 New Scholars Program. Those who have not previously published, lectured, or taught on bibliographical subjects are encouraged to apply. New approaches and diverse perspectives welcome. International applicants and joint applications accepted. See https://bibsocamer.org/awards/new-scholars-program/.

- November 1, applications due: BSA Fellowships. To foster the study of books and other textual artifacts in traditional and emerging formats. See https://bibsocamer.org/awards/fellowships/.

- November 2, applications due: William L. Mitchell Prize for research on British serials. Supports bibliographical scholarship on 18th-century periodicals in any language within the British Isles, its colonies, former colonies, and occupied territories. See https://bibsocamer.org/awards/william-l-mitchell-prize/.

- Ongoing: Community Subtitling Project: The BSA provides free public programming, accessible through the BSA’s YouTube channel. We offer free one year memberships to all who submit complete translations of edited English transcripts of individual videos. A guide to editing English subtitles and to adding foreign language translations can be viewed here. La guía también está disponible en español, aquí.

- September 2020 (vol 114:3), The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America:

Articles

J. Christopher Warner, “Recovered Books: On the Contents and Fate of John Fowler’s Stock Left with Christopher Plantin”

Tara L. Lyons, “New Evidence for Ben Jonson’s Epigrammes (ca. 1612) in Bodleian Library Records”

Bibliographical Note

Minoru Mihara, “Recycled and Reincarnated Relics of Ancient Poetry: Editorial Practice in Percy’s Reliques”

Book Reviews

Proot, Goran, McKitterick, David, Nuovo, Angela, and Gehl, Paul F., eds. Lux Librorum: Essays on Books and History for Chris Coppens

Reviewed by Sandro Jung

Eggert, Paul. The Work and the Reader in Literary Studies: Scholarly Editing and Book History

Reviewed by Anna Muenchrath

Barker, Nicolas. At First, All Went Well … & Other Brief Lives

Reviewed by Daniel J. Slive

Eckhardt, Joshua. Religion Around John Donne

Reviewed by Georgina Wilson

SHERA

SHERA Publication Grant—Deadline: October 15, 2020

The Society of Historians of Eastern European, Eurasian, and Russian Art and Architecture (SHERA) is pleased to announce the SHERA Publication Grant. The $3000 grant supports the realization of publications of the highest scholarly and intellectual quality in the field of Russian, Eastern European, and Eurasian art and architecture. The grant is intended to offset the substantial production expenses associated with the publication of an art-historical monograph, edited volume, or exhibition catalogue. Book projects must have been accepted by a publisher in order to be considered. Funds may be directed toward production costs and does not fund research, writing, or editorial labor. Applicants do not need to be SHERA members to apply, but the recipient must join in order to accept the award. For more information about applying, see http://www.shera-art.org/grants/publication-grant.php.

SHERA Emerging Scholar Prize–Deadline: Oct. 15, 2020.

The SHERA Board is pleased to invite applications for the 2020 Emerging Scholar Prize. The Emerging Scholar Prize aims to recognize and encourage original and innovative scholarship in the field of East European, Eurasian, and Russian art and architectural history. Applicants must have published an English-language article in a scholarly print or online journal, or museum print or online publication within the twelve-month period preceding the application deadline. Additionally, applicants are required to have received their PhD within the last 5 years and be a member of SHERA in good standing at the time that the application is submitted. The winner will be awarded $500 and republication (where copyright allows) or citation of the article on H-SHERA. For more information about applying, see http://www.shera-art.org/grants/emerging-scholar-prize.php.

American Society of Appraisers (ASA)

The American Society of Appraisers (ASA) wishes to spotlight its Personal Property sessions and experts for the upcoming 2020 ASA International Conference to be held virtually online October 12-13. Click here to learn more.

ALAA (Association for Latin American Art)

Please note that this is a living document; if there is a resource that you would like to see included or corrected, please follow the link above and there is a hyperlink where you can submit suggestions/changes.

Society of Architectural Historians

The Society of Architectural Historians is accepting proposals for SAH 2021 Virtual Programs to be presented after the SAH 74th Annual International Conference in Montréal on dates/times between May 3–28, 2021. These programs will complement the regular conference programming and should differ from the paper sessions in both topic and organization. Submissions that address the current conditions of research, teaching, and scholarship are encouraged. Submit a proposal by September 14, 2020.

SAH is accepting applications for Membership Grants for Emerging Professionals. These awards are intended for emerging scholars, regardless of age or employment status, who are new to the field of architectural history or its related disciplines. The award consists of a one-year digital SAH Individual membership. Emerging scholars who are adjuncts or unemployed are encouraged to apply. Apply by September 15, 2020.

The SAH Nominating Committee seeks nominations and self-nominations for two officer positions of Treasurer and Secretary. As two of five officers with full voting rights on the Executive Committee and the Board, these positions are among the most important in SAH; the other officers on the Executive Committee are the President, First Vice President and Second Vice President. In close collaboration with the SAH Board and staff, the Executive Committee governs the Society, proposes policies and programs, and provides service to the membership. Serving in these capacities offers an opportunity to shape the Society’s and the profession’s future. Submit a nomination by September 30, 2020.

SAH will present the webinar “Disability Studies and Architectural History” on October 29, 2020. Presenters and participants will consider key concepts in research and pedagogical methods for integrating histories of disability and efforts to pursue disability justice in architecture. The discussion highlights the importance of disability activism as it relates to design. Registration is free and open to the public.

Association of Print Scholars

The Association of Print Scholars is happy to announce that Clare Rogan, Curator of Prints and Drawings at the Detroit Institute of Arts, has been elected as the APS Director-at-Large for a three-year term. Additionally, we would like to congratulate the APS Director-at-Large Jan Howard and APS member Tatiana Reinoza, PhD on their appointments to the National Advisory Committee of Artura, a project of Brandywine Workshop and Archives. Howard is the Chief Curator and Houghton P. Metcalf Jr. Curator of Prints, Drawings and Photographs at RISD Museum. Reinoza is the Assistant Professor of Art History and Latinx Studies at University of Notre Dame.

We are still accepting individual paper proposals for our 2021 CAA panel “The Graphic Conscience,” chaired by Dr. Ksenia Nouril, The Jensen Bryan Curator at The Print Center in Philadelphia. The session invites papers addressing transhistorical and transnational case studies of print as a tool for raising public consciousness.

APS is currently accepting submissions until January 31, 2021 for two awards. The first is the 2021 Schulman and Bullard Article Prize, which carries a $2,000 prize and is generously sponsored by Susan Schulman and Carolyn Bullard, both private print dealers. The second is the APS Collaboration Grant, which funds public programs and projects that foster collaboration between members of the print community and/or encourage dialogue between the print community and the general public. Further application information for the two awards can be found on the APS website.

SECAC

SECAC 2020

VCUarts is honored to host the SECAC 2020 conference as a fully virtual event beginning on November 30 and concluding on December 11, 2020. We are planning for more than 80 online sessions, round tables, and town halls at the 2020 conference. Additionally, we have exciting virtual programming for conference participants, including a keynote lecture by Valerie Cassel Oliver, Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and a virtual Juried Members’ Exhibition in collaboration with the Anderson at VCUarts. We are also excited to announce reduced registration rates for members and non-members. For more information, please visit https://secacart.org/page/Richmond. Questions regarding the conference should be directed to 2020 Conference Director Carly Phinizy, secac2020@vcu.edu.

SECAC at CAA

The SECAC affiliate session at CAA in 2021 will be chaired by William Perthes of the Barnes Foundation and Adrian Banning from Drexel University. They will oversee a selection of speakers on the subject of, “Arts and Humanities Multidisciplinary Education Collaborations.”

SECAC Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

SECAC stands in solidarity with our Black colleagues, students, and communities to affirm Black Lives Matter. SECAC must resist the legacies of racism and white supremacy in our organization and disciplines. Together, we can imagine and create a better world, united in the pursuit of justice, equity, and transformation. We invite you to share your confidential feedback by email to SECAC’s Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion committee at SECACaction@gmail.com, and join in the SECAC Town Hall on Racial Justice during the 2020 virtual conference.

To recognize the exceptional work of those who are historically underrepresented in SECAC, higher education, and arts institutions, applications for the Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) awards, which cover the cost of conference registration plus two years of SECAC membership for five selected awardees, are due September 30. For details on the award, contact SECACaction@gmail.com or visit the SECAC Awards page.

CATALOGUE RAISONNÉ SCHOLARS ASSOCIATION (CRSA)

https://www.catalogueraisonne.org/

The CRSA has recently added a profile interview article on the Betye Saar Catalogue Raisonné Project (https://www.catalogueraisonne.org/profiles) as well as a new installment of personal responses from the art research and publication community on how they are managing during the pandemic (https://www.catalogueraisonne.org/ellipsis).

Historians of Netherlandish Art

The open-access, peer-reviewed, semi-annual Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art (jhna.org) encourages submissions on Netherlandish, German, and Franco-Flemish art and architecture (c. 1350-1750) and its global reach, including topics of interest surrounding colonialism, the slave trade, and the markets that supported them.

Renaissance Society of America

2021 RSA Research Fellowships

The Renaissance Society of America’s Research Fellowships competition is underway and submissions are due by 15 September 2020. We are awarding fellowships of $2,000 to scholars working in the field of Renaissance studies (1300–1700). The application site and details about the application process, eligibility, residential fellowship, non-residential fellowships, and publication subventions can be found here. Please email the RSA with questions.

FAQs for the 2021 Annual Conference

posted by CAA — Jul 16, 2020

We will update this page frequently. Thanks for your patience and flexibility!

This information is current as of September 10, 2020.

Why are we changing the conference format?

As we announced in our letter to CAA members, since the COVID-19 pandemic began, CAA’s prime consideration for planning the 2021 conference has been the health and safety of our membership and our communities. Even as parts of our world begin to “reopen,” we face many unknowns on what the state of health and safety will be in February.

We had hoped to convene a fully in-person conference in New York this February 10–13, 2021. However, the pandemic and uncertainty of the months ahead—as well as increasing economic pressures on institutions and individuals, leading to diminished funds for professional development and travel—have caused us to rethink our plans.

How did CAA come to this decision and why decide now?

Our decision was informed by a robust response (almost 1,200 replies!) to a survey sent to members in May regarding their ideas about CAA hosting an online conference. Exceptionally useful feedback was provided in terms of what types of activities would be appealing to attend online, the value of in-person gatherings, and what price points seem reasonable. We are building on what you shared with us.

There are many factors in determining the costs and benefits of going online; these are currently being evaluated by CAA staff and will continue to be addressed as we move forward. But making this decision now allows staff and the Annual Conference Committee time to plan for an iteration of the conference that will ensure the core benefits of the event are maintained: opportunities to share new research, listen to esteemed artists, designers, and scholars, and connect with peers.

What will the conference look like?

The program will include conference sessions online. We are also looking at ways to present other conference activities in person, depending on the state of the pandemic in early 2021.

After the Annual Conference Committee selects sessions to be included in the program, we will build a four-day conference with the same basic structure as the usual in-person conference, possibly with fewer sessions per day. We are also considering an extended schedule for sharing virtual sessions; the details of this will be determined in August, after the sessions are selected.

We are currently exploring options for other aspects of the conference (e.g., the Book and Trade Fair, Workshops, poster sessions, receptions) and will know more once the session content is scheduled.

We are taking into account the many concerns members have expressed about virtual presentations, such as sharing scholarship online, the challenges of different time zones, and “Zoom fatigue.”

Lastly, we will be surveying those whose sessions are accepted for the Annual Conference to understand technical and practical preferences for presenting their work so that we can address everyone’s particular needs and concerns.

We thank you for your patience as we address these issues. Please stay tuned for more details.

How has this affected the key dates for the conference?

Our submissions timeline was affected by the spring COVID-19 crisis and pushed back the overall planning process by roughly a month. The updated key dates are posted on the conference website and can be found at the bottom of the proposals page.

When will I know if my proposal has been accepted?

The Annual Conference Committee is currently reviewing the 800-plus proposal submissions and is on schedule to select those that will be included in the conference program. This process will be completed by mid– to late August and members whose submissions have been accepted will be notified.

Can I still submit a proposal/paper?

Yes. While the portal has closed for session submissions for CAA 2021, there are still ways to submit.

- Sessions inviting a call for participation (CFP) will be open from August 12 to September 16, 2020. A list of accepted sessions that are soliciting contributors and their abstracts will be posted at the beginning of August on the CAA website. VISIT HERE for more information. The chairs of accepted sessions that are soliciting contributors will accept proposals directly from submitters by September 23.

- Visit Call for Proposals for posters sessions and Workshops and related deadlines and participation requirements.

How will papers be delivered during CAA2021?

Session presenters will upload their prerecorded presentations, which conference registrants may access online shortly before and through the conference dates. Live Q&A will be scheduled for each session between February 10 and 13, providing the collegial, interactive, and accountable engagement created by attending sessions as a community. Questions about session presentations may be submitted to session chairs after viewing a session in advance of the scheduled live Q&A. Uploaded content will be accessible to registrants for a limited time after the conference dates. We will provide detailed information for presenters and attendees closer to the conference.

I have questions and concerns about presenting virtually and sharing my work. If I’m accepted, what can I do to prepare?

CAA and our technical support team will share guidelines for preparing for virtual sessions, including preconference webinars to walk both presenters and audience members through the technology of participation.

CAA’s Annual Conference Committee, legal counsel, and staff are working on protocols and guidelines regarding best practices to protect the intellectual property of participants. This information will be made available on the CAA website in early fall.

When will the conference website open and registration begin?

The Annual Conference website will go live in November 2020. At that time, you will see the session listings and details on other conference programming. You may also register for the conference at that time.

Will conference registration and fees change?

Registration options and fees will be posted in early November 2020. Information provided by the conference survey will help determine the fee structure.

In order to present at the Annual Conference, you must be a current CAA member and also registered for the conference.

What will be free and open to the public for CAA2021?

Programming by the Services to Artists Committee and the Student and Emerging Professionals Committee will be free and open to the public. A full list of free and open programming will be noted on the Annual Conference website when it opens in November 2020.

HAVE ANOTHER QUESTION?

For FAQs about Annual Conference Logistics, Submissions, Conference Registration, Membership, and Calls for Participation, VISIT HERE.

STILL HAVE A QUESTION?

We know we may not have answered all of your questions. Please let us know! Email questions to programs@collegeart.org.

We will update this page frequently. Thanks for your patience and flexibility!

Join a CAA Professional Committee

posted by CAA — Jun 15, 2020

Artist Jill Odegaard (left) and participant work on Woven Welcome as part of ARTexchange at the 2020 Annual Conference, an event organized by CAA’s Services to Artists Committee. Photo: Stacey Rupolo

Call for applicants to CAA’s Professional Committees (for term 2021-2024)

The Professional Committees address critical concerns of CAA’s members. Each Professional Committee works from a charge that is put in place by the Board of Directors. Committee members serve three-year terms, with the term of service beginning and ending at the CAA Annual Conference. Candidates must be current CAA members, or be so by the start of their committee term and possess expertise appropriate to the committee’s work. All committee members volunteer their services without compensation. It is expected that once appointed to a committee, a member will attend committee meetings (including an annual business meeting at the conference), participate actively in the work of the committee, and contribute expertise to defining the current and future work of the committee. For many CAA members, service on a Professional Committee becomes a way to develop professional relationships and community outside of one’s home institution, and to contribute in meaningful ways to the pressing professional issues of our moment.

The following Professional Committee are open for terms beginning in February 2021. Please click on the links in order to review the charge of each committee, as well as the roster of current committee leadership and members:

- Committee on Design

- Committee on Diversity Practices

- Committee on Intellectual Property

- Committee on Research and Scholarship

- Committee on Women in the Arts

- Education Committee

- International Committee

- Museum Committee

- Professional Practices Committee

- Services to Artists Committee

- Services to Historians of Visual Arts Committee

- Student and Emerging Professionals Committee

Committee applications are reviewed by the current committees, as well as CAA leadership (CAA’s President, the Vice President for Committees, and Executive Director). Appointments are made by late October, prior to the Annual Conference. New members are introduced to their committees during their respective business meetings at the Annual Conference in February 2021 in New York City.

In applying to serve on a committee, applicants commit to beginning a term in February 2021, provided that they are selected for committee service.

Prospective applicants may direct logistical questions to Vanessa Jalet (vjalet@collegeart.org). Questions about the committee charge and current work to the current committee chair and/or to the Vice President of Committees: Julia Sienkewicz (julia.a.sienkewicz@gmail.com)

Self-nominations should include a brief statement (no more than 150 words) describing your qualifications and experience, combined with an abbreviated CV (no more than 2–3 pages). These two items should be forwarded in a single PDF document emailed to: vjalet@collegeart.org

Deadline for applications: Monday, August 31, 2020

Kindly enter subject line in email: 2021 Professional Committee Applicant

An Interview with Suzanne Preston Blier on CAA’s Code of Best Practices and Publishing with Fair Use

posted by CAA — May 19, 2020

In 2019, Suzanne Preston Blier, professor of African art at Harvard University and former president of CAA, published a major book on Picasso’s use of global imagery, Picasso’s Demoiselles: The Untold Origins of a Modern Masterpiece. In addition to its scholarship the book is groundbreaking for its reliance on fair use, the principle within US copyright law that permits free reproduction of copyrighted images under certain conditions. CAA led the way among visual arts groups in calling for reliance on fair use, producing in 2015 its Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts.

In 2019, Suzanne Preston Blier, professor of African art at Harvard University and former president of CAA, published a major book on Picasso’s use of global imagery, Picasso’s Demoiselles: The Untold Origins of a Modern Masterpiece. In addition to its scholarship the book is groundbreaking for its reliance on fair use, the principle within US copyright law that permits free reproduction of copyrighted images under certain conditions. CAA led the way among visual arts groups in calling for reliance on fair use, producing in 2015 its Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts.

In this interview with Patricia Aufderheide, university professor and founding director of the Center for Media & Social Impact (CMSI) at American University, and a principal investigator in the CAA fair use project, Blier relates how she became an inadvertent pioneer of fair use in art history.

An Interview with Suzanne Preston Blier, Harvard University

By Patricia Aufderheide, American University

I met Prof. Blier, an award-winning art historian, when CMSI joined others in facilitating the Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts for the College Art Association (CAA), with funding from the Samuel H. Kress and Andrew W. Mellon Foundations. Fair use is the well-established US right to use copyrighted material for free, if you are using that material for a different purpose (such as academic analysis, for instance) and in amounts relevant to the new purpose. Blier was the incoming president, as the Code launched.

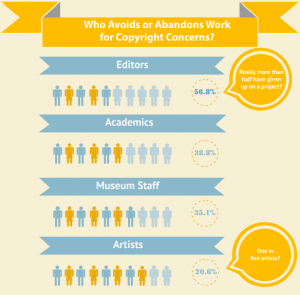

The project addressed a huge need. Art historians, visual artists, art journal and book editors, and museum staff all have faced major hurdles in accomplishing their work because of copyright. Art historians avoided contemporary art in favor of analyzing public domain material. Visual artists hesitated to undertake innovative projects that reuse existing cultural material. Editors, or sometimes their authors, faced monumental bills for permissions and sometimes those permissions depended on an artist or artist’s estate agreeing with what they say. Museums hesitated to do virtual tours, or use images in their informational brochures, or even to mount group exhibits, because of prohibitive permissions costs. All together, some people in the visual arts called this “permissions culture.”

Once the Code came out, some things changed immediately. Museums rewrote their copyright use policies. Artists made new work. CAA’s publications—some of the leading journals in the field—adopted fair use as a default choice.Yale University Press prepared new author guidelines for fair use of images in scholarly art monographs to encourage fair use. Blier was one of the Code’s champions.

And then she needed it herself. As she began work on her most recent book, which ultimately resulted in Picasso’s Demoiselles: The Untold Origins of a Modern Masterpiece (Duke University Press, 2019, winner of the 2020 Robert Motherwell Book prize for an outstanding publication in the history and criticism of modernism in the arts by the Dedalus Foundation), she realized the subject faced the stiffest possible copyright challenge. To tell her story, she would have to be able to show images from a variety of artists, most challengingly, Picasso. She thought of Duke University Press, a publisher that has been willing to go ahead of others on fair use. So Blier approached them. Duke was very supportive, and they ended up hiring extra legal counsel for this. In the end, Blier said, she had to rewrite certain sections, and redo some images at the suggestion of outside counsel, to strengthen the fair use argument.

Blier tells the story of how the book got out into the world (and won an award), below.

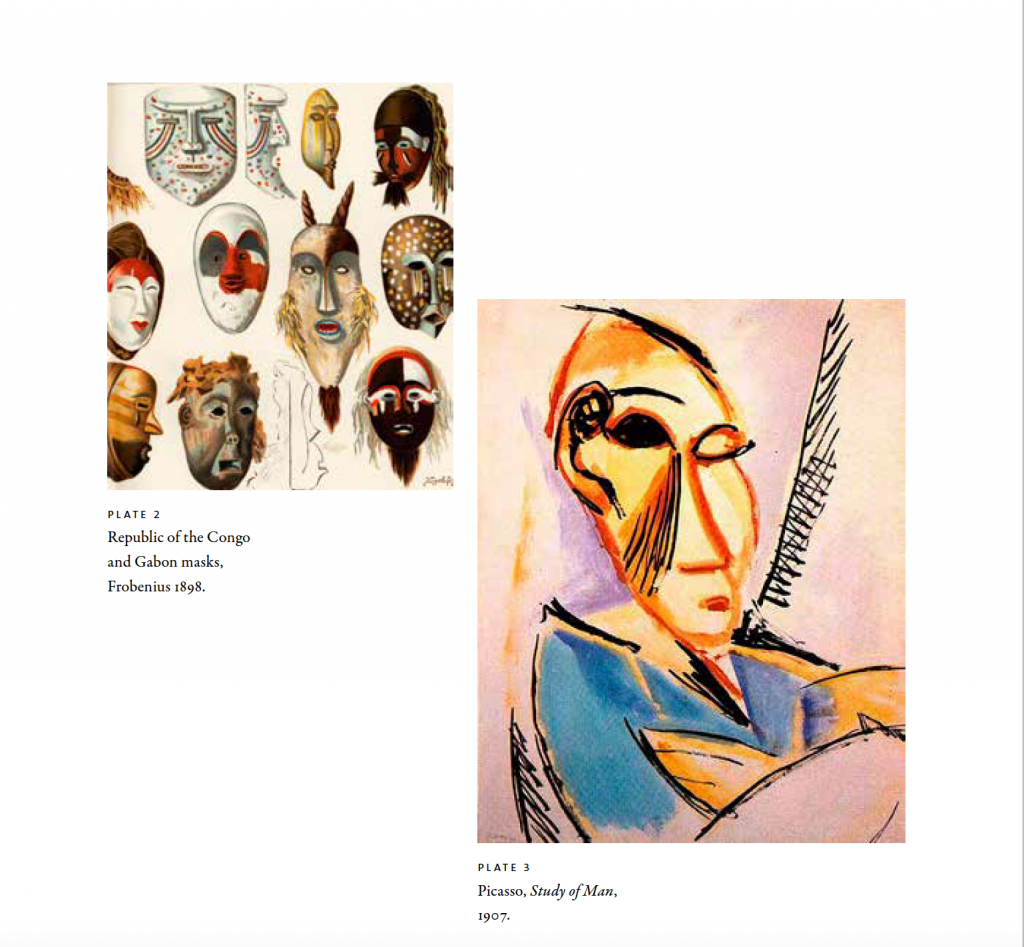

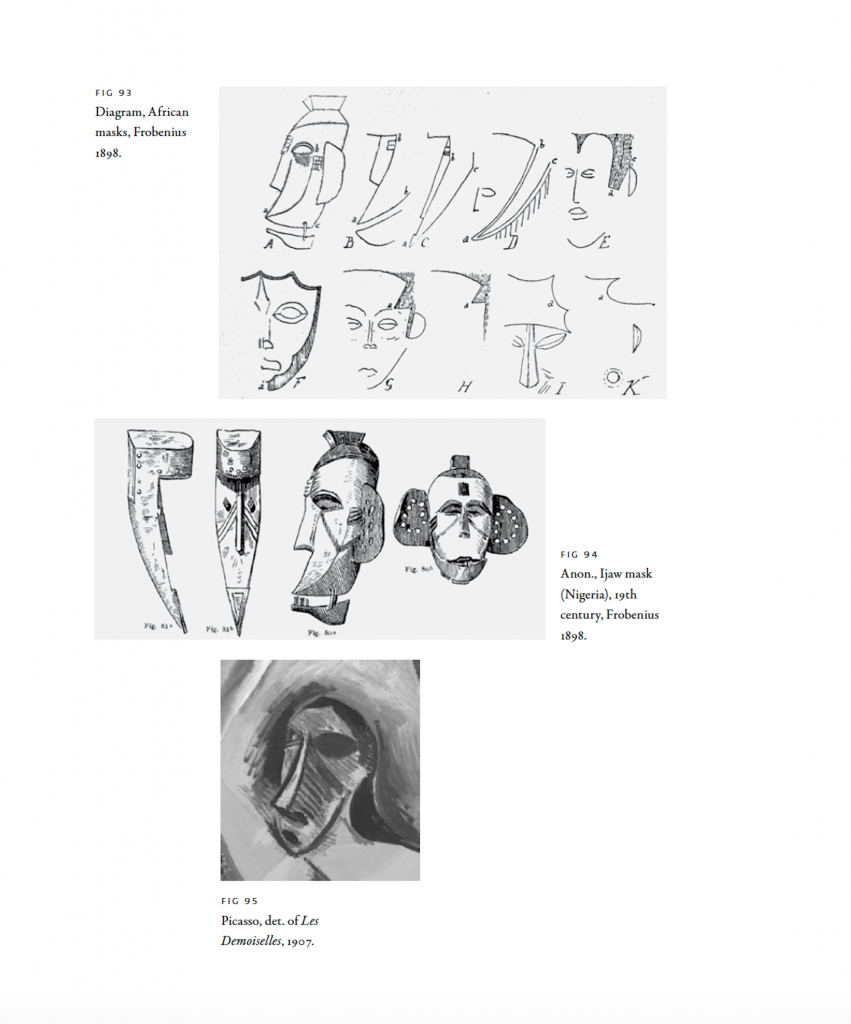

Figure 1. Congo masks published in Leo Frobenius’ 1898 Die Masken und Geheimbünde Afrikas alongside Pablo Picasso’s Study of Man (1907). The Congo mask at the bottom, second from the left is the likely source for the crouching demoiselle. The mask at the top left shows tear lines from the eyes crossing diagonally down the cheeks similar to Picasso’s preliminary study for one of the men in an early compositional drawings for the canvas.

You’re an expert in African art. How did you end up writing a book about one of the most famous modernist artists?

This is a book I never intended to write; it found me. For my previous book, Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba: Ife History, Power, and Identity, I was doing those last-minute bits of work in the library to check sources, and I pulled out a book adjacent to the book I was looking for, an old book by the German anthropologist, Leo Frobenius. I hadn’t read it since graduate school. As I opened it up, I looked down and I said, Wow, this is a book on African masks and they look like they’d be the ones Picasso used as models for his famous 1907 painting Demoiselles d’Avignon. At the time I had first read the book, Picasso’s drawings for the painting hadn’t been released. This time I saw it differently and as I was looking at it in the library, I saw there was tracing paper over the pictures. There was a line drawing covering each mask, and that seemed significant too.

The next thing I knew, I was hunting for a book from the Harvard library on Dahomey women warriors. It turned out it was in the medical school library, which should have been a sign. When I picked it up at the main library and flipped it open, I thought, Oh my god, it’s pornography! It was photos and line drawings of women around the world, in supposed “evolutionary” order. Photos of naked women begin with so-called “archaic,” in Papua New Guinea, right through to southern Europe, then Denmark. In the library I’m bending over, kind of hiding it, out of embarrassment. I bring it home and realize, Ohhhh! Here’s another key source for Demoiselles. This volume, which was by Karl Heinrich Stratz, had gone through multiple editions, and one was published about the same time Picasso stopped using living models. Then I found another book, by Richard Burton, which had a rendering that Picasso clearly used for his 1905 sketch Salomé.

What happened next was the clincher. I went to Paris to lecture at Collège de France. The week before my lectures, I went to hear another speaker at the Collège, a medieval historian. One of the first slides he presented was a work from a medieval illustrator, Villard De Honnecourt. This book was a modern edition of an illustrated medieval manuscript, published in the right time frame for Picasso to have seen it. And I thought, Well, here’s another source Picasso used.

Later I was also able to rediscover a photo that allowed me to date the painting to a single night in March 1907. The scene is often identified as a brothel, but bordel in French doesn’t mean bordello, but rather a chaotic or complex situation. It was my belief that Picasso was creating a time-machine kind of image of the mothers of five races, as he understood them from the Stratz ethno-pornography book and other sources, each depicted in the art style of that region or period. My larger argument is not only that Picasso was using book illustration sources, but also that these books invite us to see the canvas in a new light, and that, for Picasso, the painting has its intellectual grounding in colonial-era ideas about human and artistic evolution.

Figure 2. Illustrations from Leo Frobenius’ 1898 Die Masken und Geheimbünde Afrikas showing (top two rows) the visual development of a mask into a human face. The middle illustration ,from the same Frobenius book shows line drawings of ijaw masks from Nigeria. The bottom image is a detail of the standing African figure from Picasso’s 1907, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon which appears to be based on a combination of these two masks.

What a sleuthing job! And so you decided to write the book then?

I wrote the first two chapters while I was in Paris doing the lecture. I saw it not as a coffee-table art book, but the kind of book you put in your knapsack as you head off to a long ride on the subway.

It was easy to write, but it was a very different story for the images. I immediately got a trade publisher in Britain to agree to publish it, and then they said they could not do it, because of problems getting permission to reproduce images from the Picasso Foundation.

The Picasso Foundation is notorious for making it difficult to access Picasso images, isn’t it?

The price of permissions is high, and this Foundation like many estates is interested in guarding the artist’s reputation as well. The difficulties of publishing on Picasso have been manifested in how little publishing was being done, and how scarce the images were in that work. Since 1973, there have been few heavily illustrated books about Picasso, except by wealthy individuals or museums in relation to an exhibition. I had heard about Rosalind Krauss publishing a work without permissions—at least that’s what I heard—anyway, she used very few images. Leo Steinberg apparently had not been able to arrange the rights for a work he wanted to do, a book edition of his two seminal articles on Les Demoiselles.

Although I hadn’t realized it until recently, in September 2019 there was an important case in the US, about a set of illustrated books by Christian Zervos with a wide array of Picasso illustrations. The case was started in France, but a US judge has allowed fair use.

But generally, yes, there’s common wisdom among art historians that the Picasso Foundation is a formidable challenge.

So how did you proceed when the first publisher backed out?

I was disheartened, but I got an agent. He sent it off to ten or twelve trade publishers worldwide—and came up with nothing.

Then I realized I was going to have to go to a university press. That was a big decision. The trade publication will pay for the images, and do all the work on the rights clearance. But with a university press, you’re on your own.

One of the first people I contacted was legendary editor Ken Wissoker at Duke University Press. He was interested, but then came the issue of the images. I may have broached fair use with him from the start. The manuscript had gone through peer review and it was in great shape except for this copyright issue. I had quite a number of images—in the end, it was 338. At Duke, they won’t begin the editorial process until you have all the copyright clearances on images done. So I began the difficult process of deciding how to get the images.

Were you in contact with the Picasso Foundation directly?

I did contact them, in order to let them know about the project in general. I was doing final research work in Paris. I had framed the book as a travelogue in part addressing my discovery of these sources. I also wanted to find out so much more about Picasso. I’m not a modernist, I’m an outsider to the field. So I worked hard to get as much insight and criticism of the manuscript from specialists as I could.

I made it a point to meet with people at the Picasso Foundation. I had a Powerpoint of the images, which I showed to one of the key people there. Later I wrote to them, “here’s the manuscript, let me know if you have any thoughts.” And I heard nothing back. I had heard that with some manuscripts, they have been concerned one way or another. I didn’t want their permission for the intellectual content, but since they knew this artist and his life and family better than any academic could, I wanted their insights.

And then you started to look for permissions?

Well, I began to think about the cost of acquiring the images. The process is such that you have to go through the Artists Rights Society (ARS, a US licensing broker). And to get a price, you have to furnish the number of images, how many are color, the size of the print run, the prospective profit, and a whole series of things we could not know. Duke wouldn’t even look at the project editorially without having the rights in hand. I had heard difficult stories—that they were interested in looking at the galleys along the way, and requesting changes, for quality control, but it wasn’t possible to do this and work with the press.

If I had to guess, I would say that it might have cost me something like $80,000 of my own money to purchase the minimum number of images for this scholarly book, from which I expect to make no money, or very little.

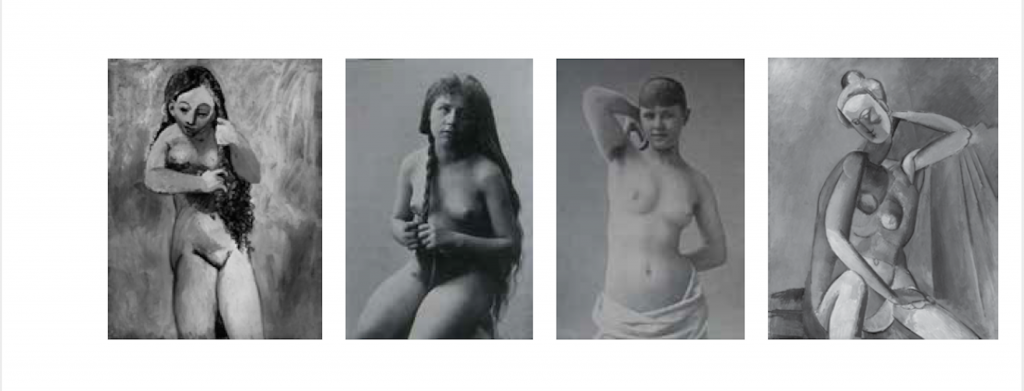

Figure 3 from left to right: Pablo Picasso, Nude Combing Her Hair, 1906; Girl braiding hair from C. H. Stratz, La beauté de la femme, 1900 (Paris); Girl from Vienna from C.H. Stratz, La beauté de la femme, 1900; Picasso Seated Female Nude, 1908. Over the course of his long career Picasso would continue to use key visual insights from Frobenius, Stratz, and other illustrated sources he was exploring in this late 1906 to early 1907 period.

So how did you come to the decision to use them under fair use?

I had been president of CAA in 2016-17, and a longtime promoter of fair use and IP issues more generally. I was involved in the creation of the Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts. For me, CAA’s role in fair use is one of the most important and radical (in a positive way) things that it has ever done.

I decided that fair use would make the most sense in this context. This was a book about an important modern artist. In addition, I’m a senior scholar—this was not my first publication. If the worst happened, if I had problems, well, I’ve had a great career and this would not harm it. I have tenure and so on. Also, as the then-president of CAA, I thought it was important to do this.

Besides, this to me was part of a larger picture of what I had done in my larger career. I’m very active locally in civic affairs, and really interested in promoting transparency, and democratic ideals. I was also very fortunate to have Peter Jaszi, a foremost legal scholar on fair use (and another principal investigator on the CAA project), working with me. At his suggestion, I took out an insurance policy, which for a fee—I think about $5,000—(with a $10,000 deductible) I was able to lower my anxiety level. I also paid $400 for an attorney to look over the insurance contract. And I had good friends like you, who when I got cold feet assured me it was the right thing to do. And of course, Duke is a publisher that has been willing to go ahead of others on fair use.

Can you give me an example of something you had to change in the text to strengthen the fair use argument?

With a museum photograph of an African mask, for example, I had to explain why this particular way of photographing the work was critical to the argument in my book. I had to ad a few sentences to justify my selection of several Picasso works as well. I also had to give reasons in my text for why each of the chapter epigraphs was necessary.

Did you have to alter the use of imagery in any way to accommodate fair use?

There are changes the press made, design-wise, that reflected in part the decision to employ fair use. Many of the photos are shown in black-and-white and the majority are reduced in size. I was constrained by the fact that I could only employ fair use if I could get access to the materials without going through the Picasso Foundation. So I had to acquire nearly all the images from published books, and many of the Picasso images were published in black and white and at a very small size, in a grainy context. I had to spend a lot of time hunting down the best possible images to use. In my book they are shown in relatively small size, along with information on where you can find color versions online.

That didn’t bother me too much, though. For readers and viewers at this juncture in the Internet era, we have become expert at extrapolating the fuller figure from a small image.

There is also a small spread of color images, a couple Picasso works as well as from other artists. For these images color was central to the book.

The decision to publish largely in black-and-white was, I think, also related to the fact that the Picasso Foundation and others are concerned that color representations be incredibly accurate, and it is very hard to get the color exactly right, when copying from books. You also have an issue with paper quality in getting accurate representation.

The cover is a handsome design, and very clever. They broke up the images into thumbnail-like sections, requiring you as a viewer to put them together as one image, similar to how Picasso was thinking in the early stages of cubism, where you as a viewer of an assemblage have to assemble them in your own mind, to make it work for you as a whole.

How was the book received?

It was a finalist for the Prose Prize, a prize of publishers to authors. My previous book won it in 2016. I didn’t expect to win it this time again, in 2019. I was very honored that it was a finalist. It was also featured in the Wall Street Journal’s holiday art book list. And then, just recently, it won the Robert Motherwell Book Award.

Has the Picasso Foundation seen the book?

To date I’ve heard nothing. I was thinking earlier that the Picasso Foundation might want to stop it pre-publication. So much so that when I came back from travel in Africa, I went first to my academic mailbox, and was relieved when I saw no big legal envelope. But there has been no pushback. I certainly gave them the opportunity to comment on the content while it was still in manuscript. And last April or May, I went to France to meet with the curators at Musée Picasso about contributing an essay to a catalog. I sent them an article draft which they decided not to publish, which is fine, but also sent them a copy of the manuscript, and of course the Musée speaks to the Foundation.

Interestingly, the two cases where the Foundation has sued or prevented publication that I know of have to do with children’s books about Picasso. I don’t know what that means.

Does the wider art history community know about this?

I hope this personal story makes a difference. We still have a lot of educating to do, in spite of the work we did around the Code. I continually get, on the art history listservs, questions—How can I get permission, and I always say, Use fair use. People still don’t trust it or believe it’s more difficult than it is.

At the CAA conference I just went to in Chicago, there seems to be a division between presses. Presses at private universities–Yale, Princeton, MIT, Duke—seem to feel more comfortable exploring this. But for university presses at some public institutions, these legal issues have to be taken up with the state attorney general, and there can be real nervousness stepping outside a narrow parameter. I learned this speaking to an editor at a state university press in a progressive state, who believes they’re being held back because of this fear.

I was pleased to see at this same conference a pamphlet on fair use by Duke University Press’s former Director, Steve Cohn. In his essay, he mentions my Picasso book and how happy he is that Duke chose to publish it this way. I figured, if Steve is openly talking about this fair use project, then the proverbial cat is out of the bag, and I could be more open and provide some of the back story from my end.

CAA’s scholarly publications, The Art Bulletin, Art Journal, and Art Journal Open rely on fair use as a matter of policy, and indicate when they do so in their photo credits. View a complete discussion of fair use and CAA’s Code of Best Practices.

Announcing the 2020 Recipients of the Art History Fund for Travel to Special Exhibitions

posted by CAA — May 12, 2020

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

In fall 2018, we announced CAA had received an anonymous gift of $1 million to fund travel for art history faculty and their students to special exhibitions related to their classwork. The generous gift established the Art History Fund for Travel to Special Exhibitions.

The jury for the Art History Fund for Travel to Special Exhibitions has now selected the second group of recipients as part of the gift. This year’s awardees are:

Holly Flora, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA

Course: Art, Cosmopolitanism, and Intellectual Culture in the Middle Ages

Exhibition: Medieval Bologna: Art for a University City at the Frist Center for the Visual Arts, Nashville, TN

Caroline Fowler, Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA

Course: Slavery and the Dutch Golden Age

Exhibition: Slavery at the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Maile Hutterer, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR

Course: Time in Medieval Art and Architecture

Exhibition: Transcending Time: The Medieval Book of Hours at The Getty Center, Los Angeles, CA

Erin McCutcheon, Lycoming College, Williamsport, PA

Course: Art & Politics in Latin America

Exhibition: Rafael Lozano-Hemmer: Unstable Presence at SFMOMA, San Francisco, CA

Shalon Parker, Gonzaga University, Spokane, WA

Course: Women Artists

Exhibition: New Time: Art and Feminisms in the 21st Century at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, Berkeley, CA

Rebecca Pelchar, SUNY Adirondack, Queensbury, NY

Course: Introduction to Museum Studies

Exhibition: Marcel Duchamp: The Barbara and Aaron Levine Collection at the Hirshhorn Museum, Washington, DC

As museums and schools have moved online in light of the coronavirus pandemic, we are being as flexible as necessary with the dates of travel to accommodate all award winners and classes.

The Art History Fund for Travel to Special Exhibitions supports travel, lodging, and research efforts by art history students and faculty in conjunction with special museum exhibitions in the United States and throughout the world. Awards are made exclusively to support travel to exhibitions that directly correspond to the class content, and exhibitions on all artists, periods, and areas of art history are eligible.

Applications for the third round of grants will be accepted by CAA beginning in fall 2020. Deadlines and details can be found on the Travel Grants page.